|

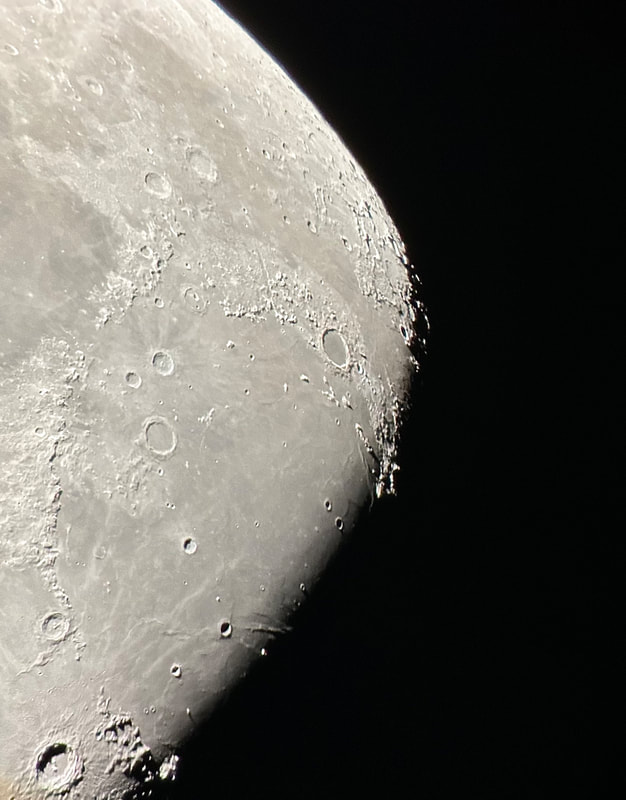

Our indefatigable news media seems to have transformed every full Moon into a show-stopping event. It's always a super blue wolf harvest something or other. To be fair, the hype stirs up a good deal of popular interest in our neighboring world, and to my mind that can only be a good thing. Of course, amateur astronomers know that because a full Moon has no shadows, it can be unsatisfying to observe with a telescope. The craters, mountains, and rilles that are otherwise so obvious seem washed out in a sea of milky-white brilliance. Still, the trees in my backyard have not yet unfurled their budding leaves, and pockets of the night sky remain visible just steps from my kitchen. The other night, I couldn't resist setting up my Takahashi TSA 120 as the full Moon moved through a gap in the bare branches. Atmospheric transparency and seeing were both about average - at least in theory. In practice, conditions seemed to shift by the minute. Occasionally a watercolor softness blurred the Moon, but then it snapped into focus for many seconds at a time. For amateur astronomers, our atmosphere truly is a fickle antagonist. Using my iPhone, I don't believe I managed to get a picture of the Moon in its clearest moments. Still, just look at those mountains outlined in sharp relief on the limb of the Moon. Rarely have I managed to get such an obvious look at them. Crater rays, meanwhile, are actually a lunar feature that becomes obvious only with the Moon fully illuminated. It was wonderful to follow their tendrils across the the Moon's silvery regolith. As for the telescope, what is there to say? Among apochromatic refractors, the TSA 120 is about as perfect as it gets. Nitpicking comes easy to me, but in this case there are no nits to pick. Actually, the telescope's size reminds me a little of the Vixen ED115S that I used to own (with its oversized Moonlite focuser). I thought the Vixen was the perfect size for a refractor, but the TSA might be even better. It actually feels a bit lighter and more compact, but the aperture is just a bit bigger. A five-inch refractor is a really ideal: it edges out the performance of a four-inch, but doesn't need a much bigger mount and tripod (which can be necessary with just half an inch of extra aperture). I recently acquired a DSV3 mount from Desert Sky Astro. This is a manual mount that isn't too heavy and seems extremely well made. It includes both slow-motion controls and a handy "quick balancing system" that allows you to easily compensate for the weight of different eyepieces. With just a flick of the wrist, the telescope stays balanced. It's a clever little feature that, I discovered last night, makes observing just that much easier.

Readers will know that I'm a manual mount aficionado. When you don't have much time to observe, or if you want to avoid all hassle in a public park, there's simply nothing better. So far the DSV3 seems like the best medium mount I've used, and I've tried just about all of them. It's at least as well made as the best mounts on the market, and it includes features that its competitors simply don't offer. For the TSA 120, it truly is just about perfect. After I'd observed for no more than 30 minutes, the Moon rolled behind my building, and with fingers numb from cold I packed up my telescope. As I've mentioned here before, it's hard to think of a better use of time than exploring another world from the comfort of your backyard.

0 Comments

Electronically Assisted Astronomy (EAA) has been around for a while. Not long ago, you'd get into it by buying a camera, attaching it to your eyepiece, hooking it to a monitor, and then watching as it combined - or "stacked" - images of nebulae or galaxies. Before long, the image on the monitor would take on the recognizable shape and color of a deep space object that, viewed unaided through the eyepiece, appeared as little more than a barely-perceptible smudge. Gone was the romance of peering at the space beside that smudge (using averted vision) and imagining, say, the combined light of 250 billion stars. But, if we're being honest, the magic got a little stale when squinting at one equally dim blob after another. EAA offered no substitute for looking through a big Dobsonian under a dark sky. Its images paled in comparison to those that could be taken with a complicated astrophotography rig. But for those of us stuck in the city and unwilling or unable to try serious astrophotography, EAA let us see what otherwise seemed out of reach: the universe beyond our solar system. A few years ago, two startups - Unistellar and Vaonis - took the obvious next step by debuting an integrated telescope, go-to mount, tripod, and stacking camera. Both the EVScope (Unistellar) and Stellina (Vaonis) were small, portable, and remarkably easy to use compared to any telescope on the market. Both were priced far beyond the cost of their parts; it is, after all, expensive to sell a niche product as a brand-new company. Still, despite the exorbitant cost - I shudder to think of what I paid for my EVScopes - enough people bought the new "smart" telescopes that both companies seem to have prospered. When both the EVScope and Stellina succeeded, it was clear that amateur astronomy would never be quite the same. The technology would keep improving, and bigger, more established companies would get in the game. A maturing market, meanwhile, would permit economies of scale. Those who waited on getting the first-generation EVScope or Stellina reasoned - correctly - that prices would soon collapse. Anyway, I bought my EVScope 2 for about $5,000. Recently, Vaonis released its next-generation Vespera II for about $1,600. The Vespera II is much more compact, it has a more sensitive sensor, it focuses itself (unlike the EVScope), and it's built around an apochromatic refractor that, in theory, should yield sharper images. I sold my EVScope and used the funds to purchase the new Vespera - and a few other things, because wow that price difference is huge. These are two approximately 10-minute exposures of the Orion Nebula. Atmospheric transparency and seeing were about average - maybe a little worse than average - while I took the picture on the left. Both conditions were definitely above average while I captured the shot on the right. Believe it or not, Orion was also much higher in the night sky while I took the picture on the right than when I took the image on the left. Of course, I took the picture on the left with the $1590 Vespera II and its $229 light pollution filter, while I took the image on the right with the EVScope 2, which is now on sale for $4,409. The Vespera focuses itself, but I'd carefully collimated the EVScope before using. I expected a difference in performance, sure, but the magnitude of that difference still astonished me. Actually, these pictures do not reveal the biggest distinction between the two images. Because of the Vespera's shorter focal length and more sensitive sensor, its images capture far more of the night sky. In fact, its new "CovalENS" feature allows for the integration of multiple stacked images of adjacent corners of the night sky, which should enable sweeping mosaics of, say, the entire Andromeda Galaxy. And I should emphasize again that the Vespera is much smaller and more portable than the EVScope. Admittedly, the EVScope comes with a tripod, while the Vespera does not (though again, the Unistellar backpack is much pricier than the one offered by Vespera). And the EVScope does have other advantages over the Vespera. It has an eyepiece, so if you want to use it like a regular telescope, you can. As I've often reported in these pages, the view through the EVScope eyepiece looks better than the pictures, though I suspect this is partly because the image is smaller. Magnifying the image on the bigger screen of a phone - let alone an iPad or laptop - reveals its imperfections. The Vespera also looks like something built by Apple, seemingly to appeal to buyers who see Apple as the gold standard for sophisticated, problem-free technology. It's a problem. The telescope's sleek surface is slippery and difficult to handle, especially in the cold. Screwing it into or out of a tripod is frightening. It wobbles dangerously and threatens to plummet to the ground (not a problem with the EVScope). It's also easy to accidentally open the Vespera, since there's nothing to lock the optical tube in place until needed, and the power button is far too easy to activate while holding the telescope. The button shines with a bright blue light when it's on. That will be familiar to users of common consumer products, but any amateur astronomer will tell you that a bright blue light is exactly what you don't want as your eyes adjust to the dark. Unlike the EVScope and other competitors now on the market, in important ways the Vespera prioritizes form over function. There's more. Whereas the EVScope has no problem with nearby street lights, the Vespera's lack of a dew shield allows those lights to easily create distortions in the image. Horizontal lines at the top corner of my images, I was told, are the product of a nearby (but not particularly bright) light. The lack of a dew shield is also, of course, a ticket to frustration in cold or humid climates (Washington, DC can be both). Vespera sells a screw-in Hygrometer Sensor - for an extra $119.

Then there's the lack of citizen science. Unlike Unistellar, Vespera has no fancy partnerships with the big guns in space science. If you want to join my friends at the SETI Institute in searching for exoplanets, you're out of luck. And if you want to help NASA track its spacecraft, stick to the EVScope. The biggest problem with the Vespera II, however, is battery life. The EVScope 2 can keep imaging for up to nine hours, and other Unistellar models do even better. By contrast, the Vespera has four hours of battery life - supposedly. I found that its battery consistently dropped down to 85% capacity after I had set it up, which takes over five minutes (setup was much quicker with the EVScope 2). In subzero temperatures, I suspect I could squeeze about three hours out of the telescope. Storage capacity is also much lower in the Vespera II, compared to the EVScope 2, but to me that doesn't matter; I always move good pictures to my phone's photo album. So do the many little shortcomings of the Vespera II, relative to the EVScope 2, overwhelm the advantages of its sharper, bigger, more colorful images, its autofocusing, and its more portable size and weight? The answer is: no, not even close. At present I think the new Vespera is simply a much more capable telescope, and again: it's sold at a fraction of the cost. In fact, I now fear for the future of Unistellar. The likes of Celestron and ZWO are offering telescopes that target both the high and low ends of the smart telescope market. I suspect that, if Unistellar stays in business, it will owe a lot to the connections its founders wisely made with SETI and NASA. I should say that I've reached my conclusions primarily by observing the Orion Nebulae. Planetary images, I suspect, are better with the EVScope 2 than the Vespera II, owing in part to the former's greater focal length and aperture. But that's really not why I'd want to use EAA. Even my C90, for example, gives a vastly better view of Jupiter than the EVScope could provide at twenty times the cost. Of course, as I've often described in these pages, all smart telescopes have the same shortcoming. To use them you wait around and stare at a screen. There's still something different - something special - about looking through a glass eyepiece instead, at age-old light at it shimmers through our roiling atmosphere. Usually, the atmosphere is turbulent during our DC winters, but this winter has been an exception. The reason might have to do with atmospheric circulation rerouted by a particularly intense El Niño, but I'm not sure. In any case, winter has been unusually accommodating for amateur astronomy in the District. Yet I haven't taken out my telescopes, and I haven't updated this blog, because, unfortunately, I've found myself too sick, too overworked, or - most often - both. This month has been much better, however, and on the 18th I finally decided to give my kids a view of the halfway-illuminated Moon. I stepped out with what is now my smallest refractor - the Takahashi FC-100DZ - and quickly found atmospheric turbulence to be a little worse than average. That's perfectly okay for a DC winter, and after the telescope cooled down - in about ten minutes - it delivered a very nice view of the Moon. Unfortunately, when uploaded to this blog the picture looks a bit blurrier than it does on my desktop. But look closely at the center. That's Rupes Recta, a linear fault about two kilometers wide that cuts across some 110 kilometers of the lunar surface. Here it is zoomed in: Just below the fault are the craters Birt A and B, named after William Radcliff Birt, a nineteenth-century selenographer. Birt coordinated a network of amateur lunar observers across Britain who all sought to record changes in lunar features, which they thought would reveal the Moon to be a world similar to Earth. It's a story that I'll describe in my next book, Ripples on the Cosmic Ocean. The book is one reason I've been so busy this winter: I've finished a complete draft, and am now revising (partly by shortening). In any case, the kids enjoyed the Moon. For them, it's a neat little thing that daddy likes to show off occasionally. Of course, I try to impress them by waxing poetic about the wonder of gazing, from a comfortable little backyard, at the alien peaks and hollows of a whole other world, one utterly different from our own. They're appreciative, but hardly awestruck. I've decided that it's nice that Moongazing is so normal for them. The following night was clear again, but a good deal colder. Still, I decided to try my Mewlon 210. After letting it acclimate for about 90 minutes, I walked over to a nearby tennis court and pointed it at the Moon. Once again, I was struck by just how easy the Mewlon is to handle. It's lightweight, and you hold it by the rock-solid finder scope. It's just a wonderfully-crafted hunk of metal and glass. It's hard not to want to use it, if that makes sense. When I pointed the Mewlon at the Moon - and yes it's so nice not to have to attach and then align the finder scope - I found it was cooled down and well-collimated. Atmospheric seeing was about average, but the view was quite breathtaking. The terminator had advanced a little beyond my favorite spot on the Moon - the expanse between and around Plato and Copernicus - yet both craters retained a hint of shadow around their rims. The Mewlon gave a three-dimensional quality to the extraordinary complexity of the terrain in this part of the Moon, in particular the mountains and crater rims. The iPhone pictures I took suggest some off-center coma distortion, but I noticed nothing while viewing the Moon. I don't know what to make of that. Still, I can report that I stepped inside - hands nearly frozen - thinking that I'd be crazy to ever sell my Mewlon. On the following night - that's the 20th - I sat down to write this blog entry. Then I noticed the Moon, shining through my window. I checked and, lo and behold, seeing was supposed to be better than average - way better than I normally expect in winter. I hesitated, but of course the temptation was too strong. I stepped out with the DZ, because I needed something that cooled down fast. This time the view was truly sublime. With the Moon near zenith and the atmosphere unusually stable, the fully-acclimated DZ showed off what it can do. The view wasn't as bright as the Mewlon offered on the previous night, but owing to the steady atmosphere they were a bit more detailed. I noticed craterlets on Plato's floor with the Mewlon - a classic test of good seeing and optics - but now, with the DZ, they were more continuously obvious.

I soaked in the view for a 30, maybe 45 minutes as my fingers slowly froze. I did notice that the view routinely slipped ever so slightly out of focus, owing perhaps to the focuser with the telescope pointed straight up. But wow, that in-focus view was wonderful: among the best I've had of the Moon. I especially enjoyed the lunar maria. The picture above gives a hint of the delicate tendrils I followed across those maria: subtly different shadings, some radiating from brilliant, intricately-detailed craters. It was a lot to take in, but my fingers soon convinced me to pack up and head inside. Lunar observing is perhaps overlooked in amateur astronomy, but it truly is an incomparable experience to explore another world while standing within sight of home. If November isn't my favorite month to observe here in Washington, DC, it's right up there with March and April. Most nights are cool, crisp, and imbued with an ineffable fragrance - of decaying leaves in autumn, of budding blossoms in spring - that encourages deep breaths. The mosquitoes are resting after (or before) the horrors of summer, and seeing hasn't yet slumped to its winter lows. I try to use my telescopes as much as I can in late autumn and late spring, but there's a problem: these are the busiest times in the academic calendar, and it's not always easy to juggle my hobby with my work. Worse, both seasons are times of unrelenting illness for any parent with young children. So it is that while the sky has been routinely clear for the last month, with seeing typically average, I haven't had much chance to exploit it. Finally, on November 13th, I felt just healthy enough to venture outside with my TSA 120. At just before midnight, Jupiter was nearing zenith. Although atmospheric conditions were not exactly ideal, I couldn't pass up the chance to have a look. I had let my TSA 120 sit outside for about 45 minutes before using it, and it paid off: while temperatures were no higher than 10 degrees Celsius, the telescope had completely cooled down. Yet when I turned to Jupiter, the planet initially resembled a circle of bubbling milk, surrounded by a smattering of drops (the Galilean moons). Why had I sacrificed sleep for this? Then, as I considered packing up, the atmosphere abruptly stabilized - and now a staggering wealth of detail shimmered into view. It was fleeting - "revelation peeps," to use a Lowellian term, often are - but it was more than enough to keep me glued to the eyepiece. Over the next hour, belts, zones, and the Great Red Spot all flickered across the pale Jovian disc, and I nearly lost track of time. Finally, it dawned on me that even a bad night's sleep was slipping away, and I hastily carried my equipment inside. Perhaps it's a character flaw that I like to obsessively compare my instruments; if so, it is a flaw I share with most amateur astronomers. In this case, I couldn't help but reflect on the TEC 140 I once owned. In a vacuum, I might prefer that telescope over the TSA 120. But the difference in the optical performance of both telescopes is slight enough that I prefer the far greater portability of my TSA 120 setup. It weighs half as much, and that makes it so much easier to use when I'm tired. Of course, when it comes to portability and ease of use it's hard to beat my EVScope 2. With Orion starting to rise high above the horizon in the wee hours of the night, I decided to use that telescope to view the constellation's famous nebula. On the 18th I parked the telescope in my backyard, found a gap in the increasingly bare trees, and had a look. As usual, within seconds the EVScope delivered a view that no traditional telescope could match under an urban sky. Yet using the telescope so soon after observing with my TSA 120 gave me a clear sense of what bothers me about it. The EVScope is easy. There are no "revelation peeps" - no flashes of transcendence - because everything is smoothed out in a (relatively) pretty picture. There's no craft to observing, no sense of taking in the universe with your own eyes. You see more - but you feel less. Sometimes, that's okay. There are whole classes of object - white dwarfs for example - that I can only glimpse with my EVScope (at least in our light-polluted skies). Yet if I were forced to give up one telescope, I would choose the EVScope without a second's hesitation. My health improved this week, and my workload (temporarily) eased. Now I steeled myself for a challenge I've dreaded for weeks: collimating my new Mewlon 210. I've been so unwilling to try it that I even - very briefly - placed the telescope for sale. Yet I read up, prepared my Allen key - and left the Mewlon out for an hour to cool down.

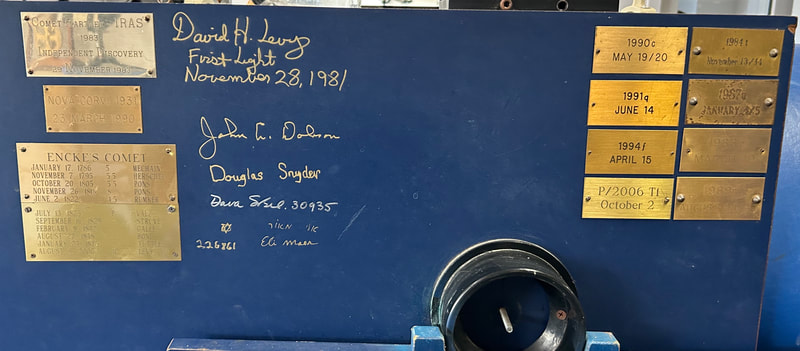

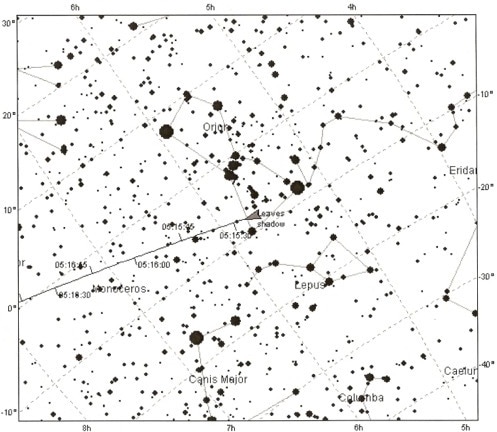

When I returned outside, I found that the telescope still had not completely acclimated to temperatures that were not far above freezing. I waited another half hour, then tried again. Now the telescope seemed cool enough, but to my surprise my first view of a star was so underwhelming that I again considered whether to sell the telescope. A blob is the best I could get - a far cry from the pinpoints I see through my refractors. I'd hoped that I'd been wrong about the Mewlon's collimation, but now there was no doubting it: the telescope's secondary mirror simply did not perfectly align with the primary. I set to work tightening bolts, and to my surprise I didn't mind it. Years of tinkering with mechanical watches and bicycles had prepared me well, I suppose, because after 15 largely painless minutes I was just about done. I could scarcely believe my eyes when I returned to that star. Instead of a blob, there was a perfect little diamond. To my amazement, the telescope's diffraction spikes - a product of the four vanes that hold its secondary mirror - actually added to the star's beauty. It wasn't perfect - seeing was actually below average - but it was about as beautiful a stellar image as I can remember seeing. Jupiter offered some of the same revelation peeps I'd enjoyed with my TSA 120, except with a bit more color (and this time, the diffraction spikes were a bit distracting at lower magnifications). Turning to the Trapezium in Orion clearly revealed five, perhaps six stars - a challenge for fine optics even in good seeing - but it was Betelgeuse that truly stole the show. The star was simply a spectacularly beautiful orange gemstone when viewed through the Mewlon. The telescope's large aperture (compared to my refractors), total lack of false color, and yes, diffraction spikes made me appreciate simple stars as I never have before. With any luck, I'll use the Mewlon to spend happy hours admiring the double stars that are easily visible in our city. But on this night, it was time to pack up - and to banish all thought of selling the Mewlon. It was midnight on September 1st, and the atmosphere was about as good as it gets for stargazing here in Washington, DC. Transparency was high, seeing was great, Saturn was high in the sky and Jupiter was wheeling over the horizon. My had prepared my TEC 140 in the living room, and prepared to haul it outside. I knew I'd have to walk for a few minutes, and I tried to figure out how best to do it. The telescope itself is just over 20 pounds. The DM-6 mount that holds it well? With its extender, also just north of 20 pounds. The Planet tripod that keeps it all stable? Another 27 pounds. With my eyepieces and including all the cases and bags that house the gear, I was looking at hauling more than 80 pounds. That might have seemed doable were it not for the size everything took up. I simply could imagine no way to drag my gear to my only nearby observing site in fewer than two - possibly three - walks. It had been a long day at work, and I was still tired from recent travels. I left my gear in place. There would be other nights. The next morning, it dawned on me that something was out of whack. Since my little backyard faces north and is usually too shrouded by leaves to be useful for astronomy, I need to be able to easily transport my gear to a more suitable spot. Last year I bought a wagon to make that easier, but dragging it around turned out to be nearly as difficult as carrying my equipment. Given my need to walk to observe, I'd long ago decided that my heaviest telescope would be a medium-sized refractor, and the TEC seemed like the best option available. Somehow, however, I'd ended up with a heap of gear that was almost impossibly heavy to walk with. What happened? Well, it turns out that in amateur astronomy - as in many other things - a sufficient number of little changes can collectively create a new paradigm. The trouble was that the TEC 140 is just a bit heavier and (especially) longer than a medium-sized mount can handle, and that required a big, hulking DM-6. Both DM-6 and TEC 140 are also just a bit too heavy for a medium-sized tripod, especially on a hard surface. Enter the Planet tripod. A medium-sized telescope therefore required gear that was heavy enough to hold something much larger. Yes, it was beautifully stable once set up. But that didn't mean much if it was too massive to move. With a heavy heart, I put my TEC 140 up for sale. Within hours, a friendly local buyer had scooped it up. While I was, on some level, sorry to let it go, it also struck me that I'd made few genuinely special memories with it. I tend to grow attached to instruments that have genuinely shown me something new. My dearly-departed TV 85, for example, revealed just how much sharper a refractor could be in our DC weather than any other kind of telescope - and gave me my first unambiguous view of the Great Red Spot. My Takahashi FC 100DC gave me truly unforgettable views of Mars, and the shadows of Jupiter's moons. My APM 140 gave me even more stunning views of Mars and Jupiter, and then the 100DZ left me breathless while gawking at the Moon. The TEC 140 did give me a wonderful sensational of texture in the Jovian clouds. But that wasn't quite enough to build a bond. After I sold my now-useless DM-6 and Planet tripod, I had some decisions to make. Should I downsize by, for example, buying a jewel-like Questar 3.5? I opted it against it after reading convinced me that the iconic little telescope could simply not compete with the also-portable 100DZ. I opted to attempt to buy two lighter but still medium-sized telescopes that I hoped could largely replace - or even improve upon - the capabilities of the TEC, while requiring a much lighter tripod and mount. The first of those telescopes: a TSA 120. Takahashi's four-inch refractors have long been my favorite telescopes. I decided to try something a little bigger in the five-inch TSA 120, an air-spaced triplet (a refractor with three lenses) that, I thought, could gather meaningfully more light than the 100 DZ. I'd long resisted buying an air-spaced triplet, since these telescopes weigh more than doublets and take much longer to cool down. The weight of the TSA 120, however, splits the difference between the TEC 140 and 100 DZ, and I figured I could simply let it acclimate in my backyard before carrying it to a more suitable observing site. To my delight, I managed to buy the TSA 120 on sale. When it arrived, I was immediately surprised by its compact size. Although its aperture is just a bit lower than that of the TEC 140, its dimensions seem closer to those of the 100DZ than the TEC 140. I also had not expected it to ship with a quality two-speed focuser. You can purchase the telescope with the bulkier but ostensibly more precise Feathertouch focuser, but Takahashi's equivalent is, to my mind, just about as good. Truth be told, I don't really understand the obsession with replacing the focusers on premium telescopes, like the Takahashi refractors. All you need is something that gets the telescope in focus, and to my mind the stock focusers do that very well. It's a small point and one I've brought up before, but still: I can't get enough of the Takahashi aesthetic. The white tube, black trim look is classic for a reason, but here's to doing something a little different. I think Ed Ting once mentioned that Takahashi telescopes have an indefinable Zen character to them, and that feels about right. It makes me inexplicably happy to see them. That's not to say that the build quality of the TSA 120 exceeds that of the TEC 140, but I do prefer that cream-colored paint with mint-green accents. Anyway, on September 14th the sky cleared and temperatures cooled just after I'd finished setting up my new TSA 120 (with Moonlite tube rings courtesy of a very helpful veteran of the Cloudy Nights forum). By then, I'd found that my Berlebach Uni tripod and (wonderful) NoH's Mount CT-20 easily support the TSA 120, which made for a setup that weighs about 40 pounds total - half as much as the TEC 140 and its equipment! I bought a Stellarvue C9S case for the TSA 120 that fits it exceptionally well, and I left the telescope outside, in its case, for about 40 minutes before using it. This time I easily walked to my nearest observing site, in the courtyard of my building. Saturn is just about a month past opposition, and high above the horizon at about 11:00 PM. I decided that its light would be the first that entered my new telescope. I have a strange relationship with Saturn. To me, it's still the most impressive object in the night sky. Yet as a target for repeat observation, it pales in comparison to Jupiter and Mars. Its rings change their tilt over time, sure, but I can rarely make out enough detail on its disk to give me the impression that I'm viewing an evolving world. Well, the TSA 120 might change that. At about 90x with my Delos 10mm eyepiece, Saturn was spectacularly well defined. I'm not sure I've ever seen such fine detail in the grey clouds above its rings. The outline of its rings was razor-sharp, the Cassini division clearly outlined. It was, I decided, about the best view I've had of the planet. Mosquitoes started to emerge, whining near my ears, but I was so distracted that I soon found myself covered in bites. I packed up and walked back home - easily. When I got inside, I was a little taken aback. I wasn't sure exactly how my view of Saturn compared to the best I had with the TEC 140; almost exactly two years ago I marveled in these pages that the bigger refractor gave me an "absolutely stunning" look at that planet. And yet, I couldn't say while unpacking the TSA 120 that I'd ever had a better view of Saturn. The sharpness is what most impressed, and the collection of bright little moons, swarming around the planet like moths around a lantern. Granted, both seeing and transparency had seemed better than average. But if the TSA 120 gave me a view that left me so satisfied, why had I hauled around so much more weight for so long? On September 15th, the pellucid evening sky invited another round with Saturn. This time, I brought out the second telescope I'd purchased: a Mewlon 210. These unusual Dall-Kirkham telescopes are a little like condensed Newtonian reflectors, with very long focal lengths. They cool down more quickly than other catadioptric telescopes - like the ubiquitous Schmidt–Cassegrain - and have none of the dew problems that can hamper these telescopes in a humid environment (Washington, DC certainly qualifies). Takahashi makes its Mewlon variants to exacting specifications, and that should in theory make them exceptional planetary telescopes. They are famously tricky to collimate, however, and they must be perfectly collimated to realize their potential. They also take a lot longer to cool down than (smaller) refractors, and their field of view is much narrower. They are much more sensitive to poor or mediocre seeing than those refractors, and the vanes that hold their little secondary mirrors produce faint rays around bright objects. The Mewlon is, therefore, a specialist instrument. Yet when conditions are right, all Mewlon variants are designed to give spectacular views of the Moon, planets, and double stars: precisely those objects I most enjoy observing in the city. At over eight inches in aperture, in good seeing the Mewlon 210 should in fact reveal those objects with even greater brightness and detail than the TEC 140. And - remarkably - it weighs much less than that telescope, despite looking much heavier. On that note, I will add that, in my view, the Mewlon 210 is quite possibly the most impressive amateur telescope to look at. It is simply beautiful. It looks like a jet engine crafted with care by a Swiss clockmaker. What's more, it comes complete with a finder scope that stays perfectly aligned with the telescope, and is so robust that you can use it as a handle. You may have to collimate the telescope from time to time, but you never have to align the finder - and that makes up for a lot. So how did the Mewlon perform on Saturn? Sadly: not as good as the TSA 120. It was clear from the box that the telescope had been handled roughly on its way to me, and something - or someone - had knocked it out of collimation. All the same, it was only a little off, and I hope I can tweak it to perfection sometime soon. Maybe in my backyard, after the leaves finally fall? Remarkably, atmospheric seeing and transparency were again above average last night, so I stepped out again with my TSA 120. This time, I waited until about midnight, when Jupiter had climbed above the horizon. I turned to Saturn first, and now the view was truly breathtaking: slightly but meaningfully more vivid - more crisp - than I'd seen even a couple nights earlier. I quickly switched to a 4.5mm Delos, giving me a magnification of exactly 200x. In my experience, Washington's sky rarely allows that kind of power. Yet to my astonishment, the atmosphere repeatedly settled down to allow a remarkably sharp view at that magnification. The subtle mingling of grey, beige, and buttermilk threads in the planet's atmosphere was simply a joy to tease out, and I could make out glimpses of structure in its ring system that I'm not sure I've ever seen before. Was this my best-ever view of Saturn? I concluded that it probably was, and again I was so enthralled that I lost track of the mosquitoes biting me. Eventually I wheeled the telescope around to Jupiter, and now the view was a little softer. The planet was still climbing out of (Earth's) thicker atmosphere near the horizon, and seeing seemed less stable in its corner of the sky. Still, I routinely made out wonderfully delicate detail in its many belts and zones. It's a little silly to compare the view through different telescopes on different nights, and perhaps sillier still to compare exceptional refractors to one another. Yet even (or perhaps especially) the most unscientific comparisons are fun, and in this case I think they're instructive. On my nights of observing, I judged that the TSA 120 showed just a bit less contrast - on Jupiter especially - than the TEC 140, and perhaps the APM 140 I once had. Yet it showed more contrast than the 100DZ - the planets seemed just a bit more vibrant - and the views were just as sharp; sharper than anything I could remember seeing through the bigger refractors. I was particularly impressed by how easily the TSA 120 snapped into focus, and how readily it gobbled up magnification. On both fronts, it seemed to exceed the performance of any telescope I've tried using. Now, all the usual caveats about the atmosphere certainly apply, but that's the point. When telescopes get to a certain quality and size, it's often factors beyond the performance of their optics that are most important. I truly did love my TEC 140. Yet I can't conclude that it's superior to the TSA 120. Both telescopes have brilliant optics that, in Washington DC, are almost invariably limited by the atmosphere, rather than their innate capabilities. Yet a setup that supports one telescope is fully twice as heavy as the other. When you're tired at the end of a long day, it doesn't take much to discourage even a quick observing session. With that in mind, the lighter, more portable setup is more often the best one. At least, it seems like it is for me. I know this is a long entry, but I can't conclude without mentioning a recent trip to the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada archive in Toronto. Since I was last there, the society's staff have set up several dozen telescopes that had me feeling like a kid in a candy store. There were two beautiful Unitron refractors, an exceptionally long Antares achromatic, a huge Cave reflector . . . the list goes on. But one in particular stood out - the ugliest one, by a long shot. Yes, that's David Levy's trusty telescope: a makeshift Dobsonian reflector complete with duct tape and what looks like a jar (!) over a finder scope. Plaques commemorating discovered comets line its base like kills on a Spitfire. Here was a poignant reminder that the best telescope - or indeed the best machine of any sort - is the one that works for you, and you alone.

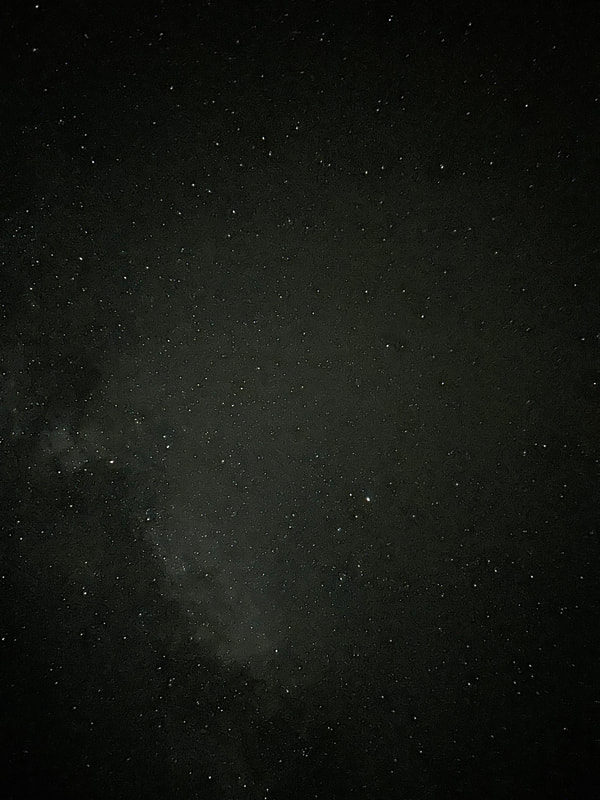

Recently, I've been on a mission to optimize my grab-and-go setup. Slowly but surely, parks that offered dark corners for a telescope have been saturated with bright lights: the kind that needlessly waste energy, confuse nocturnal animals, and pollute the night sky. I have to walk further than I have before, or settle for less than ideal observing conditions. To that end, setups that used to feel perfectly mobile now are discouragingly cumbersome to use. I admit I was tempted to swap my FC-100DZ for a lighter telescope, such as the FC-100DC I used to have and love. Then I had an epiphany - one I should have had long ago. With its diagonal removed and dew shield retracted, the DZ is just over two feet long. Couldn't I find a padded bag that long? If so, the DZ would be as easy to transport as my dearly departed TV 85, while offering considerably better performance. I found the bag - for just $23! - and wow: what a difference. It's strange but true: the DZ is as transportable as much smaller telescopes, but offers truly stunning views of everything that shines through light-polluted skies. The other night, I pointed it at Saturn, which is just now reaching opposition (its closest annual approach to Earth). The view was spellbinding, with glimpses of detail in the planet's clouds that were among the finest I've seen. On the other hand, DC's summer mosquitoes did not give me a moment's rest, and I was grateful that my little setup takes just a few minutes to disassemble. Then, last weekend, it was off for what has become an annual trip to the beach near Lewes, Delaware. I brought my EVScope 2, eagerly anticipating darker skies. Unfortunately, I soon found that atmospheric transparency was lower near the beach than it has been in years past - owing, once again, to that wildfire smoke. Worse, my recent experience with a truly pristine sky in Manitoba left me unimpressed with the view in Delaware. Sure, the Milky Way was barely, and I mean just barely, visible after fifteen minutes outside in the dark. But there was simply no comparison. I occasionally fantasize about selling my EVScope in exchange for a more capable astrophotography setup. The three (!) clear nights I experienced in Lewes reminded me why I have that fantasy - and why I haven't acted on it yet. First, the telescope needed collimation. If you've read any reviews of the EVScope, you'll know that some complain about the need to collimate such an expensive gizmo. Let me assure you that it's much easier than collimating an SCT, for example. Even when the telescope is badly misaligned - as it was for me in Lewes - the entire process takes a few minutes at most. The real problem is that Unistellar's instructions include a glaring error. To collimate the telescope, it should not be pointed at a particularly bright star - I tried Antares - because the star's brilliance will not allow you to see the secondary mirror when out of focus. I suppose it's a minor detail, but this little mistake can create a lot of frustration. Usually, it takes just moments to align the EVScope and get it ready to slew to any object you can imagine. Usually. On one night in Lewes, I had to turn off the telescope a couple times before it aligned itself. On two other nights, it did not precisely center objects after finding them - so that, at the telescope's highest magnifications, objects were simply offscreen. On a third night, everything worked seamlessly. I carefully leveled the telescope, collimated it, and waited over thirty minutes for it to acclimate. That may not sound arduous to veteran amateur astronomers - but it's hardly ideal for a grab-and-go setup. When the telescope is aligned, it tracks objects seamlessly. The trouble is that its altazimuth mount cannot perfectly track stars on long exposures. This isn't visible while peering into the eyepiece, but it does show up clearly in astrophotographs taken with the telescope. Since most people will use the telescope by staring at their phones or tablets - in fact, some Unistellar models don't even have eyepieces - this is a serious limitation. Even this six-minute exposure of the Eagle Nebula has distorted stars. Stars are also distorted - even through the eyepiece - because stars shimmer in all but the steadiest atmospheric conditions. When using a traditional telescope - especially a refractor - you may see a roving, flickering pinpoint. Yet the EVScope takes exposures to provide its bright views of deep space objects, and in these exposures the undulating pinpoints that are stars in mediocre seeing all congeal into blurry blobs. For a refractor aficionado like myself, the effect is deeply unsatisfying. To me, it really does not feel like you are actually peering into space when you use an EVScope. Occasionally I wonder: what am I getting here that I could not obtain by finding images on the internet? Have a look at this shot of the Wild Duck Cluster, for example. The problem is compounded by the reality that Unistellar's software cannot quite compensate for the effects of light pollution. Overall, it does a remarkable job - I'm still amazed that I can admire the Triangulum Galaxy from downtown DC, for example - but there's still a good deal of noise even under a Bortle 4 or 4.5 sky (as in Lewes). Have a look at this 24-minute exposure of the Pinwheel Galaxy, and notice the noise. Another inconvenient truth is that, even with the galactic core above the horizon in the summer, there just aren't that many objects that truly impress when viewed with the EVScope. You have to remember that although the EVScope allows you to view galaxies and nebulae that are far beyond the reach of a comparably-sized traditional telescope, it is also incapable of providing satisfactory views of many objects that such a telescope would reveal. Open clusters, double stars, the Moon, and the planets: everything that impresses when seen through a telescope like the Takahashi FC-100DZ is underwhelming at best when viewed with the EVScope. In practice, dozens of objects in the EVScope's catalogue look like this, and hundreds are far less impressive. The EVScope also seems to have a weak wifi signal. Walk twenty feet away, and you're likely to lose it. You can forget about sitting indoors while operating the telescope. That's too bad, because mosquitoes really can make it hard to stay outside in our muggy summers. In other places, winters are just too cold for comfortable observing. Wouldn't it be easy for Unistellar to include some way of amplifying the wifi signal on its $5,000 device? So yes, I was getting a little annoyed in Lewes. I kept imagining what my TEC 140 might reveal; not nebulae in a distant galaxy, sure, but pinpoint stars on a velvety black background, and spectacular planetary views. This is the best that the EVScope can do on Jupiter, even after a recent software update that dramatically improves planetary performance. I admit: I could go on. Suffice it to say that my nights in Lewes reminded me that, if you buy an EVScope, you really should go for the EVScope 2. This is because the eyepiece is really a lot better than some reviews suggest. Somehow, images of nebulae and galaxies are much brighter and sharper through the eyepiece than they appear to be when viewed on a phone or tablet. The distortions I complained about above - those blurred stars, in particular - are also minimized when viewed through the eyepiece, likely because the small scale of the image mitigates them. As a result, I am consistently impressed by the nebulae and galaxies I see through the eyepiece; so impressed that I take an image that then disappoints. Just before I took the image of the Pinwheel Galaxy that you've already seen, I invited my wife and our friend outside to have a look. Both are astronomy novices, to put it mildly. Both seemed skeptical that they'd see much. Yet when both craned over the EVScope eyepiece, they gasped. They could not believe that they had seen a whole galaxy across 20 million years in time and space. They kept saying how cool it was. "It's almost like one of those picture slide viewers," my friend eventually said. Indeed. You see so much more - and so much less - than you would with an ordinary telescope. That is why I think I'll keep the EVScope . . . for now. Here are some extra images, showing medium-length exposures of some of the best-known sights in the summer sky. Last week, we made what used to be an annual pilgrimage to Riding Mountain National Park, a 3,000-kilometer expanse near the border of Saskatchewan and Manitoba. Home to one of North America's largest populations of black bears, the park boasts a Bortle 1 sky: the darkest you can find on planet Earth. One of the greatest wonders I've experienced in amateur astronomy was that night sky, some ten years ago. I convinced my then girlfriend - now wife - to join me on a drive down a gravel road, flanked by dense forest. We stepped out in a clearing and oh, that sky. Our eyes weren't fully dark adjusted, but there was the Milky Way, boiling with exquisite clarity across a truly coal-black background. And the stars! I remember being stunned by their vivid colors: blue, red, yellow, and white, gemstones strung across the galactic core. Then we heard yips and yelps in the darkness, from the other side of the road - coyotes? Wolves? We dashed into the car. Unfortunately there are just a lot of animals in Riding Mountain that can kill a human, and most come out with the stars. There's a large pack of wolves (I stumbled across one of their kills once, complete with fresh paw prints), a host of lynx, plenty of bobcats, a healthy population of coyotes, a smattering of cougars, and more than a thousand bears - to say nothing of big herbivores that don't like to be startled. Most - all? - can see better in the dark than humans can. There wasn't enough room in our van to pack my Winnipeg telescope, but still: this time, I was determined to have a longer look at the sky. Things got off to an inauspicious start when, at about 10:00 PM on the first clear night, I nearly walked into a giant black bear near our cabin. It ran off into the undergrowth, the branches swaying and cracking as it disappeared. I hurried back to safety. I consoled myself with the knowledge that a thin haze of wildfire smoke would have dimmed the stars. The next night was perfectly clear, however; mercifully, the smoke had drifted east. I steeled myself and, at midnight, crept out of my cabin. It was dark - I could barely make out my hand in front of my face - but I knew roughly where I was going. When I got to about 50 feet away from the cabin, the dread started to set in. Yet my eyes were adapting to the dark, and to my delight I could start to make out the Milky Way. I inched forward, and at about 100 feet away I could clearly discern the galaxy arcing from one horizon to the next. What a sight! But closer to Earth, I couldn't see a thing, and my fear was getting hard to manage. Every noise, I was sure, was a predator creeping closer. I hurried back inside, and yes I was relieved to close the door. On the following night, the sky was again perfectly clear. This time, I lingered nearer my cabin, but I set up my phone and captured a ten-second exposure of the sky - then another, and another. You can see the results above. Yet they don't quite capture what the view was really like, beyond the glow of the cottage lights. It filled me with awe to see the Milky Way with such clarity - and, if I'm honest, profound regret at being sequestered in a big city. What I wouldn't give to live under a truly dark sky! Ralph Waldo Emerson famously wrote that: "If the stars should appear one night in a thousand years, how would men believe and adore, and preserve for many generations the remembrance of the city of God!" That resonated with me. Nearly all of us have lost the true wonder of the heavens: the humbling perspective of our impossibly immense galaxy, with its countless Suns and Earths, stretching around and above us. Catching a glimpse now and then is the best we can hope for - and indeed, what an impression it then makes. Things clouded over by morning, but the view scarcely worsened. We drove out to join the bison, and they put on a show. But of course, I couldn't stop thinking about the night sky on the pre-Columbian plains. I'm not sure historians have begun to process what it meant for us, as a species, when most of us lost that view. At least these bison still enjoy it.

To put it mildly, it's been a dreadful summer for astronomy in Washington, DC. The primary culprit is wildfire smoke, which seems to waft into the city with every clear night. As a professor whose primary preoccupation is climate change - and as a dad - the smoke fills me with dread. It is alarming for any number of reasons, but it has extra significance for those enamored with the night sky. The atmosphere is likely to be less transparent on a warming planet, owing either to wildfire smoke or aerosols intentionally seeded into the stratosphere. That second possibility is known as solar geoengineering. It's cheap (compared to the cost of global warming), it's likely to be effective (despite a litany of troubling side effects), and I'm increasingly convinced it will happen within twenty years. In fact, this summer the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy released a primer that more or less accurately describes where the science of geoengineering currently stands. If plans currently on the drawing board someday take off, astronomy as a science and hobby will change - quite possibly for the rest of our lives. In all likelihood, planetary observation won't change much, and Electronically-Assisted Astronomy will still reveal deep space marvels. Yet my suspicion is that traditional telescopes - including big Dobsonian reflectors - will be far less effective for observations of diffuse objects far from our Solar System, such as nebulae or galaxies. You've been warned! Anyway, I did manage to see one spectacular sight in DC this summer. In May - just before the worst of the smoke surged south - a supernova exploded in the Pinwheel Galaxy. I hauled my EVScope to a nearby field and had a look. The above picture is all I managed to capture, but the view through the eyepiece was far more impressive. I still can't believe I managed to see an exploding star - and, in all likelihood, the formation of a black hole - 21 million light years from Earth. More recently, I travelled with my family to Winnipeg. Despite its closer proximity to the many wildfires burning through British Columbia, the city has been less affected by wildfire smoke than Washington, DC. The sky is not quite free of smoke, but it's a good deal more transparent than it's been further south. This was my first trip to the city since the pandemic, and I'd nearly forgotten that I cobbled together a fairly impressive little observing setup here. Four years ago, I had a Twilight I mount delivered to my in-laws. I also purchased a C6 shortly after I was last here, and it was still in the box when I arrived this time. I unpacked it with some trepidation - the last C6 I purchased was damaged upon arrival - but not to worry: to my relief, the little telescope was in perfect condition. With everything assembled, I was struck by how well the C6 fits on the Twilight mount. I don't think it could handle a C8, but a C6 is just about perfect. It's quite stable, convenient to look through, and remarkably easy to move. In fact, I can lift mount, tripod, telescope, diagonal, and eyepiece - everything - above my head with ease. I swapped out the standard Celestron diagonal - a child's toy - with a TeleVue Everbrite, and used a Baader Mark IV Zoom for an eyepiece. The field of view, I must admit, is a little too narrow, but then a Schmidt–Cassegrain really isn't a wide-field instrument. I was gifted one clear night after another since arriving here, and used the first two nights to admire the Moon. This far north, it doesn't rise far above the horizon right now, and it is tinted a beautiful pinkish-gold by the diffuse smoke in the upper atmosphere. Seeing was mediocre at best, but the telescope turned out to be well collimated, and the view was quite striking. As the above image attests, the Moon was not as sharp as it would be through one of my refractors. Even in mediocre atmospheric conditions that prevailed here, the Takahashi, I'm sure, could have shown me more. But when you consider the relatively low cost of a C6 - albeit much higher than it was pre-pandemic - the telescope is a remarkable performer. I was particularly impressed by how cleanly it snapped into focus; in fact, finding focus seemed a little easier with the C6 than it is with my refractors. I was genuinely delighted to discover that Saturn now rises high enough above the horizon to observe at around midnight. The planets might have drawn me outdoors this summer despite the wildfire smoke, but often they had set before I could step outside. Well - Saturn, at least, is back.

The C6 offered a really satisfying view of the planet, with the Cassini Division clearly visible at 75x. I'm not sure my Takahashi would have done that much better, given the seeing. In a cooperative atmosphere, I have no doubt that the refractor would outpace the Schmidt–Cassegrain; there is a delightful crispness to its views that the stubbier telescope can't quite match. And of course, it never needs to collimate or acclimate (for long). Nevertheless, I was stunned when, later, the C6 showed me Arcturus as a perfect orange point: something I had not expected from a Schmidt–Cassegrain. For those less obsessed than I am with getting the absolute best views that a (modest) aperture can provide, I suspect it would be impossible to justify the extra cost of a 4" apochromatic refractor over a C6. Well done, Celestron! Anyway, I had a truly wonderful half hour on the porch, the crickets chirping nearby as I admired the ethereal beauty of Saturn's rings. I was struck by how much their tilt relative to us has changed over the past year, and I fear that they will - briefly - disappear from view entirely in the months to come. It will be fleeting. Soon enough, the rings will return, and the planet will regain its grandeur. For me, one of the joys of astronomy lies in the knowledge that however badly we muck up our planet, countless wonders glitter beyond our reach. With or without us, it's a beautiful universe. Often, around this time of the year, the unstable atmosphere of winter yields to the more settled air of spring in Washington, DC. With the mosquitoes a month or two away, now is the time to observe as much as possible. The planets are all lined up at sunset, but unfortunately that part of the sky is obscured in all my nearby observing spots. Instead, for two nights over the past week, I've enjoyed a world much nearer our own. Today the sky was a beautiful, deep azure, and tonight's forecast called for good seeing with fair transparency. I decided conditions were good enough to exert a little more effort than usual. I hauled out my TEC 140 - now on a hulking Berlebach Planet tripod - and found a nook not far from my backyard. At this time of the year, budding leaves are just beginning to make my backyard unusable for astronomy. Turning to the Moon, I was disappointed - if not exactly surprised - to realize that the forecast had, again, gotten it wrong. Seeing seemed mediocre at best, and the atmosphere had that soft, milky quality that often frustrates planetary and lunar viewing. As my eyepieces and, to a lesser extent, my telescope cooled down, the atmosphere between me and the Moon started to stabilize - or, rather, it started dip into fleeting moments of clarity. Especially compelling in these "revelation peeps" - using Percival Lowell's terminology, as I've mentioned in an earlier entry - was Schickard crater, the massive walled plain clearly visible towards the center-right of this picture: Schickard's crater floor - that walled plain - was alive with irreducible detail, including countless tiny craterlets. As Eugene Shoemaker established at the dawn of the Space Age, the layering of lunar features provides a roadmap to their age. Signs of bombardment on the floor and walls of a big crater provide clear evidence that the big crater is very old. Of course, the little craters scattered around the big crater would have formed long after the big one. I love looking at the Moon as a geologist might, and I am always especially drawn to features on which observers have reported transient lunar phenomena (TLPs). Influential amateur Patrick Moore, for example, reported what seemed like a mist over Shickard just before Hitler's army invaded Poland in 1939. This time, however, all was crystal-clear. It was not my first lunar experience of the week. Several nights ago, I stepped out with my most portable setup - the Takahashi FC-100DZ on a photographic tripod - because atmospheric conditions were forecast to be mediocre at best. I'm glad I did! After I set up - with only my Baader variable zoom eyepiece in hand - I turned to the Moon and realized that, in fact, seeing was far better than average. Have a look at the picture above. Comparing it to the picture that begins this entry will reveal that, for amateur astronomers, the state of the atmosphere can be so much more important than the capabilities of a telescope. The first image was taken by a telescope that costs well over twice as much, and gathers more than twice as much light, as the one that provided that second image. Yet the second image is clearly far better. Here's a close-up of my favorite stretch of the Moon: the wonderfully diverse landscape winding from Plato (top) and Vallis Alpes down through Mare Imbrium to Archimedes, Erastosthenes, and finally spectacular Copernicus, here largely enveloped in shadow. Many of these features - or environments, as I prefer to think of them - have a rich and often bizarre history. Across some three hundred years, scientists compared them to features on Earth, speculated about their supposed inhabitants, tracked their alleged changes, and finally explored them through the voyages of crewed and robotic spacecraft.

Just look at the extraordinary detail the little Takahashi reveals - and remember that, as usual, this is an iPhone picture that blurs what is visible to the naked eye. Honestly, if you're into lunar exploring, you don't need more than a quality four-inch refractor. Seeing was forecast to be mediocre yesterday, and atmospheric transparency will below average. But the Moon rose exceptionally early - it was high in the sky by early afternoon - and therefore within range of my backyard. It had been a couple months since I was out with a telescope, owing to the turbulent winter atmosphere here in DC. I had to scratch the itch. As usual, I set up my Takahashi FC-100DZ in moments, this time with my CT-20 mount attached to the Berlebach Uni tripod. This was a lightweight but rock-solid setup, and as usual the refractor cooled down in just a few minutes. As the sky darkened to an indigo blue, I wheeled the telescope over to the Moon - and was stunned. Seeing, it turned out, was a good deal better than average - and the Moon was just beautifully sharp through my 24mm Panoptic eyepiece (which gives a magnification of just over 33x). Check it out, now at 80X with a 10mm Delos: Very striking last night was my favorite lunar crater, giant Plato, which as I've discussed in this blog was the focus of efforts to detect lunar environmental changes - and perhaps signs of life - in the nineteenth century. Many contemporary observers sought to measure shifts in the crater rim's shadows, which supposedly betrayed evidence for an atmosphere. Ever since reading their logbooks, these shadows had a special significance for me - and now I always try to see them change. No luck yet! The cluster of tiny (from our perspective) craterlets on Plato's floor are often a test of good seeing and great optics, and I think I could just make out a few of them last night. Then I wheeled over to the mass of giant, craggy craters along the Moon's southern terminator, which always provide a spectacular view. Copernicus, quite possibly the most striking lunar crater, is so impressive when the Moon is around halfway illuminated. Occasionally the atmosphere seemed entirely stable, and when it did the crater snapped into exquisite detail. Copernicus was the target of Eugene Shoemaker's pioneering, 1962 study on lunar stratigraphy, which helped unearth a kind of Rosetta stone for deciphering the history of the Moon's landscapes. Looking at the layers upon layers around the crater, now at 175x, it's easy to see why: Last night was a reminder to be wary of seeing forecasts. As I've experienced before, they can be really inaccurate - and in any case, seeing can vary from part of the sky to another. I'm going to try to avoid staying in on a clear night because bad seeing is forecast; next time that happens, I'm going to have a look for myself.

|

Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed