|

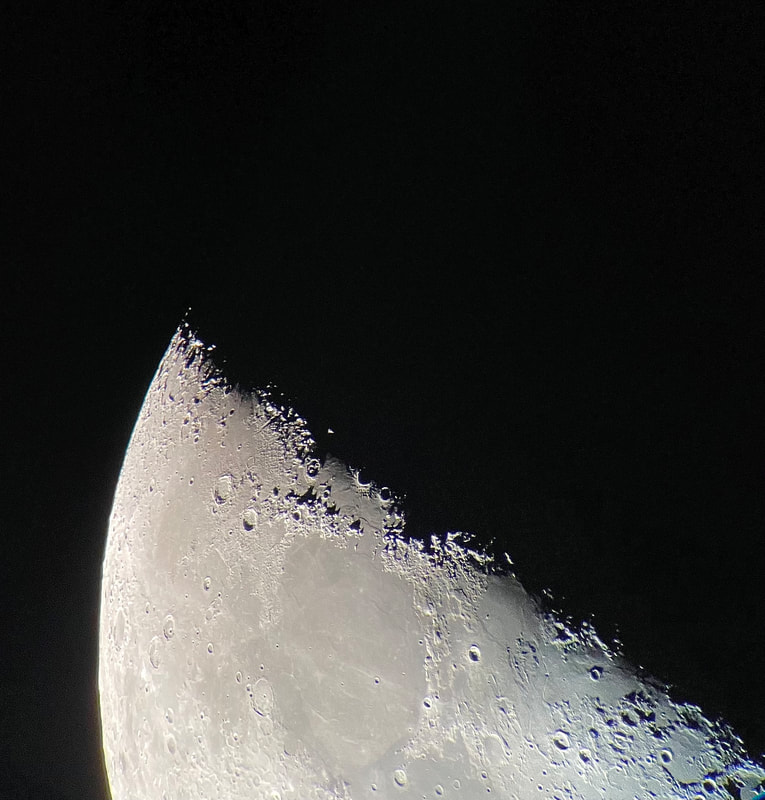

You have to strike while the iron is hot here in DC, so when the sky was clear again last night, with seeing and transparency both forecast to be average, I shrugged off my late night fatigue and trudged outside, Takahashi in hand. I didn't have it in me to walk all the way to the park, so I walked over to the (much closer) church. Unfortunately the bushes that once shielded me have been trimmed, so it's now impossible to avoid the white glare of nearby streetlights. That stops my eyes from fully adjusting to the dark - which means that, when I'm at the church, deep space objects (other than double stars) are out of reach. Luckily the waxing Moon was high in the sky. Once glance at the Moon - and the Capitol Dome shimmering downhill - confirmed that seeing would be quite good tonight. I used my Berlebach Report tripod, which can just handle the FC-100DZ on either my AYO II mount, or the DiscMounts DM-4 that I recently acquired. The bigger Uni tripod is definitely much sturdier - I used it last time in better seeing - but heavy enough that I didn't want to bring it out tonight. Once again, my first glimpse of the Moon was a little disappointing tonight. Yet after a few minutes, the telescope and my eyepieces cooled down, and everything snapped into focus. If you ask me, the Moon is at its best when (roughly) half illuminated, especially the northern hemisphere. As I've written here before, I get a real kick out of following how the appearance of the crater Plato changes with the coming and going of lunar day; those changes became a fixation for nineteenth-century Selenographers hoping to detect evidence for volcanism - or perhaps life - on the Moon. Tonight I thought I could just about make out a few craterlets in Plato: a classic test for good seeing (and good optics). Further south, the huge crater Copernicus is also a pleasure when the terminator is nearby. As Air Force and Army lunar mapping projects competed with one another in 1959, Patricia Marie Mitchell Bridges labored in secret to sketch the crater - and create the finest representation of a lunar environment produced to that point. Thereafter, Air Force maps would pave the way for NASA's expeditions to the Moon. If you ask me, the human history of this corner of the Moon is among the strangest - and richest.

For me, the view tonight was not quite as crisp and clear as it was on the 20th. Still, the Takahashi acquitted itself well, despite the relatively wobbly mount. After about 40 minutes I hit the wall and packed up, exhausted but satisfied.

0 Comments

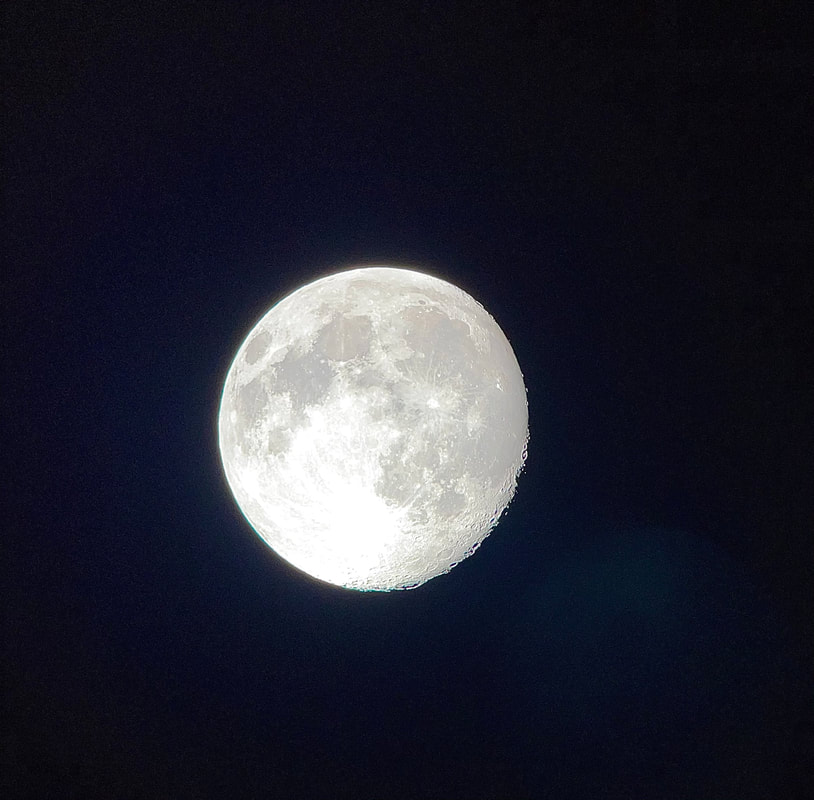

It seems that the cloudy, turbulent days of winter - in more ways than one - are finally coming to an end. In the wee hours of March 20th, the sky was clear, transparency was (supposed to be) high, and seeing was about average. Conditions, in other words, were about as good as we've had in months. I trotted out with my EVScope, intent on imaging some of the deep space wonders that are now prominent in the early modern sky. After a lightning-quick setup, as usual, I directed my attention to M51, the Whirlpool Galaxy, which is colliding with (and ripping apart) NGC 5195, a smaller galaxy. After a seven-minute exposure, the results impressed me - and for once I noticed that the image looked better when I peered through the eyepiece. Two other galaxies beckoned around the same constellation (Ursa Major, or the Big Dipper): Bode's Galaxy (M81) and the Pinwheel Galaxy (M101). Both are much trickier targets. Bode's bright core is easy to find, but its spiral arms are easily lost; the Pinwheel is big, but has generally low surface brightness. While transparency was supposed to be high, the sky was actually remarkably bright, and I noticed clear halos around street lamps. If anything conditions promised to be poor for both galaxies, and sure enough I wasn't pleased with the results. Here's a three-minute exposure of the Pinwheel Galaxy; you'll see it doesn't exactly impress. That's the thing with the EVScope, and something I haven't seen mentioned in any review: like all telescopes, it performs much better under a dark sky. While there's a lot of hype about how it will reveal deep space objects in the middle of the city, that promise holds up much better for objects that are already bright. Fainter objects can be lost in the glare of light pollution, just as they are in traditional optical telescopes. I'll try these galaxies again when conditions are better, but I don't expect radically different results. By the evening of the 20th conditions had improved dramatically. Both seeing and transparency were now good: a confluence we haven't had here in DC since November, maybe October. Although I was exhausted from waking up early on the previous night, I had to walk out with my Takahashi to catch the Moon while it was still quite high in the sky. As I've written, I've been a little disappointed since swapping my FC-100DC for the DZ, which is supposed to offer slightly better color correction. While I had only used it in nights of bad seeing, I was beginning to worry that it might have been knocked out of collimation in transport. After I set up on the night of the 20th and glanced at the Moon, those worries only grew: the image looks distressingly soft, and I started thinking about how to contact Takahashi. Yet after a few minutes the telescope cooled down, and then: wow. Suddenly the Moon snapped into crystal clear, razor-sharp focus, with absolutely zero false color anywhere - including along the lunar limb, where the slightest undulations and shadows were totally crisp. No matter which eyepiece I used, the detail was spectacular. What stood out the most? Probably the rilles; they seemed to be everywhere, and so delicate that they looked like veins on a living thing. After a little while I concluded that the view seemed best with my 6mm Delos at 133x. At that magnification I could still see the entire Moon, but I was close enough to make out truly breathtaking detail, in every conceivable shape and form. It truly felt as though I was looking out the window of a spaceship, approaching the Moon after a long journey from Earth. There are times when the atmosphere cooperates, and something spectacular is in the night sky, that it doesn't take long for me to have my fill; to feel as though I can't take in any more, because I just want to savor and remember what I've seen. So it was this night. After about 40 minutes, I packed up and walked home. So yes, the FC-100DZ is an extraordinary telescope. To me, it has a bit less false color than the DC and significantly less than the TV-85, although both of those telescopes really had very little, and that gives it a small edge in sharpness. The difference is subtle but noticeable - on nights of good seeing. Of course, those night don't come along very often, and I've found that on most clear nights the state of the atmosphere matters far more than slight improvements in instrumentation. The FC-100DZ's bigger improvement over the DC, as I've written, is probably its modest but meaningful mechanical upgrades. Still, owing fine refractors has made me a little obsessive about the details, and for me the move from a DC to a DZ appears to have been worth it. That's a relief! I've written it before, but wow: Washington, DC is such a feast or famine city for amateur astronomy. We've had bad seeing on just about every clear night (and there haven't been many) for around five months now. At last, this month, the clouds parted - but on night after night, the seeing remained poor at best. I took out the Takahashi FC-100DZ twice, and both times found the seeing well below average. Both times the Moon failed to impress as it otherwise might, and stars shimmered and danced in the eyepiece. Mars had long since set; I won't have another good look at the planet until 2022. At last, at 4:30 AM on Wednesday morning I stepped out with my EVScope and found the seeing to be . . . okay? It was windy near the ground, to my great frustration, but the stars scarcely twinkled and the internet confirmed it: seeing, it seemed, was about average. Of course that doesn't matter as much as transparency when you want to observe most deep space objects, but transparency was average, too. The sky, in other words, was about as good as it's gotten since autumn. It was a little cold, however, and muddy where I set up in the park. I hoped to test the EVscope on the Ring Nebula and the Hercules cluster: two objects I admired last year with my refractors. The scope aligned itself within seconds - why can't other mounts do this? - and I soon found it to be in perfect collimation. Moments later, it had found the Ring Nebula and I began a short exposure. As I wrote last year, under urban skies the Ring Nebula looks like a ghostly grey ring with a fine four-inch refractor - a ring you can just, just make out with direct vision. Using the APM 140 with averted vision, the ring was plainly obvious. In darker skies, with a four-inch Takahashi, the ring was equally obvious and appeared a little flattened. Every time I looked, there was a visceral thrill to seeing it, with just a couple lenses between my eye and the nebula. Yet through the eyepiece, the object itself was a subtle pleasure. The experience couldn't be more different with the EVScope. That thrill of seeing something with your own eyes is just about gone. Unlike others, I really don't like looking through the scope's eyepiece; it's like looking down a barrel, for one, and at the bottom of that barrel it's clear that you're seeing a screen. Maybe I've been spoiled by fine refractors and fine eyepieces, but it's a letdown. So I look at my phone, and for the most part I wait. The experience of observing - of learning how to see - is completely lost with the EVScope. Yet the thrill of seeing deep space objects otherwise barely visible from the city beginning to resemble their true selves is simply something you can't get with a traditional telescope under an urban sky. This time I really was floored when the nebula almost immediately turned green on my screen, and then when its perimeter began to seem orange, and then when its interior started to take on a greenish hue. The breeze pushed on the tube just enough to blur some of the stars, but what a wonder. Observing the Hercules cluster was a slightly different story. The cluster is always a highlight for me, not least because it's three times older than Earth - or because we beamed a message there from Arecibo, in 1974. With one of my refractors, it looks like a smudge at first from downtown DC, but after a while the stars come out, like diamond dust on a velvet background. It's subtle - exceptionally so with one of my smaller scopes - but magical nonetheless.

Again, the experience couldn't be more different with the EVScope. Hundreds of stars are easily visible, but of course they're slightly bloated; they lack that crushed gemstone beauty that you get with a fine refractor. Many of the stars are also clearly red, a testament to their age: again, things are visible through the EVScope that just aren't accessible with a regular telescope. Is the view more impressive? Maybe not to an experienced observer, but it's different, and that's a good thing. Some complain that the EVScope delivers the same experience you might get with a much cheaper (and more unwieldy) astrophotography setup. That's just not true. The EVScope is marvelously portable, and I can set it up in about one minute. It needs virtually no time to cool down. It's a joy to use and on most nights there's no fuss at all. In half an hour I can pack up - this takes another minute - having observed at least three deep space wonders as I otherwise never could. The key point is that the EVScope delivers a fundamentally different experience than you'd get with either a traditional telescope or an astrophotography setup - and again, I view that as a very good thing. |

Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed