|

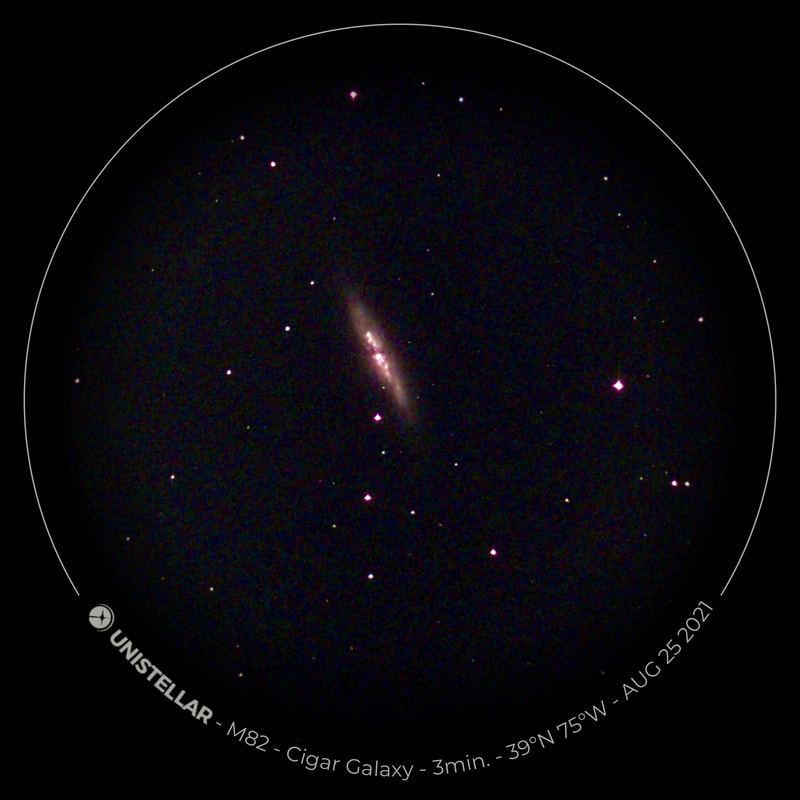

Electronically Assisted Astronomy (EAA) has been around for a while. Not long ago, you'd get into it by buying a camera, attaching it to your eyepiece, hooking it to a monitor, and then watching as it combined - or "stacked" - images of nebulae or galaxies. Before long, the image on the monitor would take on the recognizable shape and color of a deep space object that, viewed unaided through the eyepiece, appeared as little more than a barely-perceptible smudge. Gone was the romance of peering at the space beside that smudge (using averted vision) and imagining, say, the combined light of 250 billion stars. But, if we're being honest, the magic got a little stale when squinting at one equally dim blob after another. EAA offered no substitute for looking through a big Dobsonian under a dark sky. Its images paled in comparison to those that could be taken with a complicated astrophotography rig. But for those of us stuck in the city and unwilling or unable to try serious astrophotography, EAA let us see what otherwise seemed out of reach: the universe beyond our solar system. A few years ago, two startups - Unistellar and Vaonis - took the obvious next step by debuting an integrated telescope, go-to mount, tripod, and stacking camera. Both the EVScope (Unistellar) and Stellina (Vaonis) were small, portable, and remarkably easy to use compared to any telescope on the market. Both were priced far beyond the cost of their parts; it is, after all, expensive to sell a niche product as a brand-new company. Still, despite the exorbitant cost - I shudder to think of what I paid for my EVScopes - enough people bought the new "smart" telescopes that both companies seem to have prospered. When both the EVScope and Stellina succeeded, it was clear that amateur astronomy would never be quite the same. The technology would keep improving, and bigger, more established companies would get in the game. A maturing market, meanwhile, would permit economies of scale. Those who waited on getting the first-generation EVScope or Stellina reasoned - correctly - that prices would soon collapse. Anyway, I bought my EVScope 2 for about $5,000. Recently, Vaonis released its next-generation Vespera II for about $1,600. The Vespera II is much more compact, it has a more sensitive sensor, it focuses itself (unlike the EVScope), and it's built around an apochromatic refractor that, in theory, should yield sharper images. I sold my EVScope and used the funds to purchase the new Vespera - and a few other things, because wow that price difference is huge. These are two approximately 10-minute exposures of the Orion Nebula. Atmospheric transparency and seeing were about average - maybe a little worse than average - while I took the picture on the left. Both conditions were definitely above average while I captured the shot on the right. Believe it or not, Orion was also much higher in the night sky while I took the picture on the right than when I took the image on the left. Of course, I took the picture on the left with the $1590 Vespera II and its $229 light pollution filter, while I took the image on the right with the EVScope 2, which is now on sale for $4,409. The Vespera focuses itself, but I'd carefully collimated the EVScope before using. I expected a difference in performance, sure, but the magnitude of that difference still astonished me. Actually, these pictures do not reveal the biggest distinction between the two images. Because of the Vespera's shorter focal length and more sensitive sensor, its images capture far more of the night sky. In fact, its new "CovalENS" feature allows for the integration of multiple stacked images of adjacent corners of the night sky, which should enable sweeping mosaics of, say, the entire Andromeda Galaxy. And I should emphasize again that the Vespera is much smaller and more portable than the EVScope. Admittedly, the EVScope comes with a tripod, while the Vespera does not (though again, the Unistellar backpack is much pricier than the one offered by Vespera). And the EVScope does have other advantages over the Vespera. It has an eyepiece, so if you want to use it like a regular telescope, you can. As I've often reported in these pages, the view through the EVScope eyepiece looks better than the pictures, though I suspect this is partly because the image is smaller. Magnifying the image on the bigger screen of a phone - let alone an iPad or laptop - reveals its imperfections. The Vespera also looks like something built by Apple, seemingly to appeal to buyers who see Apple as the gold standard for sophisticated, problem-free technology. It's a problem. The telescope's sleek surface is slippery and difficult to handle, especially in the cold. Screwing it into or out of a tripod is frightening. It wobbles dangerously and threatens to plummet to the ground (not a problem with the EVScope). It's also easy to accidentally open the Vespera, since there's nothing to lock the optical tube in place until needed, and the power button is far too easy to activate while holding the telescope. The button shines with a bright blue light when it's on. That will be familiar to users of common consumer products, but any amateur astronomer will tell you that a bright blue light is exactly what you don't want as your eyes adjust to the dark. Unlike the EVScope and other competitors now on the market, in important ways the Vespera prioritizes form over function. There's more. Whereas the EVScope has no problem with nearby street lights, the Vespera's lack of a dew shield allows those lights to easily create distortions in the image. Horizontal lines at the top corner of my images, I was told, are the product of a nearby (but not particularly bright) light. The lack of a dew shield is also, of course, a ticket to frustration in cold or humid climates (Washington, DC can be both). Vespera sells a screw-in Hygrometer Sensor - for an extra $119.

Then there's the lack of citizen science. Unlike Unistellar, Vespera has no fancy partnerships with the big guns in space science. If you want to join my friends at the SETI Institute in searching for exoplanets, you're out of luck. And if you want to help NASA track its spacecraft, stick to the EVScope. The biggest problem with the Vespera II, however, is battery life. The EVScope 2 can keep imaging for up to nine hours, and other Unistellar models do even better. By contrast, the Vespera has four hours of battery life - supposedly. I found that its battery consistently dropped down to 85% capacity after I had set it up, which takes over five minutes (setup was much quicker with the EVScope 2). In subzero temperatures, I suspect I could squeeze about three hours out of the telescope. Storage capacity is also much lower in the Vespera II, compared to the EVScope 2, but to me that doesn't matter; I always move good pictures to my phone's photo album. So do the many little shortcomings of the Vespera II, relative to the EVScope 2, overwhelm the advantages of its sharper, bigger, more colorful images, its autofocusing, and its more portable size and weight? The answer is: no, not even close. At present I think the new Vespera is simply a much more capable telescope, and again: it's sold at a fraction of the cost. In fact, I now fear for the future of Unistellar. The likes of Celestron and ZWO are offering telescopes that target both the high and low ends of the smart telescope market. I suspect that, if Unistellar stays in business, it will owe a lot to the connections its founders wisely made with SETI and NASA. I should say that I've reached my conclusions primarily by observing the Orion Nebulae. Planetary images, I suspect, are better with the EVScope 2 than the Vespera II, owing in part to the former's greater focal length and aperture. But that's really not why I'd want to use EAA. Even my C90, for example, gives a vastly better view of Jupiter than the EVScope could provide at twenty times the cost. Of course, as I've often described in these pages, all smart telescopes have the same shortcoming. To use them you wait around and stare at a screen. There's still something different - something special - about looking through a glass eyepiece instead, at age-old light at it shimmers through our roiling atmosphere.

0 Comments

If November isn't my favorite month to observe here in Washington, DC, it's right up there with March and April. Most nights are cool, crisp, and imbued with an ineffable fragrance - of decaying leaves in autumn, of budding blossoms in spring - that encourages deep breaths. The mosquitoes are resting after (or before) the horrors of summer, and seeing hasn't yet slumped to its winter lows. I try to use my telescopes as much as I can in late autumn and late spring, but there's a problem: these are the busiest times in the academic calendar, and it's not always easy to juggle my hobby with my work. Worse, both seasons are times of unrelenting illness for any parent with young children. So it is that while the sky has been routinely clear for the last month, with seeing typically average, I haven't had much chance to exploit it. Finally, on November 13th, I felt just healthy enough to venture outside with my TSA 120. At just before midnight, Jupiter was nearing zenith. Although atmospheric conditions were not exactly ideal, I couldn't pass up the chance to have a look. I had let my TSA 120 sit outside for about 45 minutes before using it, and it paid off: while temperatures were no higher than 10 degrees Celsius, the telescope had completely cooled down. Yet when I turned to Jupiter, the planet initially resembled a circle of bubbling milk, surrounded by a smattering of drops (the Galilean moons). Why had I sacrificed sleep for this? Then, as I considered packing up, the atmosphere abruptly stabilized - and now a staggering wealth of detail shimmered into view. It was fleeting - "revelation peeps," to use a Lowellian term, often are - but it was more than enough to keep me glued to the eyepiece. Over the next hour, belts, zones, and the Great Red Spot all flickered across the pale Jovian disc, and I nearly lost track of time. Finally, it dawned on me that even a bad night's sleep was slipping away, and I hastily carried my equipment inside. Perhaps it's a character flaw that I like to obsessively compare my instruments; if so, it is a flaw I share with most amateur astronomers. In this case, I couldn't help but reflect on the TEC 140 I once owned. In a vacuum, I might prefer that telescope over the TSA 120. But the difference in the optical performance of both telescopes is slight enough that I prefer the far greater portability of my TSA 120 setup. It weighs half as much, and that makes it so much easier to use when I'm tired. Of course, when it comes to portability and ease of use it's hard to beat my EVScope 2. With Orion starting to rise high above the horizon in the wee hours of the night, I decided to use that telescope to view the constellation's famous nebula. On the 18th I parked the telescope in my backyard, found a gap in the increasingly bare trees, and had a look. As usual, within seconds the EVScope delivered a view that no traditional telescope could match under an urban sky. Yet using the telescope so soon after observing with my TSA 120 gave me a clear sense of what bothers me about it. The EVScope is easy. There are no "revelation peeps" - no flashes of transcendence - because everything is smoothed out in a (relatively) pretty picture. There's no craft to observing, no sense of taking in the universe with your own eyes. You see more - but you feel less. Sometimes, that's okay. There are whole classes of object - white dwarfs for example - that I can only glimpse with my EVScope (at least in our light-polluted skies). Yet if I were forced to give up one telescope, I would choose the EVScope without a second's hesitation. My health improved this week, and my workload (temporarily) eased. Now I steeled myself for a challenge I've dreaded for weeks: collimating my new Mewlon 210. I've been so unwilling to try it that I even - very briefly - placed the telescope for sale. Yet I read up, prepared my Allen key - and left the Mewlon out for an hour to cool down.

When I returned outside, I found that the telescope still had not completely acclimated to temperatures that were not far above freezing. I waited another half hour, then tried again. Now the telescope seemed cool enough, but to my surprise my first view of a star was so underwhelming that I again considered whether to sell the telescope. A blob is the best I could get - a far cry from the pinpoints I see through my refractors. I'd hoped that I'd been wrong about the Mewlon's collimation, but now there was no doubting it: the telescope's secondary mirror simply did not perfectly align with the primary. I set to work tightening bolts, and to my surprise I didn't mind it. Years of tinkering with mechanical watches and bicycles had prepared me well, I suppose, because after 15 largely painless minutes I was just about done. I could scarcely believe my eyes when I returned to that star. Instead of a blob, there was a perfect little diamond. To my amazement, the telescope's diffraction spikes - a product of the four vanes that hold its secondary mirror - actually added to the star's beauty. It wasn't perfect - seeing was actually below average - but it was about as beautiful a stellar image as I can remember seeing. Jupiter offered some of the same revelation peeps I'd enjoyed with my TSA 120, except with a bit more color (and this time, the diffraction spikes were a bit distracting at lower magnifications). Turning to the Trapezium in Orion clearly revealed five, perhaps six stars - a challenge for fine optics even in good seeing - but it was Betelgeuse that truly stole the show. The star was simply a spectacularly beautiful orange gemstone when viewed through the Mewlon. The telescope's large aperture (compared to my refractors), total lack of false color, and yes, diffraction spikes made me appreciate simple stars as I never have before. With any luck, I'll use the Mewlon to spend happy hours admiring the double stars that are easily visible in our city. But on this night, it was time to pack up - and to banish all thought of selling the Mewlon. Recently, I've been on a mission to optimize my grab-and-go setup. Slowly but surely, parks that offered dark corners for a telescope have been saturated with bright lights: the kind that needlessly waste energy, confuse nocturnal animals, and pollute the night sky. I have to walk further than I have before, or settle for less than ideal observing conditions. To that end, setups that used to feel perfectly mobile now are discouragingly cumbersome to use. I admit I was tempted to swap my FC-100DZ for a lighter telescope, such as the FC-100DC I used to have and love. Then I had an epiphany - one I should have had long ago. With its diagonal removed and dew shield retracted, the DZ is just over two feet long. Couldn't I find a padded bag that long? If so, the DZ would be as easy to transport as my dearly departed TV 85, while offering considerably better performance. I found the bag - for just $23! - and wow: what a difference. It's strange but true: the DZ is as transportable as much smaller telescopes, but offers truly stunning views of everything that shines through light-polluted skies. The other night, I pointed it at Saturn, which is just now reaching opposition (its closest annual approach to Earth). The view was spellbinding, with glimpses of detail in the planet's clouds that were among the finest I've seen. On the other hand, DC's summer mosquitoes did not give me a moment's rest, and I was grateful that my little setup takes just a few minutes to disassemble. Then, last weekend, it was off for what has become an annual trip to the beach near Lewes, Delaware. I brought my EVScope 2, eagerly anticipating darker skies. Unfortunately, I soon found that atmospheric transparency was lower near the beach than it has been in years past - owing, once again, to that wildfire smoke. Worse, my recent experience with a truly pristine sky in Manitoba left me unimpressed with the view in Delaware. Sure, the Milky Way was barely, and I mean just barely, visible after fifteen minutes outside in the dark. But there was simply no comparison. I occasionally fantasize about selling my EVScope in exchange for a more capable astrophotography setup. The three (!) clear nights I experienced in Lewes reminded me why I have that fantasy - and why I haven't acted on it yet. First, the telescope needed collimation. If you've read any reviews of the EVScope, you'll know that some complain about the need to collimate such an expensive gizmo. Let me assure you that it's much easier than collimating an SCT, for example. Even when the telescope is badly misaligned - as it was for me in Lewes - the entire process takes a few minutes at most. The real problem is that Unistellar's instructions include a glaring error. To collimate the telescope, it should not be pointed at a particularly bright star - I tried Antares - because the star's brilliance will not allow you to see the secondary mirror when out of focus. I suppose it's a minor detail, but this little mistake can create a lot of frustration. Usually, it takes just moments to align the EVScope and get it ready to slew to any object you can imagine. Usually. On one night in Lewes, I had to turn off the telescope a couple times before it aligned itself. On two other nights, it did not precisely center objects after finding them - so that, at the telescope's highest magnifications, objects were simply offscreen. On a third night, everything worked seamlessly. I carefully leveled the telescope, collimated it, and waited over thirty minutes for it to acclimate. That may not sound arduous to veteran amateur astronomers - but it's hardly ideal for a grab-and-go setup. When the telescope is aligned, it tracks objects seamlessly. The trouble is that its altazimuth mount cannot perfectly track stars on long exposures. This isn't visible while peering into the eyepiece, but it does show up clearly in astrophotographs taken with the telescope. Since most people will use the telescope by staring at their phones or tablets - in fact, some Unistellar models don't even have eyepieces - this is a serious limitation. Even this six-minute exposure of the Eagle Nebula has distorted stars. Stars are also distorted - even through the eyepiece - because stars shimmer in all but the steadiest atmospheric conditions. When using a traditional telescope - especially a refractor - you may see a roving, flickering pinpoint. Yet the EVScope takes exposures to provide its bright views of deep space objects, and in these exposures the undulating pinpoints that are stars in mediocre seeing all congeal into blurry blobs. For a refractor aficionado like myself, the effect is deeply unsatisfying. To me, it really does not feel like you are actually peering into space when you use an EVScope. Occasionally I wonder: what am I getting here that I could not obtain by finding images on the internet? Have a look at this shot of the Wild Duck Cluster, for example. The problem is compounded by the reality that Unistellar's software cannot quite compensate for the effects of light pollution. Overall, it does a remarkable job - I'm still amazed that I can admire the Triangulum Galaxy from downtown DC, for example - but there's still a good deal of noise even under a Bortle 4 or 4.5 sky (as in Lewes). Have a look at this 24-minute exposure of the Pinwheel Galaxy, and notice the noise. Another inconvenient truth is that, even with the galactic core above the horizon in the summer, there just aren't that many objects that truly impress when viewed with the EVScope. You have to remember that although the EVScope allows you to view galaxies and nebulae that are far beyond the reach of a comparably-sized traditional telescope, it is also incapable of providing satisfactory views of many objects that such a telescope would reveal. Open clusters, double stars, the Moon, and the planets: everything that impresses when seen through a telescope like the Takahashi FC-100DZ is underwhelming at best when viewed with the EVScope. In practice, dozens of objects in the EVScope's catalogue look like this, and hundreds are far less impressive. The EVScope also seems to have a weak wifi signal. Walk twenty feet away, and you're likely to lose it. You can forget about sitting indoors while operating the telescope. That's too bad, because mosquitoes really can make it hard to stay outside in our muggy summers. In other places, winters are just too cold for comfortable observing. Wouldn't it be easy for Unistellar to include some way of amplifying the wifi signal on its $5,000 device? So yes, I was getting a little annoyed in Lewes. I kept imagining what my TEC 140 might reveal; not nebulae in a distant galaxy, sure, but pinpoint stars on a velvety black background, and spectacular planetary views. This is the best that the EVScope can do on Jupiter, even after a recent software update that dramatically improves planetary performance. I admit: I could go on. Suffice it to say that my nights in Lewes reminded me that, if you buy an EVScope, you really should go for the EVScope 2. This is because the eyepiece is really a lot better than some reviews suggest. Somehow, images of nebulae and galaxies are much brighter and sharper through the eyepiece than they appear to be when viewed on a phone or tablet. The distortions I complained about above - those blurred stars, in particular - are also minimized when viewed through the eyepiece, likely because the small scale of the image mitigates them. As a result, I am consistently impressed by the nebulae and galaxies I see through the eyepiece; so impressed that I take an image that then disappoints. Just before I took the image of the Pinwheel Galaxy that you've already seen, I invited my wife and our friend outside to have a look. Both are astronomy novices, to put it mildly. Both seemed skeptical that they'd see much. Yet when both craned over the EVScope eyepiece, they gasped. They could not believe that they had seen a whole galaxy across 20 million years in time and space. They kept saying how cool it was. "It's almost like one of those picture slide viewers," my friend eventually said. Indeed. You see so much more - and so much less - than you would with an ordinary telescope. That is why I think I'll keep the EVScope . . . for now. Here are some extra images, showing medium-length exposures of some of the best-known sights in the summer sky. For amateur astronomers, two things happen to the atmosphere around this time of year in Washington, DC: in general, transparency improves, and seeing - meaning, of course, stability - deteriorates. Daytime brings deep blues, sunset a beautiful gradient from azure to scarlet, and nighttime brilliant winter stars in a velvet tapestry (when not facing towards the National Mall, at least). At the same time, the stars noticeably twinkle far more than they do in summer, and moments of steady seeing become ever rarer. The muggy, mosquito-plagued nights of summer, when the planets can very occasionally look like little Hubble photos viewed from afar, are now a distant memory. All the same, since keeping this blog I've found autumn to be my favorite time to observe. It's just so much more comfortable being outside, the planets are still high in the sky, and my refractors at least give me a puncher's chance of making out some detail on them, even in nights of mediocre seeing. With that in mind, I stepped out on the 14th, Takahashi in hand, and found a nook near my mostly tree-covered backyard that afforded me a good view of Mars. It was cold by DC standards - around freezing - but my telescope was well acclimated and the view was beautifully sharp. The Martian south pole in particular looked large and sort of smeared; not quite as brilliant as it can, but larger in dimensions. Later, a spectacular set of pictures posted by Peter Gorczynski over at CloudyNights.com revealed the cause: a swirl of clouds around the pole that were barely visible to me in the mediocre seeing. I didn't last long in the cold weather, and over the next week seeing here in DC grew worse - but transparency remained better than average. I decided to test out the Unistellar EVScope 2 on the comparatively few but spectacular deep space objects that are beginning to climb high above the horizon in our late autumn sky. On the 22nd, I marched about 20 minutes uphill from my house to my daughter's school. Its field is now the nearest I know that is not completely saturated with light, and I can only hope it stays that way. It's not hard to haul the EVScope that distance, thanks to the relatively ergonomic backpack it comes with, and I can only emphasize yet again how absurdly easy it is to set up the telescope once I'm in position. It takes no more than a minute to have the EVScope fully aligned and tracking my first target. It quickly and easily hooks into its tripod, immediately connects to my phone, and in just moments aligns with the night sky and slews to my first target. It takes me two or three times longer to set up my refractors on their sample manual mounts, which of course don't have any software at all. Other tracking amounts, even the simplest ones (such as the iOptron AZ Mount Pro I own), require far more steps to set up, and often don't quite align perfectly; it's why I inevitably favor manual mounts when stepping out with my refractors. I'm not sure how Unistellar leapfrogged all the established brands in amateur astronomy by offering a mount that truly is plug and play - but they have, and it's wonderful. After I let the telescope cool down, I turned to the Orion Nebula. In the past, I've tended to focus too much on my phone while the telescope slowly integrated its pictures and the view of my target gradually brightened. This time I favored the eyepiece, which as I've written elsewhere is much improved on the EvScope 2. I now noticed that the eyepiece view seemed much sharper and, to my surprise, three-dimensional than the image on my phone. The dark nebula jutting in front of the familiar crescent of the Orion Nebula, for example, truly looked as though it was in the foreground, and I followed a fascinating zigzag pattern of dark nebulosity weaving across the bright core that mostly washed out in the phone image. The EVScope permits easy if relatively low-resolution astrophotography, but the current iteration at least is really designed for observing. I've complained that using the EVScope is a very different experience from using a traditional telescope, because I've tended to wait around for the images to integrate on my phone. This time, I was glued to the eyepiece - and it really did feel like a proper observing experience. The EVScope 2 improves considerably over its predecessor, and the Unistellar software has continually added new capabilities. Just have a look at the image of the Orion Nebula that I took almost exactly two years ago, and compare it with this week's version. I suspect I could further improve the view through the EVScope 2, and I wonder what it would look like were I truly under a dark sky. Still, I find the progress to be really exciting. Just last night, I learned that Unistellar had released yet another software update: this time to enable planetary observation. I couldn't resist, and marched back to the same field. This time, however, I was a little disappointed. While the telescope for the first time automatically dimmed its images of Jupiter and Mars and showed real details on both worlds, overall the view was of course radically different from what I see through my refractors. While traditional telescopes may not as clearly reveal the cloud bands of Jupiter, for example, they show far finer and subtler detail; far more realistic and impressive coloration; and of course the moons and stars surrounding the planets.

I expected as much, but in the moment I couldn't help but be underwhelmed. Yet while walking home, I considered where the technology might be in another two years. Eventually, I suspect there will be few if any areas where traditional telescopes reign supreme. To me, their greatest value could then lie in the connection they provide to generations of observers stretching back to Galileo: to a history of often-eccentric women and men straining at odd hours to discern barely perceptible truths hidden across unimaginable distances in time and space. There are some things clever software can never replace - not many, perhaps, but some. It was Father's Day yesterday, and I had sanction to wake up late. When I found out the night would be clear, I was full of anticipation - until I realized that seeing was forecast to be about as bad as I can remember. I stepped out after sundown, however, and found the stars unusually visible in the night sky. Sure enough, transparency was high above average - which made sense, as the night as unusually crisp for a DC summer. Out I stepped at around 1:30 AM, burdened like a Tolkien dwarf with the EVScope II on my back, and a tripod in hand. This time I walked to a nearby school's soccer pitch, which not only affords an impressive view of the whole sky but is also (strangely) bereft of street lights. I set up in a few seconds, then targeted the heart of the Milky Way as it rose well above the southeastern horizon. The light pollution is very bad in that direction - it's right above the National Mall - but still, I had high hopes. I've largely praised the EVScope in these pages, and rightfully so. In a matter of moments the Omega Nebula emerged from the background light pollution, and wow that is an impressive effect. After a five-minute exposure, I moved on to the Lagoon Nebula, with much the same results. I now slewed to the Owl Nebula, but this time the view underwhelmed - even after five minutes - and it's not surprising: at around tenth magnitude, it's a challenge for the EVScope in light-polluted skies. As the chill began to set in, I finished up with the Sunflower Galaxy: a faint spiral roughly the size of the Milky Way, 27 million light years distant. It was a subtle view after six minutes or so, but still recognizable. I had profoundly mixed feelings as I walked home. On the one hand, it continues to amaze me that the EVScope brings nebulae and galaxies within my reach, from downtown DC. On the other - and this can't be stressed enough - using the telescope is not comparable to traditional observing. With a regular telescope, the bulk of your time is spent straining at the eyepiece. You train yourself to see like observers have for centuries - using averted vision, for example - and there's an art to it that you can improve over time. When you're not observing the obviously spectacular - Saturn or the Moon, for example - then what's visible through the eyepiece can be absurdly subtle. The average person would never recognize, let alone appreciate, what you can just barely glimpse. What makes it special is the sensation of seeing with your own eyes what can otherwise be admired only in enhanced pictures. You are truly experiencing the universe, albeit only as well as imperfect optics and a turbulent atmosphere will permit on any given night. With the EVScope, by contrast, you navigate an app on your phone. You stare at a screen as the telescope effortlessly targets and then observes your chosen object for you. Slowly, a picture emerges of the object you've selected. It's a little like a picture you can Google - something taken by Hubble, for example - except way worse. As the picture slowly brightens, you wait. You scroll through other stuff on your phone, perhaps, or you sit there thinking. One thing is for sure: most of the time, you aren't actually looking at space at all. Eventually, you turn your attention back to the app and if you're satisfied enough with the picture, you target something else. You end up with pictures that look impressive when they're small, on your phone, but - owing to their resolution or the unavoidable influence of light pollution - underwhelm when you blow them up on your laptop.

It's exciting to find what's out there, in the sky, that you could never see with traditional optics (barring a difficult-to-use astrophotography setup, of course). But sometimes, walking home, the experience leaves you cold. Sometimes, you feel like all you've done is played with screens. You haven't really experienced nature, and you certainly haven't learned an art. Everything was easy, so occasionally it feels like little was gained. You might as well played with a screen at home. On some nights, the EVScope can feel like a toy - whereas a more traditional telescope always feels like a tool. Maybe that's because of how and where I'm using the EVScope. Maybe the telescope could do more under a darker sky, and certainly the EVScope comes with citizen science features that I haven't begun to access yet. But with the similarly-priced FC 100DZ, for example, I feel like I'm engaging in an old art with a rich history. With the EVScope, I often feel more like I'm playing a game on my phone. Both have their virtues, but if I had to choose one telescope - it would be the refractor. The sky was that beautiful, robin egg blue yesterday, and sunset faded into an equally clear night. Seeing and transparency were both well above average, so I thought I'd take the TEC 140 out again to have my first look at the Orion Nebula since the spring. Sadly, the hour lost with the daylight saving time adjustment means that the bright planets are now too low in the night sky by the time I can make it out of the house; I'll look for them again in the spring. By midnight Orion was well above the horizon, with Sirius right behind, climbing up out of the glow of the National Mall. After a few minutes telescope and eyepieces acclimated to the crisp evening air. When they did I took out a 10mm Delos eyepiece, and was delighted to find that I could clearly make out six stars in the Trapezium (Theta-1 Orionis) - the little star cluster at the heart of the Orion Nebula - without using averted vision. I've never been able to see the E and F stars so clearly, and I was especially impressed because they were still emerging from the worst of our DC light pollution. The green-blue glow of Orion billowed around those stars, of course, with plenty of nebulosity dimly visible (this time with averted vision) even well beyond the brightest arc of the nebula. As usual, the effect was mesmerizing. Under an urban sky, Orion may be the only nebula or galaxy that looks better through one of my refractors than it does through the EVScope. With a 24mm Panoptic eyepiece I could observe just about the entire sheath of Orion's sword, with the nebula at the heart of it - truly a sublime view. It was getting late by the time I'd had my fill of Orion, so in spite of myself I decided to forego looking at any of the beautiful double stars in the sky right now (except Rigel, an old favorite). Instead I turned to the Andromeda Galaxy, just to remember what it looked like from the city with a truly top-tier refractor. It was a dim blob, of course; no match for what electronically assisted astronomy can reveal. But still, as always a thought-provoking sight.

The march home was painful and exhausting - I had to stop a couple times along the way - but still I was happy to have the season's first view of Orion. Next time with the EVScope, I think. Another clear night on the Atlantic Coast, again with good seeing (but mediocre transparency). Once again I quickly set up my EVScope, and this time I had eyes on the galaxies in the Big Dipper, towards the north, and the Nebulae around the galactic core in the south. The galaxies turned out to be a little disappointing, partly because the EVScope's "enhanced vision" - its image-stacking mode - kept cutting out after just a few minutes. I've had a spotty and unpredictable wifi signal here, which might be to blame. Light pollution is also worse towards the north, and the Big Dipper was low on the horizon. The nebulae to the south, however, were nothing short of spectacular. Below (clockwise from top left) are the Lagoon, Omega, Trifid, and Eagle nebulae, in five- to 10-minute exposures. What really strikes me is the amount of subtle detail in each of these short exposures, especially the dark lanes weaving through each nebula. I took all of these shots, collectively, in about 30 minutes - and then packed up my telescope in around 10 seconds. So, another successful night here in Lewes, Delaware. Now it's back to our light-polluted skies in DC, where my next targets will probably be Jupiter and Saturn.

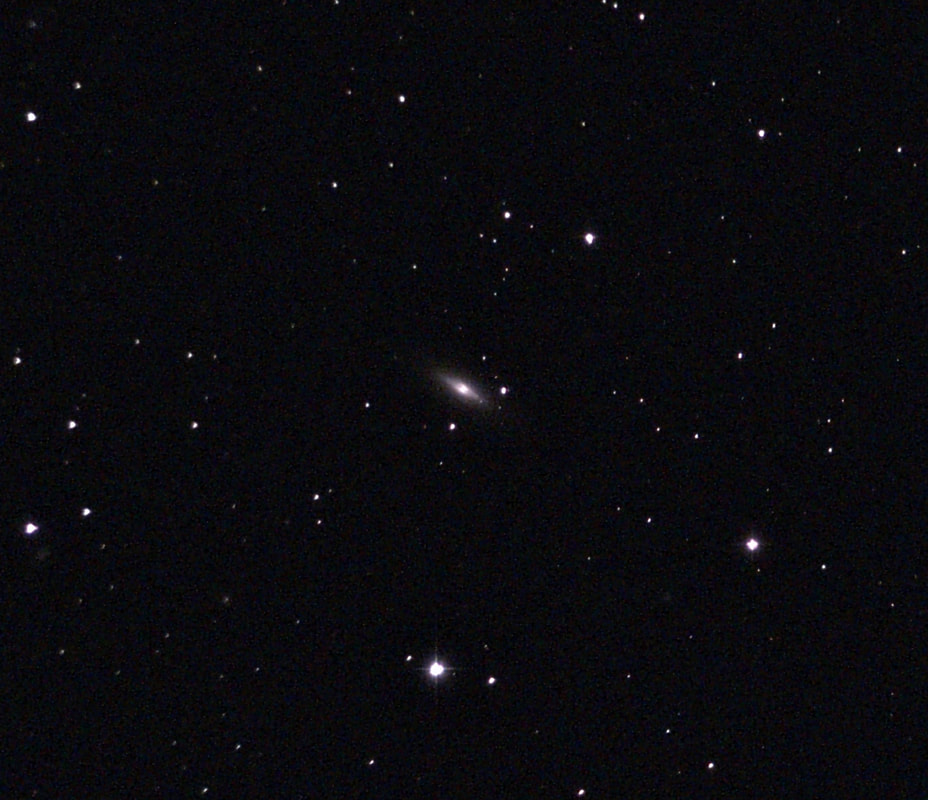

I've written about the EVScope and Electronically Assisted Astronomy (EAA) quite frequently in these pages. I was skeptical at first - partly because my EVScope had a technical problem - and only came around slowly. Only last night did I become an enthusiastic supporter. I stepped out on a warm, breezy night with the EVScope in its backpack. Transparency and seeing were both around average; there was no Moon. When I reached our nearby park, I set up in all of 30 seconds. I decided that my first target would be the Eagle Nebula, which I've never glimpsed through a regular telescope. The galactic core was lost in light pollution over the National Mall - the sky seemed closer to white than black - so I wasn't optimistic. And yet! When the EVScope found its target - in just a few moments - and started gathering light, a multitude of stars snapped into view, and then the nebula. After a couple minutes, light pollution started to cloud the view - I haven't tried to tinker with the settings that could help me resolve that issue, not yet - so I stopped the exposure after eight minutes or so. I was left with this: In the dark, on my phone, it looked spectacular. Look! There are the pillars of creation - star-making factories so memorably imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope - somehow visible from downtown Washington, DC, just nine or so minutes after setting up in an urban park. This image does it for me - I like my nebulae ghostly and ethereal - but with a little image processing, even more detail pops out (see the picture at the beginning of this post). Now it was on to the Trifid Nebula nearby, it too lost in downtown pollution. Not for long! Again, I'd never seen it with a regular telescope, yet again, it didn't take long to pop into view through the EVScope. This image I like a little less; the unprocessed version doesn't quite bring out the blue. Still, getting this detail so easily in the middle of a city feels nothing short of miraculous. Then it was off to the Ring Nebula which, of course, never fails to impress - albeit in very different ways through an optical versus an EAA telescope. Whether because of a software update or an unusually transparent sky - I suspect the former - I was, for the first time, able to see the white dwarf at the heart of the nebula. Seeing that would require an enormous regular telescope - too big for my car - and a very dark sky. Imagine my wonder at glimpsing the dead star from the city: our Sun's future, six or seven billion years from now. I didn't have much time left, but I wanted to see how far I could reach. I turned to NGC 5907, a galaxy marginally larger than our own, around 54 million light years distant. I could only take a short exposure - I really did have to leave - but there: an edge-on spiral galaxy that I would never have been able to observe even with my TEC 140. The light in this picture left its source not only after the dinosaurs went extinct. What a thought!

I packed up just as quickly as I set up, and then a pleasant walk home with my backpack. It is simply remarkable to see so much so easily. I've often seen the EVScope's hardware discussed and praised, yet what really stands out to me is the software. If only other mounts, carrying regular telescopes, were so easy to use. On November 16th, the sky was clear and, after a glorious sunset, atmospheric seeing promised to be mediocre but transparency was predicted to be superb. With no Moon in the sky, conditions were right to take the EVScope for another spin. I've now (separately) purchased the backpack that's sold with the EVScope; my rolling case, I suspect, my knock the telescope out of alignment. When I set it up this time, collimation was just about perfect. I made a couple tiny tweaks - again, this took seconds - and then rapidly achieved fine focus with the built-in Bahtinov mask. It was cold and I was exhausted, so I figured I would only take two ten-minute exposures of the Andromeda and Triangulum galaxies. Moments after the telescope slewed to Andromeda, I heard some rustling in the distance and noticed a dim orange glow, appearing and disappearing. Then the sounds of muttering wafted over on the breeze. It seemed I was sharing my park - and I had the disquieting feeling that I was being observed. After about eight minutes or so, I thought a third shadow joined the two in the distance, and then the rustling got closer. The conversation, it seemed, was definitely in Russian. Suddenly a flashlight turned on; there were three people, and they were walking directly towards me. I greeted them: "Hello? Hi!". At that, one of them exclaimed "oh my God!", and then all three of them darted to the side, behind a bush, and disappeared. The sounds receded into the distance. That was unsettling. Fortunately, after ten minutes the Andromeda exposure turned out nicely, considering the light pollution. Collimation and fine alignment really makes for much tighter stars and far better images, though I imagine things would be better still in superior seeing (and, of course, under a darker sky). Now it was on to Triangulum. It wasn't long ago that I managed to spot the galaxy with the FC-100DC, under darker skies some distance from DC. I noticed only a slight brightening of the sky, with averted vision, in what I could just perceive - or imagine - to be a spiral pattern. Clearly observing the galaxy now, from downtown, is a particular thrill. I don't know why, but Triangulum in particular has always captured my imagination. Maybe it's because it gets so little attention compared to the two giants of our Local Group of galaxies, or maybe because it's a face-on galaxy with distinctly knotted spiral arms . . . I'm not sure why, exactly. In any case, I find that the EVScope does a particularly good job on this galaxy (see above). And again, during the exposure I was in for a shock. With a loud thump and a lot of growing, a rabbit suddenly rushed right by the telescope, a fox in hot pursuit. The fox stopped short of my location with a snarl, then scampered - its little legs a blur - over a hill and behind a bush. Both fox and rabbit were no more than six feet from me. I couldn't wait to tell my four-year-old daughter in the morning. Anyway, after a few more minutes the Triangulum exposure was done to my satisfaction. I packed up the telescope, warmed my chilled fingers, and walked home. Suffice it to say, I've really started to enjoy the EVScope. A few days after my strange night with the EVScope, an ad appeared on AstroMart that forced me into hours of tortured thought (usually while attempting to get my one-year-old to sleep). Here was a Takahashi FC-100DZ, used only once and in pristine condition. As I've mentioned before, this year I've been tempted to swap my 100DC for a DZ. The DZ has better color correction and its optics might be marginally sharper, on average, though both improvements may be difficult to detect visually (I read many opinions, and they seem to differ). You can read a great breakdown of the relative merits of the four current FC-100 models here. I've resisted the urge to swap the DC for the DZ because, first, the hassle and expense seemed daunting, and second, the DC's weight is supposed to be lighter. The difference in weight, I concluded, outweighed (sorry) the marginal difference in optical quality. Yet the four-inch refractor is my most used telescope, and now I couldn't resist the urge to upgrade to maybe the finest refractor of this size ever made. So, I bought the DZ and sold my DC (along with some other stuff to make up the cost). I have to say, the comparison between DC and DZ surprised me in a few ways that aren't covered elsewhere. First and for my purposes most importantly, the weight difference between the two telescopes is scarcely noticeable. In the above pictures, you can see the DZ in a configuration for short-range, daytime viewing. However, to reach focus for astronomical viewing you must detach one of the couplings, and that makes the DZ noticeably lighter. It is then also more compact than the DZ when the sliding dew shield is tucked over the optical tube. Second, the most important couplings of the DZ do not screw apart but rather use thumbscrews and compression rings. You can also use that system to attach a diagonal, and I can't tell you what a difference it makes. I actually detest the Takahashi fetish for stacking screwable couplings in the visual back. The couplings, I've found, tend to stick together, and they're not wide enough to grip easily. It's easy to damage them (cosmetically) by applying too much pressure (I did as much to one of the DC's couplings). The new system brings the DZ in line with most other fine refractors, and it is just such a relief. Third, to balance the telescope - using just about any eyepiece - the clamshell tube holder must sit farther from the visual back than it does with the DC. This may seem like a very minor detail, but it provides more room for a red dot finder (RDF) just in front of the visual back. My Rigel QuikFinder RDF is now in a more comfortable position, and it's those little details that can make a real difference in the field. Fourth, the focuser is just a bit nice. Its knobs are metal - not plastic, as in the DC - and the feel is a bit smoother (though I did need to adjust the tension knob for my big Delos eyepieces). I sold Takahashi's two-speed focuser upgrade with the DC, and although I will no doubt miss the fine focus on the DZ, I didn't like how the two-speed add-on left some daylight around the gear housing. On the DZ, I'll stick with the stock focuser. That focuser, by the way, allows me to reach focus with all my eyepieces - something that was just out of reach for the DC. Finally, although the sliding dew shield is very smooth and easy to use, its tightening screw does leave a subtle mark on the optical tube that is noticeable when the dew shied is deployed. I wonder if the previous owner tightened the screw a bit too much, but I doubt it; I think this is just a natural consequence of the technology. It only matters if you're obsessive about the condition of your equipment - but Takahashi telescopes are so beautiful that they tend to bring out that obsession. Last night, and against my better judgement, I took out the DZ for the first time. I say "against my better judgement" because transparency was mediocre and seeing was poor. It's a recipe for disappointment to take out a new telescope in such conditions. I couldn't resist, but I did set up near the cathedral, closer to my house so I could hurry back if observing disappointed.

And did it? Well, a look at Mars did clearly reveal that the atmosphere would not be my friend tonight. And yet, I could plainly make out no fewer than three large dark albedo markings, along with that brilliant south polar icecap. Turning elsewhere, Rigel A and B were laughably easy to split in the poor seeing, and Orion was beautiful even before it emerged from the light pollution near the horizon. So could I make out an optical difference between the DC and DZ? Not after one night of poor seeing. Mars did seem a bit yellower than it does through the DC, and certainly I could detect absolutely no hint of false color in or out of focus. I'm excited to study the Moon, for example, on a really good night. Yet I don't expect a large or even a plainly noticeable difference. I bought the DZ primarily so I could be absolutely sure that the optical quality of my most-used telescope would never hold back my observations - and so that I would never wonder what something would look like with a slightly better telescope of the same design. It's a tiny thing, but after a while tiny things start to matter a whole lot in amateur astronomy. It was a cold, damp night when I stepped out with the EVscope and found a relatively mud-free corner to set up in my park. I decided to try my hand at collimating the telescope to see if that might tighten the stars in my pictures, and I hoped to decide, once and for all, whether to keep the telescope before my refund period ran out. To my surprise, the telescope was badly out of focus when I turned it on - so out of focus that its auto-alignment failed. Fortunately, it comes with a bahtinov mask cleverly built into the dew shield. Achieving rough focus, and then fine focus with the mask, takes a matter of seconds. With that done, the telescope immediately found alignment, and I got it to slew to Bellatrix, a fairly bright star in Orion. Now I turned the focuser knob until a dark cross appeared in front of the suddenly bloated star: the spider vanes holding up what would be a secondary mirror in most reflectors (but is a sensor in the EVScope). The cross was badly askew, which means that the telescope was poorly collimated. It took all of 30 seconds or so to fix the problem, and even less time to achieve fine focus again. And then, voila: the stars were more closely to dots - rather than smeared blobs - and the resolution of the telescope suddenly seemed higher. Funny how that works. I tried my hand at imaging a few objects: the Orion Nebula, of course, and the Flame Nebula, Bode's Galaxy, and the little galaxy NGC 1637. The latter was a bust: it's very small, and lost in the glow of light pollution to the south. An unavoidable problem for me is that the EVScope amplifies both the light of deep space objects and the light pollution in our DC skies. It's not a problem for brilliant objects like the Orion Nebula or the Andromeda Galaxy, but dim, diffuse objects are another story. I also didn't take exposures longer than five minutes. It's one thing to gawk at the Moon or Mars for that long - or much longer - but another thing to sit silently in the cold, waiting. But was it ever cool to see the spiral arms of Bode's Galaxy, slowly brightening on my screen as the minutes and seconds ticked by. Here were photons 12 million years old, from a galaxy nearly the size of our own, somehow visible in an urban sky. The view was quite sharp, I thought, and the telescope performed perfectly, immediately slewing to whatever I asked it to find.

Do I prefer my optical telescopes? Yes, for most objects I do, but it's simply true that the EVScope shows me hundreds of nebulae and galaxies that I never imagined seeing from the city, and reveals glorious detail in wonders I thought I already knew well. It's a keeper. Now if only I could get a lightweight, go-to mount for my refractors . . . . |

Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed