|

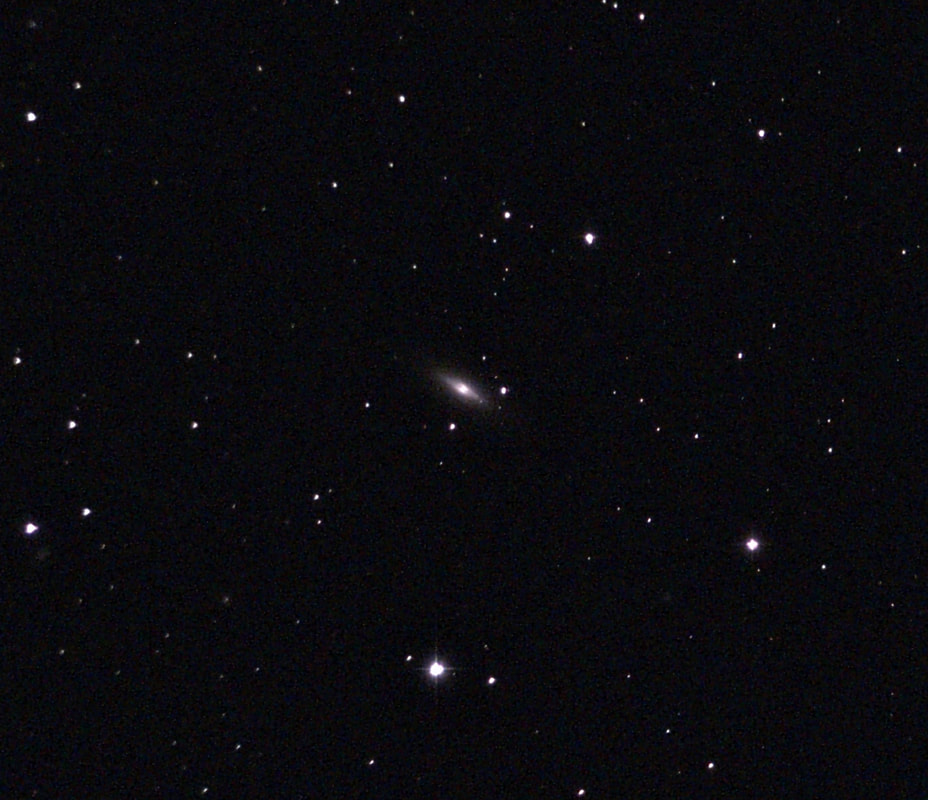

Recently, I've been on a mission to optimize my grab-and-go setup. Slowly but surely, parks that offered dark corners for a telescope have been saturated with bright lights: the kind that needlessly waste energy, confuse nocturnal animals, and pollute the night sky. I have to walk further than I have before, or settle for less than ideal observing conditions. To that end, setups that used to feel perfectly mobile now are discouragingly cumbersome to use. I admit I was tempted to swap my FC-100DZ for a lighter telescope, such as the FC-100DC I used to have and love. Then I had an epiphany - one I should have had long ago. With its diagonal removed and dew shield retracted, the DZ is just over two feet long. Couldn't I find a padded bag that long? If so, the DZ would be as easy to transport as my dearly departed TV 85, while offering considerably better performance. I found the bag - for just $23! - and wow: what a difference. It's strange but true: the DZ is as transportable as much smaller telescopes, but offers truly stunning views of everything that shines through light-polluted skies. The other night, I pointed it at Saturn, which is just now reaching opposition (its closest annual approach to Earth). The view was spellbinding, with glimpses of detail in the planet's clouds that were among the finest I've seen. On the other hand, DC's summer mosquitoes did not give me a moment's rest, and I was grateful that my little setup takes just a few minutes to disassemble. Then, last weekend, it was off for what has become an annual trip to the beach near Lewes, Delaware. I brought my EVScope 2, eagerly anticipating darker skies. Unfortunately, I soon found that atmospheric transparency was lower near the beach than it has been in years past - owing, once again, to that wildfire smoke. Worse, my recent experience with a truly pristine sky in Manitoba left me unimpressed with the view in Delaware. Sure, the Milky Way was barely, and I mean just barely, visible after fifteen minutes outside in the dark. But there was simply no comparison. I occasionally fantasize about selling my EVScope in exchange for a more capable astrophotography setup. The three (!) clear nights I experienced in Lewes reminded me why I have that fantasy - and why I haven't acted on it yet. First, the telescope needed collimation. If you've read any reviews of the EVScope, you'll know that some complain about the need to collimate such an expensive gizmo. Let me assure you that it's much easier than collimating an SCT, for example. Even when the telescope is badly misaligned - as it was for me in Lewes - the entire process takes a few minutes at most. The real problem is that Unistellar's instructions include a glaring error. To collimate the telescope, it should not be pointed at a particularly bright star - I tried Antares - because the star's brilliance will not allow you to see the secondary mirror when out of focus. I suppose it's a minor detail, but this little mistake can create a lot of frustration. Usually, it takes just moments to align the EVScope and get it ready to slew to any object you can imagine. Usually. On one night in Lewes, I had to turn off the telescope a couple times before it aligned itself. On two other nights, it did not precisely center objects after finding them - so that, at the telescope's highest magnifications, objects were simply offscreen. On a third night, everything worked seamlessly. I carefully leveled the telescope, collimated it, and waited over thirty minutes for it to acclimate. That may not sound arduous to veteran amateur astronomers - but it's hardly ideal for a grab-and-go setup. When the telescope is aligned, it tracks objects seamlessly. The trouble is that its altazimuth mount cannot perfectly track stars on long exposures. This isn't visible while peering into the eyepiece, but it does show up clearly in astrophotographs taken with the telescope. Since most people will use the telescope by staring at their phones or tablets - in fact, some Unistellar models don't even have eyepieces - this is a serious limitation. Even this six-minute exposure of the Eagle Nebula has distorted stars. Stars are also distorted - even through the eyepiece - because stars shimmer in all but the steadiest atmospheric conditions. When using a traditional telescope - especially a refractor - you may see a roving, flickering pinpoint. Yet the EVScope takes exposures to provide its bright views of deep space objects, and in these exposures the undulating pinpoints that are stars in mediocre seeing all congeal into blurry blobs. For a refractor aficionado like myself, the effect is deeply unsatisfying. To me, it really does not feel like you are actually peering into space when you use an EVScope. Occasionally I wonder: what am I getting here that I could not obtain by finding images on the internet? Have a look at this shot of the Wild Duck Cluster, for example. The problem is compounded by the reality that Unistellar's software cannot quite compensate for the effects of light pollution. Overall, it does a remarkable job - I'm still amazed that I can admire the Triangulum Galaxy from downtown DC, for example - but there's still a good deal of noise even under a Bortle 4 or 4.5 sky (as in Lewes). Have a look at this 24-minute exposure of the Pinwheel Galaxy, and notice the noise. Another inconvenient truth is that, even with the galactic core above the horizon in the summer, there just aren't that many objects that truly impress when viewed with the EVScope. You have to remember that although the EVScope allows you to view galaxies and nebulae that are far beyond the reach of a comparably-sized traditional telescope, it is also incapable of providing satisfactory views of many objects that such a telescope would reveal. Open clusters, double stars, the Moon, and the planets: everything that impresses when seen through a telescope like the Takahashi FC-100DZ is underwhelming at best when viewed with the EVScope. In practice, dozens of objects in the EVScope's catalogue look like this, and hundreds are far less impressive. The EVScope also seems to have a weak wifi signal. Walk twenty feet away, and you're likely to lose it. You can forget about sitting indoors while operating the telescope. That's too bad, because mosquitoes really can make it hard to stay outside in our muggy summers. In other places, winters are just too cold for comfortable observing. Wouldn't it be easy for Unistellar to include some way of amplifying the wifi signal on its $5,000 device? So yes, I was getting a little annoyed in Lewes. I kept imagining what my TEC 140 might reveal; not nebulae in a distant galaxy, sure, but pinpoint stars on a velvety black background, and spectacular planetary views. This is the best that the EVScope can do on Jupiter, even after a recent software update that dramatically improves planetary performance. I admit: I could go on. Suffice it to say that my nights in Lewes reminded me that, if you buy an EVScope, you really should go for the EVScope 2. This is because the eyepiece is really a lot better than some reviews suggest. Somehow, images of nebulae and galaxies are much brighter and sharper through the eyepiece than they appear to be when viewed on a phone or tablet. The distortions I complained about above - those blurred stars, in particular - are also minimized when viewed through the eyepiece, likely because the small scale of the image mitigates them. As a result, I am consistently impressed by the nebulae and galaxies I see through the eyepiece; so impressed that I take an image that then disappoints. Just before I took the image of the Pinwheel Galaxy that you've already seen, I invited my wife and our friend outside to have a look. Both are astronomy novices, to put it mildly. Both seemed skeptical that they'd see much. Yet when both craned over the EVScope eyepiece, they gasped. They could not believe that they had seen a whole galaxy across 20 million years in time and space. They kept saying how cool it was. "It's almost like one of those picture slide viewers," my friend eventually said. Indeed. You see so much more - and so much less - than you would with an ordinary telescope. That is why I think I'll keep the EVScope . . . for now. Here are some extra images, showing medium-length exposures of some of the best-known sights in the summer sky.

0 Comments

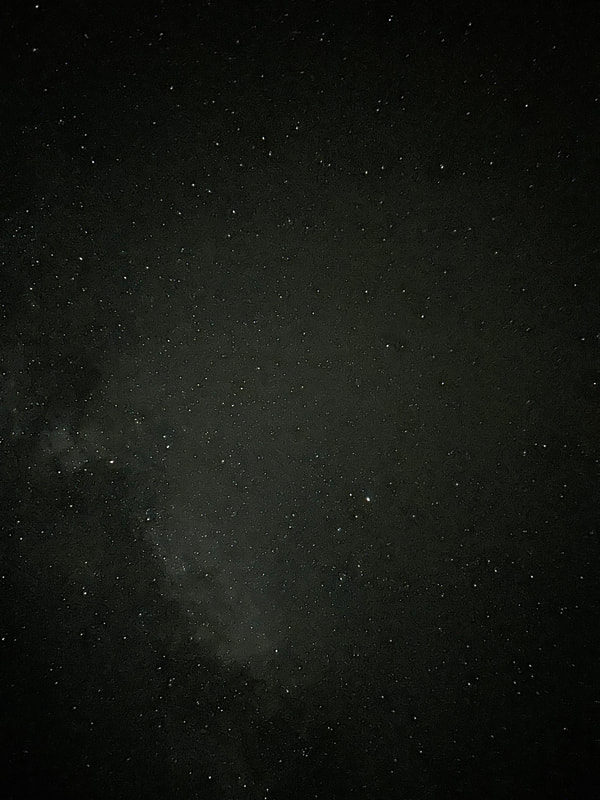

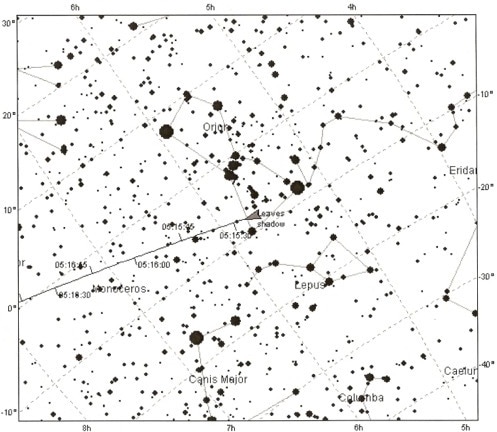

Last week, we made what used to be an annual pilgrimage to Riding Mountain National Park, a 3,000-kilometer expanse near the border of Saskatchewan and Manitoba. Home to one of North America's largest populations of black bears, the park boasts a Bortle 1 sky: the darkest you can find on planet Earth. One of the greatest wonders I've experienced in amateur astronomy was that night sky, some ten years ago. I convinced my then girlfriend - now wife - to join me on a drive down a gravel road, flanked by dense forest. We stepped out in a clearing and oh, that sky. Our eyes weren't fully dark adjusted, but there was the Milky Way, boiling with exquisite clarity across a truly coal-black background. And the stars! I remember being stunned by their vivid colors: blue, red, yellow, and white, gemstones strung across the galactic core. Then we heard yips and yelps in the darkness, from the other side of the road - coyotes? Wolves? We dashed into the car. Unfortunately there are just a lot of animals in Riding Mountain that can kill a human, and most come out with the stars. There's a large pack of wolves (I stumbled across one of their kills once, complete with fresh paw prints), a host of lynx, plenty of bobcats, a healthy population of coyotes, a smattering of cougars, and more than a thousand bears - to say nothing of big herbivores that don't like to be startled. Most - all? - can see better in the dark than humans can. There wasn't enough room in our van to pack my Winnipeg telescope, but still: this time, I was determined to have a longer look at the sky. Things got off to an inauspicious start when, at about 10:00 PM on the first clear night, I nearly walked into a giant black bear near our cabin. It ran off into the undergrowth, the branches swaying and cracking as it disappeared. I hurried back to safety. I consoled myself with the knowledge that a thin haze of wildfire smoke would have dimmed the stars. The next night was perfectly clear, however; mercifully, the smoke had drifted east. I steeled myself and, at midnight, crept out of my cabin. It was dark - I could barely make out my hand in front of my face - but I knew roughly where I was going. When I got to about 50 feet away from the cabin, the dread started to set in. Yet my eyes were adapting to the dark, and to my delight I could start to make out the Milky Way. I inched forward, and at about 100 feet away I could clearly discern the galaxy arcing from one horizon to the next. What a sight! But closer to Earth, I couldn't see a thing, and my fear was getting hard to manage. Every noise, I was sure, was a predator creeping closer. I hurried back inside, and yes I was relieved to close the door. On the following night, the sky was again perfectly clear. This time, I lingered nearer my cabin, but I set up my phone and captured a ten-second exposure of the sky - then another, and another. You can see the results above. Yet they don't quite capture what the view was really like, beyond the glow of the cottage lights. It filled me with awe to see the Milky Way with such clarity - and, if I'm honest, profound regret at being sequestered in a big city. What I wouldn't give to live under a truly dark sky! Ralph Waldo Emerson famously wrote that: "If the stars should appear one night in a thousand years, how would men believe and adore, and preserve for many generations the remembrance of the city of God!" That resonated with me. Nearly all of us have lost the true wonder of the heavens: the humbling perspective of our impossibly immense galaxy, with its countless Suns and Earths, stretching around and above us. Catching a glimpse now and then is the best we can hope for - and indeed, what an impression it then makes. Things clouded over by morning, but the view scarcely worsened. We drove out to join the bison, and they put on a show. But of course, I couldn't stop thinking about the night sky on the pre-Columbian plains. I'm not sure historians have begun to process what it meant for us, as a species, when most of us lost that view. At least these bison still enjoy it.

|

Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed