|

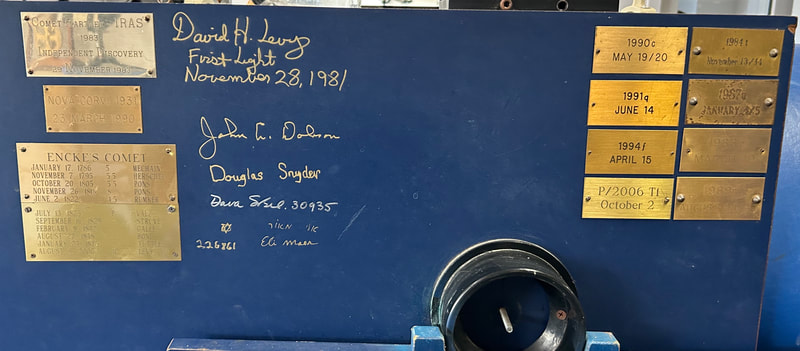

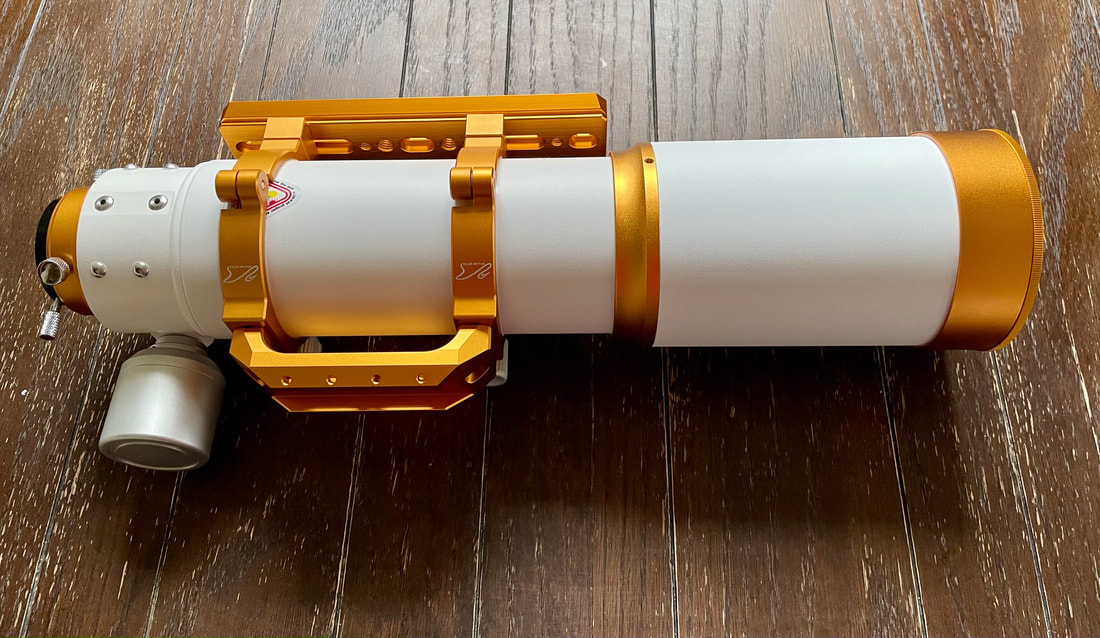

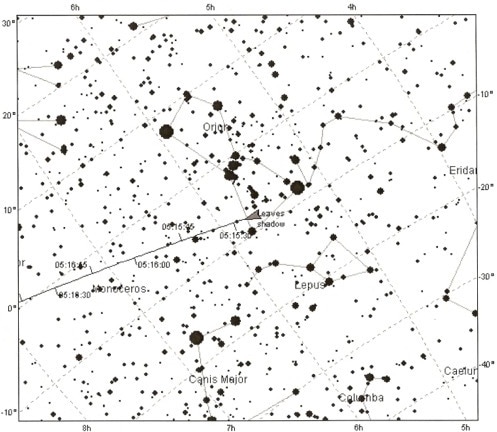

It was midnight on September 1st, and the atmosphere was about as good as it gets for stargazing here in Washington, DC. Transparency was high, seeing was great, Saturn was high in the sky and Jupiter was wheeling over the horizon. My had prepared my TEC 140 in the living room, and prepared to haul it outside. I knew I'd have to walk for a few minutes, and I tried to figure out how best to do it. The telescope itself is just over 20 pounds. The DM-6 mount that holds it well? With its extender, also just north of 20 pounds. The Planet tripod that keeps it all stable? Another 27 pounds. With my eyepieces and including all the cases and bags that house the gear, I was looking at hauling more than 80 pounds. That might have seemed doable were it not for the size everything took up. I simply could imagine no way to drag my gear to my only nearby observing site in fewer than two - possibly three - walks. It had been a long day at work, and I was still tired from recent travels. I left my gear in place. There would be other nights. The next morning, it dawned on me that something was out of whack. Since my little backyard faces north and is usually too shrouded by leaves to be useful for astronomy, I need to be able to easily transport my gear to a more suitable spot. Last year I bought a wagon to make that easier, but dragging it around turned out to be nearly as difficult as carrying my equipment. Given my need to walk to observe, I'd long ago decided that my heaviest telescope would be a medium-sized refractor, and the TEC seemed like the best option available. Somehow, however, I'd ended up with a heap of gear that was almost impossibly heavy to walk with. What happened? Well, it turns out that in amateur astronomy - as in many other things - a sufficient number of little changes can collectively create a new paradigm. The trouble was that the TEC 140 is just a bit heavier and (especially) longer than a medium-sized mount can handle, and that required a big, hulking DM-6. Both DM-6 and TEC 140 are also just a bit too heavy for a medium-sized tripod, especially on a hard surface. Enter the Planet tripod. A medium-sized telescope therefore required gear that was heavy enough to hold something much larger. Yes, it was beautifully stable once set up. But that didn't mean much if it was too massive to move. With a heavy heart, I put my TEC 140 up for sale. Within hours, a friendly local buyer had scooped it up. While I was, on some level, sorry to let it go, it also struck me that I'd made few genuinely special memories with it. I tend to grow attached to instruments that have genuinely shown me something new. My dearly-departed TV 85, for example, revealed just how much sharper a refractor could be in our DC weather than any other kind of telescope - and gave me my first unambiguous view of the Great Red Spot. My Takahashi FC 100DC gave me truly unforgettable views of Mars, and the shadows of Jupiter's moons. My APM 140 gave me even more stunning views of Mars and Jupiter, and then the 100DZ left me breathless while gawking at the Moon. The TEC 140 did give me a wonderful sensational of texture in the Jovian clouds. But that wasn't quite enough to build a bond. After I sold my now-useless DM-6 and Planet tripod, I had some decisions to make. Should I downsize by, for example, buying a jewel-like Questar 3.5? I opted it against it after reading convinced me that the iconic little telescope could simply not compete with the also-portable 100DZ. I opted to attempt to buy two lighter but still medium-sized telescopes that I hoped could largely replace - or even improve upon - the capabilities of the TEC, while requiring a much lighter tripod and mount. The first of those telescopes: a TSA 120. Takahashi's four-inch refractors have long been my favorite telescopes. I decided to try something a little bigger in the five-inch TSA 120, an air-spaced triplet (a refractor with three lenses) that, I thought, could gather meaningfully more light than the 100 DZ. I'd long resisted buying an air-spaced triplet, since these telescopes weigh more than doublets and take much longer to cool down. The weight of the TSA 120, however, splits the difference between the TEC 140 and 100 DZ, and I figured I could simply let it acclimate in my backyard before carrying it to a more suitable observing site. To my delight, I managed to buy the TSA 120 on sale. When it arrived, I was immediately surprised by its compact size. Although its aperture is just a bit lower than that of the TEC 140, its dimensions seem closer to those of the 100DZ than the TEC 140. I also had not expected it to ship with a quality two-speed focuser. You can purchase the telescope with the bulkier but ostensibly more precise Feathertouch focuser, but Takahashi's equivalent is, to my mind, just about as good. Truth be told, I don't really understand the obsession with replacing the focusers on premium telescopes, like the Takahashi refractors. All you need is something that gets the telescope in focus, and to my mind the stock focusers do that very well. It's a small point and one I've brought up before, but still: I can't get enough of the Takahashi aesthetic. The white tube, black trim look is classic for a reason, but here's to doing something a little different. I think Ed Ting once mentioned that Takahashi telescopes have an indefinable Zen character to them, and that feels about right. It makes me inexplicably happy to see them. That's not to say that the build quality of the TSA 120 exceeds that of the TEC 140, but I do prefer that cream-colored paint with mint-green accents. Anyway, on September 14th the sky cleared and temperatures cooled just after I'd finished setting up my new TSA 120 (with Moonlite tube rings courtesy of a very helpful veteran of the Cloudy Nights forum). By then, I'd found that my Berlebach Uni tripod and (wonderful) NoH's Mount CT-20 easily support the TSA 120, which made for a setup that weighs about 40 pounds total - half as much as the TEC 140 and its equipment! I bought a Stellarvue C9S case for the TSA 120 that fits it exceptionally well, and I left the telescope outside, in its case, for about 40 minutes before using it. This time I easily walked to my nearest observing site, in the courtyard of my building. Saturn is just about a month past opposition, and high above the horizon at about 11:00 PM. I decided that its light would be the first that entered my new telescope. I have a strange relationship with Saturn. To me, it's still the most impressive object in the night sky. Yet as a target for repeat observation, it pales in comparison to Jupiter and Mars. Its rings change their tilt over time, sure, but I can rarely make out enough detail on its disk to give me the impression that I'm viewing an evolving world. Well, the TSA 120 might change that. At about 90x with my Delos 10mm eyepiece, Saturn was spectacularly well defined. I'm not sure I've ever seen such fine detail in the grey clouds above its rings. The outline of its rings was razor-sharp, the Cassini division clearly outlined. It was, I decided, about the best view I've had of the planet. Mosquitoes started to emerge, whining near my ears, but I was so distracted that I soon found myself covered in bites. I packed up and walked back home - easily. When I got inside, I was a little taken aback. I wasn't sure exactly how my view of Saturn compared to the best I had with the TEC 140; almost exactly two years ago I marveled in these pages that the bigger refractor gave me an "absolutely stunning" look at that planet. And yet, I couldn't say while unpacking the TSA 120 that I'd ever had a better view of Saturn. The sharpness is what most impressed, and the collection of bright little moons, swarming around the planet like moths around a lantern. Granted, both seeing and transparency had seemed better than average. But if the TSA 120 gave me a view that left me so satisfied, why had I hauled around so much more weight for so long? On September 15th, the pellucid evening sky invited another round with Saturn. This time, I brought out the second telescope I'd purchased: a Mewlon 210. These unusual Dall-Kirkham telescopes are a little like condensed Newtonian reflectors, with very long focal lengths. They cool down more quickly than other catadioptric telescopes - like the ubiquitous Schmidt–Cassegrain - and have none of the dew problems that can hamper these telescopes in a humid environment (Washington, DC certainly qualifies). Takahashi makes its Mewlon variants to exacting specifications, and that should in theory make them exceptional planetary telescopes. They are famously tricky to collimate, however, and they must be perfectly collimated to realize their potential. They also take a lot longer to cool down than (smaller) refractors, and their field of view is much narrower. They are much more sensitive to poor or mediocre seeing than those refractors, and the vanes that hold their little secondary mirrors produce faint rays around bright objects. The Mewlon is, therefore, a specialist instrument. Yet when conditions are right, all Mewlon variants are designed to give spectacular views of the Moon, planets, and double stars: precisely those objects I most enjoy observing in the city. At over eight inches in aperture, in good seeing the Mewlon 210 should in fact reveal those objects with even greater brightness and detail than the TEC 140. And - remarkably - it weighs much less than that telescope, despite looking much heavier. On that note, I will add that, in my view, the Mewlon 210 is quite possibly the most impressive amateur telescope to look at. It is simply beautiful. It looks like a jet engine crafted with care by a Swiss clockmaker. What's more, it comes complete with a finder scope that stays perfectly aligned with the telescope, and is so robust that you can use it as a handle. You may have to collimate the telescope from time to time, but you never have to align the finder - and that makes up for a lot. So how did the Mewlon perform on Saturn? Sadly: not as good as the TSA 120. It was clear from the box that the telescope had been handled roughly on its way to me, and something - or someone - had knocked it out of collimation. All the same, it was only a little off, and I hope I can tweak it to perfection sometime soon. Maybe in my backyard, after the leaves finally fall? Remarkably, atmospheric seeing and transparency were again above average last night, so I stepped out again with my TSA 120. This time, I waited until about midnight, when Jupiter had climbed above the horizon. I turned to Saturn first, and now the view was truly breathtaking: slightly but meaningfully more vivid - more crisp - than I'd seen even a couple nights earlier. I quickly switched to a 4.5mm Delos, giving me a magnification of exactly 200x. In my experience, Washington's sky rarely allows that kind of power. Yet to my astonishment, the atmosphere repeatedly settled down to allow a remarkably sharp view at that magnification. The subtle mingling of grey, beige, and buttermilk threads in the planet's atmosphere was simply a joy to tease out, and I could make out glimpses of structure in its ring system that I'm not sure I've ever seen before. Was this my best-ever view of Saturn? I concluded that it probably was, and again I was so enthralled that I lost track of the mosquitoes biting me. Eventually I wheeled the telescope around to Jupiter, and now the view was a little softer. The planet was still climbing out of (Earth's) thicker atmosphere near the horizon, and seeing seemed less stable in its corner of the sky. Still, I routinely made out wonderfully delicate detail in its many belts and zones. It's a little silly to compare the view through different telescopes on different nights, and perhaps sillier still to compare exceptional refractors to one another. Yet even (or perhaps especially) the most unscientific comparisons are fun, and in this case I think they're instructive. On my nights of observing, I judged that the TSA 120 showed just a bit less contrast - on Jupiter especially - than the TEC 140, and perhaps the APM 140 I once had. Yet it showed more contrast than the 100DZ - the planets seemed just a bit more vibrant - and the views were just as sharp; sharper than anything I could remember seeing through the bigger refractors. I was particularly impressed by how easily the TSA 120 snapped into focus, and how readily it gobbled up magnification. On both fronts, it seemed to exceed the performance of any telescope I've tried using. Now, all the usual caveats about the atmosphere certainly apply, but that's the point. When telescopes get to a certain quality and size, it's often factors beyond the performance of their optics that are most important. I truly did love my TEC 140. Yet I can't conclude that it's superior to the TSA 120. Both telescopes have brilliant optics that, in Washington DC, are almost invariably limited by the atmosphere, rather than their innate capabilities. Yet a setup that supports one telescope is fully twice as heavy as the other. When you're tired at the end of a long day, it doesn't take much to discourage even a quick observing session. With that in mind, the lighter, more portable setup is more often the best one. At least, it seems like it is for me. I know this is a long entry, but I can't conclude without mentioning a recent trip to the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada archive in Toronto. Since I was last there, the society's staff have set up several dozen telescopes that had me feeling like a kid in a candy store. There were two beautiful Unitron refractors, an exceptionally long Antares achromatic, a huge Cave reflector . . . the list goes on. But one in particular stood out - the ugliest one, by a long shot. Yes, that's David Levy's trusty telescope: a makeshift Dobsonian reflector complete with duct tape and what looks like a jar (!) over a finder scope. Plaques commemorating discovered comets line its base like kills on a Spitfire. Here was a poignant reminder that the best telescope - or indeed the best machine of any sort - is the one that works for you, and you alone.

2 Comments

Often, around this time of the year, the unstable atmosphere of winter yields to the more settled air of spring in Washington, DC. With the mosquitoes a month or two away, now is the time to observe as much as possible. The planets are all lined up at sunset, but unfortunately that part of the sky is obscured in all my nearby observing spots. Instead, for two nights over the past week, I've enjoyed a world much nearer our own. Today the sky was a beautiful, deep azure, and tonight's forecast called for good seeing with fair transparency. I decided conditions were good enough to exert a little more effort than usual. I hauled out my TEC 140 - now on a hulking Berlebach Planet tripod - and found a nook not far from my backyard. At this time of the year, budding leaves are just beginning to make my backyard unusable for astronomy. Turning to the Moon, I was disappointed - if not exactly surprised - to realize that the forecast had, again, gotten it wrong. Seeing seemed mediocre at best, and the atmosphere had that soft, milky quality that often frustrates planetary and lunar viewing. As my eyepieces and, to a lesser extent, my telescope cooled down, the atmosphere between me and the Moon started to stabilize - or, rather, it started dip into fleeting moments of clarity. Especially compelling in these "revelation peeps" - using Percival Lowell's terminology, as I've mentioned in an earlier entry - was Schickard crater, the massive walled plain clearly visible towards the center-right of this picture: Schickard's crater floor - that walled plain - was alive with irreducible detail, including countless tiny craterlets. As Eugene Shoemaker established at the dawn of the Space Age, the layering of lunar features provides a roadmap to their age. Signs of bombardment on the floor and walls of a big crater provide clear evidence that the big crater is very old. Of course, the little craters scattered around the big crater would have formed long after the big one. I love looking at the Moon as a geologist might, and I am always especially drawn to features on which observers have reported transient lunar phenomena (TLPs). Influential amateur Patrick Moore, for example, reported what seemed like a mist over Shickard just before Hitler's army invaded Poland in 1939. This time, however, all was crystal-clear. It was not my first lunar experience of the week. Several nights ago, I stepped out with my most portable setup - the Takahashi FC-100DZ on a photographic tripod - because atmospheric conditions were forecast to be mediocre at best. I'm glad I did! After I set up - with only my Baader variable zoom eyepiece in hand - I turned to the Moon and realized that, in fact, seeing was far better than average. Have a look at the picture above. Comparing it to the picture that begins this entry will reveal that, for amateur astronomers, the state of the atmosphere can be so much more important than the capabilities of a telescope. The first image was taken by a telescope that costs well over twice as much, and gathers more than twice as much light, as the one that provided that second image. Yet the second image is clearly far better. Here's a close-up of my favorite stretch of the Moon: the wonderfully diverse landscape winding from Plato (top) and Vallis Alpes down through Mare Imbrium to Archimedes, Erastosthenes, and finally spectacular Copernicus, here largely enveloped in shadow. Many of these features - or environments, as I prefer to think of them - have a rich and often bizarre history. Across some three hundred years, scientists compared them to features on Earth, speculated about their supposed inhabitants, tracked their alleged changes, and finally explored them through the voyages of crewed and robotic spacecraft.

Just look at the extraordinary detail the little Takahashi reveals - and remember that, as usual, this is an iPhone picture that blurs what is visible to the naked eye. Honestly, if you're into lunar exploring, you don't need more than a quality four-inch refractor. Tonight was one of those relatively rare wintry nights in Washington, DC, where atmospheric transparency is high while seeing is better than average. With Mars just four days away from opposition - its biannual closest approach to Earth - I couldn't let the opportunity slip. The canopies above my backyard are now sufficiently denuded for me to use a telescope just a few steps from my door, so out I stepped with my TEC 140. The Moon was just about to slip behind my building, and I was hard pressed to get a quick picture. The view was in fact beautifully sharp, what you see above is the only shot I could get. I also managed to get a quick look at Jupiter, where to my surprise it seemed that one moon - near the limb of Jupiter - was far below the orbital plane set by the other moons. I don't think I've seen that before. Eventually, I found a comfortable nook from which to observe Mars. Seeing seemed a good deal better than average tonight, and the outline of the planet was about as sharp and steady as I've ever seen it. I was struck by how much smaller it seemed than it did during its last opposition, two years ago, when it looked only marginally smaller than it did during its perihelic opposition of 2018. Of course, my gear has improved since then, so the views of Mars I've had this year haven't been much worse than those I had in 2020. Still, the planet's apparent diameter is only about 17 arcseconds this year - down from 22.4 in 2020, and a whopping 24.2 in 2018. In fact, not since 2014 has Mars looked so unimposing at opposition.

More important for viewing Mars than the apparent size of the planet or my equipment, however, has been dust. In 2018, I couldn't make out any details on Mars while using my Skywatcher 100ED, and that owed more to a yellow, planet-wide dust storm than the lack of perfect color correction on the refractor. In 2020, Mars was relatively dust-free, and so a deeper shade of red. I was ready then with a pair of telescopes (my dearly departed APM 140 and Takahashi FC-100DC) that were only slightly less capable than those I own today. Now Mars seems dusty and a bit yellowish again, but not as much as it was in 2018. Surface detail has obvious through my TEC 140 and Takahashi FC-100DZ, though not as much as it was in 2020, and the planet's disk is comparatively small. I replaced my APM 140 with the TEC 140ED, and my FC-100DC with the FC100DZ, in large part to prepare for this year's opposition. I'm glad I did, but in making those replacements I've also come to realize that there really are rapidly diminishing returns for costly upgrades in this hobby. Yes, views through the DZ seem marginally better than the ones I enjoyed with my wonderful DC, but from night to night conditions in our atmosphere - and that of Mars - are much more important. Tonight I was again reminded of how trifling differences in performance between optics can be enormously exaggerated in online discussions. It's widely held that high-contrast eyepieces such as the TeleVue Delos will easily outperform zoom eyepieces, including the latest iteration of the Baader Hyperion Zoom. While switching between the zoom eyepiece and the Delos 4.5mm and 6mm eyepieces, however, I found that magnification affected the view far more than the eyepiece I was using. The view seemed just right at around 160x; any more than that, and it got a little blurry. Both the Baader and TeleVue eyepieces provided striking and at times rather complex views of Mare Cimmerium at that magnification, along with flashes of Trivium Charontis and perhaps some other dark regions in the northern hemisphere of Mars. I thought I might have caught some hints of white swaths far to the south, but they were hard to pin down; I fancied they might be clouds. I saw very little to separate the eyepieces, but I eventually found myself settling with the 6mm Delos because of its larger field of view. If pressed I might confess that dark albedo regions were more consistently obvious in the Delos than the Baader Zoom - but that may be only because I expected to see them more clearly in the Delos. One thing's for sure: I'll never again assume that I'm missing out by using the zoom eyepiece as opposed to a Delos, and I'll be a little more careful when reading claims that one premium eyepiece or telescope is clearly superior to another. I hope to have another chance to observe Mars this week, and certainly this month, but if not tonight was a wonderful way to mark the planet's opposition. Autumn came early this year in Washington DC, yet the relative warmth of early autumn lingered well past its usual expiration date. The mosquitoes lingered with it, even if their population fell with the leaves, but overall it's been a gorgeous month in the city. Over the past week, we had three crisp, clear nights with tolerably good seeing and transparency. With the canopies above my yard increasingly bare, I was able to peak through and branches and observe without hauling heavy gear for twenty exhausting minutes. A few nights ago, I rolled out my TEC 140 to observe the Moon and Jupiter. Night comes early at this time of the year, of course, so I made it outside before my six-year-old daughter's bedtime. I asked her to join me, and when she did she was thrilled to make out craters on the Moon and, with some difficulty, cloud bands on Jupiter. To my surprise, those were unusually difficult to make out. The sky had a milky quality around bright objects, a kind of watercolor softness, that seemed to obscure detail on the likes of Jupiter. Still, a memorable experience for daughter and daddy alike. On November 8th, conditions promised to be marginally better, and temperatures were just about ideal. This time, I stepped out with a much lighter setup: my Takahashi FC-100DZ, clamped to the CT-20 mount that I'd screwed into my Berlebach Uni tripod. It's a more robust outfit than I take to the local park, but it's still easy to move all in one go. A quick aside: the exceptional weight of the DM-6 mount can make it really sturdy and capable of handling surprisingly hefty telescopes. Yet it also ruins the portability of my TEC 140. The mount feels at least as heavy as the telescope, and when yoked to a tripod it's a chore to move even without the telescope attached. Another problem is that attaching the telescope to the DM-6 mount is a heart-stopping experience in the dark. It's hard to be sure that the dovetail is actually in the clamp, and I've now been unpleasantly surprised several times when the telescope suddenly lurched down after I thought I'd got it in. I live in fear that on some sad night I'll misjudge it, step away, and watch in horror as the telescope crashes to the ground. I have no such problem with the Takahashi. Yet the lightness of the CT-20 mount does mean that the telescope tends to tilt - even when perfectly balanced - if objects are too close to zenith. The CT-20 has an answer, however: it's easy to adjust the tension in the altitude and azimuth axes. This can mean that there's too much tension to easily nudge the telescope along when observing objects that are high up in the sky, but I'll take the tradeoff: less weight and less hassle is worth some compromise. In any case, the Takahashi gave me some very satisfactory views of the waning but still nearly full Moon. The view along the emerging terminator in particular was quite striking, while the Moon's fully illuminated surface showed a mesmerizing swirl of subtle grey shadings. The rays streaking from Tycho, one of the youngest big craters on the lunar surface, are always impressive when the Moon is this close to full. Yet Mars is now wheeling towards its biannual opposition, so of course it stole the show. The planet is quite high in the sky by around 10 PM EST, and it's already brighter than any celestial body visible at that time save Jupiter and the Moon. I feel that its color even by naked eye is not quite as blood-red as it was two years ago; it's paler and a little closer to orange. The Takahashi revealed its waxing globe, but showed considerably less contrast than I could make out a couple years back. In moments of good seeing I could make out the south polar icecap, and then a dark albedo swirl around the ice, interrupted by lighter land before continuing towards the north. Yet the view was anything but sharp, and the planet seemed unsteady somehow in the mediocre seeing. Part of the problem is that much of Mars is currently obscured by bright dust storm: a common if frustrating occurrence when Mars makes a close approach to the Sun. It was to gain a clearer view of the Moon and Mars that I stepped out last night with the TEC 140. Conditions seemed about the same, except it was colder and the reappearance of a halo around the Moon suggested that transparency would be lower. The TEC takes meaningly longer to cool down than the Takahashi, although in both cases the Delos eyepieces take longer to acclimate than the telescopes. I'm not sure it's widely understood that compound eyepieces take longer to cool down than, say, Plossl eyepieces - but that's certainly been my experience, and it does stand to reason. There's just a lot of glass in those things.

In any case, both refractors and their eyepieces need only a few minutes to give acceptable views, even if they do take longer to fully acclimate. When everything was ready I was surprised to find that the TEC 140 actually provided slightly softer views than the Takahashi did the other night, even if contrast on Mars in particular seemed just a bit higher, and the Moon's terminator at times snapped into exquisite if fleeting focus. I was once again impressed by the Takahashi; despite its compact size, I rarely feel I'm missing out when I use that telescope, the way I did with many other small telescopes I've owned. It punches far above it weight. Yet to me the bigger takeaway was that the difference between telescopes is often completely swamped by atmospheric conditions. In mediocre seeing and transparency, there really isn't much of a divide between the $8000 (!) TEC 140 and the $3000 Takahashi (of course both telescopes have world-class optics; even in bad seeing, I would suspect a meaningful difference between them and a run-of-the-mill refractor). In my years of observing here in DC, I can probably count on one hand the nights on which the atmosphere was so stable and clear that I could use magnifications of 200x or more. The pricey difference between optics is often less apparent here than it would be elsewhere, and I think that's something observers should acknowledge more often. Where you live will dictate the gains you get by spending more on bigger and fancier telescopes. William Sheehan - who publishes some of the most engaging books on the history and practice of planetary and lunar observing - writes that as an observer views Mars near opposition, "over it, intermittently, uncertain details dart and then are gone like doubtful visions." None other than Percival Lowell - a key popularizer of the Mars canal theory, among other things - coined the term "revelation peeps" to describe these sudden glimpses of intricate detail. That is precisely what Mars had on offer tonight. It wobbled and wavered, like a coin seen through the burbling water of a fountain. Then, for fractions of a second, it snapped into sharp relief, looking really and truly like a planet seen from an approaching spaceship. Just before my brain could grapple with that new reality, the planet reverted so quickly to an indistinct blob that I could scarcely believe it had ever been otherwise. Mars! Always so difficult, but oh so compelling. The planets are all lined up in the early morning sky, and the summer atmosphere here in DC can really settle down at night. The Sun begins to rise at around 5 AM, however, so getting up early enough to see the planets means sacrificing sleep. Still, I couldn't resist setting out twice, over the past few weeks, to catch glimpse of Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. First, on June 25th, I marched over to a nearby soccer field with my Takahashi in hand. Seeing with supposed to be better than average, while transparency was a little worse. When I set up, however, I realized that the atmosphere was actually surprisingly turbulent around the eastern horizon. That kept me from getting a good view of either Jupiter or Mars, which was quite disappointing given how tired I was. When I swung the refractor over to Saturn, however, I realized that the atmosphere was better towards the south. I had a really nice, crisp view of the planet and its rings before wisps of high-altitude cloud convinced me to pack up. A few days later, I celebrated my daughter's sixth birthday. While hauling stuff to her party, I realized that a little wagon would really help. It also dawned on me that a big enough wagon could carry my TEC 140, together with its tripod, mount, and eyepieces. I pulled the trigger and bought a UIDYGGD Folding Wagon, hoping that I could use it to haul my biggest telescope to a nearby field. In summer the leaves are just too thick, and the streetlights are just too bright, to use the TEC 140 in or near my backyard.

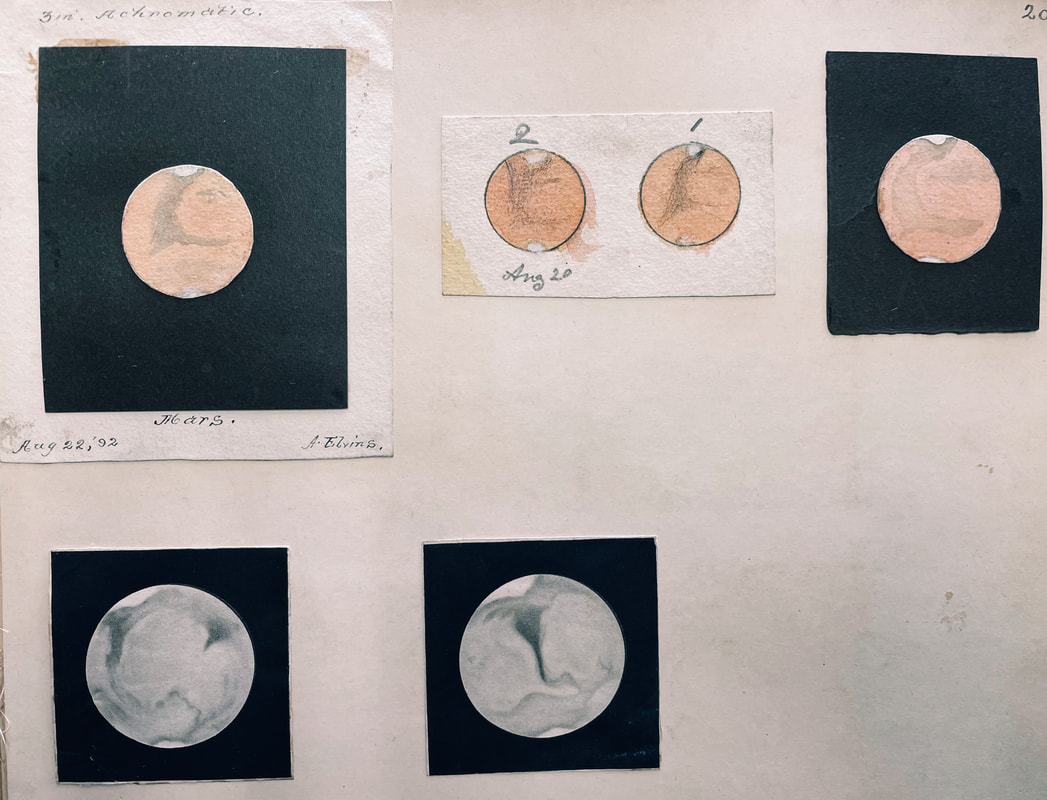

On the early morning of July 11th, I loaded everything into the wagon and began to wheel it towards the field. After about thirty seconds of hauling, I nearly gave up. I was dragging everything uphill, and my back was on fire. I paused, then persisted - and after fifteen minutes, reached the field. It occurred to me that there was no way I could have made it there while holding my telescope case in one hand, and pulling my rolling suitcase - which stores my tripod, mount, and eyepieces - in the other. After I set up, I turned to Mars and was rewarded with easily my best view of the planet this year. Not only was the south polar cap clearly visible, but so was a latticework of dark albedo features spidering up towards the planet's equator. Turning, to Jupiter, I was delighted to see the shadow of a Galilean moon, just beginning to emerge onto the planet's western limb. This time seeing really was better then average. It seemed there were more cloud belts than I could easily count, and there was that sensation of infinitely intricate detail that the clouds can have when Earth's atmosphere is sufficiently stable. Saturn, however, again stole the show. I've never had a view of Saturn using the TEC 140 that was quite as good as those I've enjoyed of Mars or Jupiter. But this time, with Saturn fairly high in the sky, I was treated to perhaps the sharpest view I've ever had of the planet. Not only was the Cassini Division plainly visible for the entire length of the rings, but I could make out multiple rings - which is rare for me -and the shadow of the rings on the planet was a perfect, velvet black. I also made out a whole slew of moons, and beautifully detailed, turbulent clouds on the planet's creamy yellow-white disk. It was a view that fully justified my lack of sleep - in fact, one of the best views I've ever had of a planet. I usually prefer viewing Jupiter and Mars to Saturn, because the appearance of the closer planets changes much more than that of Saturn. But when the atmosphere cooperates, the night sky offers nothing more beautiful - or more hauntingly alien - than Saturn and its rings. Summer has truly begun in DC when the forecast calls for back-to-back nights with good seeing, and the planets begin to rise high above the horizon. After a very satisfying morning with my Takahashi FC-100DZ, gazing at the southern icecap of Mars, I hauled out my TEC 140 last night and found the same gap in the trees. Once again, there were Mars and Jupiter in the pellucid morning sky, in good (if not exactly great) seeing. I'd swapped my DM-4 mount for a DM-6, and my carbon fiber tripod for a Berlebach Uni. The heavier ensemble is much more pleasant to use. As I've written in these pages, there's just not beating the mechanical quality of TEC. Every aspect of the 140 is a joy to see and a pleasure to manipulate. The DM-6 and Uni hold the telescope exceptionally well, with virtually no vibrations even when I adjust the buttery-smooth Feathertouch focuser. If I could have just one setup: yes, it would be this. I've often found an easily noticeable difference at the eyepiece between quality 4- and 5.5-inch refractors. The TEC in particular has given me my finest-ever views of Jupiter and the Moon, with an ethereal, three-dimensional quality and the sensation of texture that I've never had with another telescope. This morning, however, I was mildly surprised to find that the view resembled what I'd seen the previous morning, using the FC-100DZ. Granted, I could see a star near Mars that I hadn't sighted with the smaller refractor, and the cloud belts of Jupiter definitely showed more detail in moments of steady seeing. At well over 200x, a dark albedo feature on Mars seemed to more clearly extend north from the southern icecap, which of course I could make out clearly. Yet the difference was, overall, insubstantial. I think amateur astronomers too often exaggerate the importance of equipment in what they can discern at the eyepiece, and too often understate the influence of the atmosphere. In my experience, even subtle atmospheric differences from night to night - and from one part of the sky to the other - can matter more than very substantial differences in equipment (that might make one setup cost many thousands of dollars more than another). It's humbling to know that a $150 telescope - such as the C90 - could outperform an $8000 refractor (such as the TEC 140) on any given night. I also wonder to what extent nearby streetlights were running interference, softening the view at the eyepiece. Something like that seems to have happened to me before, when my FC-100DC suddenly showed garish chromatic aberration as I observed the Moon under some bright lights. In any case, several dark markings - barges? - were fleetingly visible in what I took to be the north equatorial and north temperate cloud belts of Jupiter. I was again struck by the pale and almost washed-out view of the planet, where contrast has often seemed so stark with a 5.5-inch refractor. I thought I could make out a very faded Great Red Spot: not much more than a subtle blotch in the planet's southern hemisphere. After I packed up, I reflected on a recent trip to some astronomical archives, which I consulted to complete my next book, Ripples in the Cosmic Ocean. Among other stops, my travels took me to the archive of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, which is tucked away in a little office on the second-story of a nondescript building in Toronto. There's a heap of telescopes in the middle of the archive, and the Society's wonderful archivist explained to me that all of them, in various ways, tell the history of astronomy in Canada. He hopes to mount them in a museum - and indeed I drooled over some fascinating pieces. One I found particularly striking: a beautifully-preserved little telescope - is it 40, maybe 50mm across? - used by satellite-trackers in Operation Moonwatch, amid the paranoia that accompanied the early Space Age. The mechanical quality really impressed me - the tabletop tripod alone was a diminutive masterpiece - and I wondered what the optics could reveal. I'll bet today's amateurs would pay through the nose for a travel scope like this one. I visited the archive to look over some astronomical logbooks, and as usual those were a treat. It can be viscerally moving to read over another amateur's drawings and reflections from decades or centuries ago. Our world has changed - and sometimes other worlds have, too - but there's a common thread: the long-dead observer and I both gazed with wonder at something that's far bigger than our fleeting lives. We struggle to put in words what it means for us, as we obsess over equipment and traces of detail in planetary disks. We are the Universe, conscious of itself - but only briefly. Conditions were glorious last night - temperatures in teens, seeing and transparency both above average - and I was feeling surprisingly energetic, so I dragged my TEC 140, DM-6, and Berlebach Uni tripod out the door, and walked 15 minutes to my favorite nearby park. I had about 80 pounds of gear with me, but somehow, last night, I found it quite manageable. It was heartening to know that I could transport the TEC 140 without much more difficulty than I used to haul about my dearly departed APM 140.

When I set up shop I noticed that the sky was strikingly dark, and that the stars and planets scarcely twinkled. I immediately plugged in my highest-power Delos eyepiece - which manages 217x - and targeted Jupiter. What a view! I lost track of how many cloud belts I could make out, and subtle detail was everywhere. I was looking at the same hemisphere I had admired about a week ago with the TEC 140, and that same barge I noticed then was still around. Now the Galilean moons looked even more clearly like disks, and therefore like real little worlds. I decided that the difference between the TEC 140 and the APM 140 lies in the sensation of texture on the planets. More than the APM, the TEC gives me the feeling that the clouds of Jupiter, for example, have depth, which in turns makes it clearer that I'm observing a three-dimensional object. That really makes a profound difference. Both the APM and the TEC provide views that are far better than those of four-inch refractors, including the Takahashi FC-100DZ. There's just so much more contrast visible with the bigger refractors, and on a low-contrast object like Jupiter that means everything. The view of Saturn was a bit less perfect, just like it was a week ago. While I could easily crank up my magnification past 200x on Jupiter - which is usually about the limit in the Washington, DC air - Saturn benefitted from lower magnification. Still, I was struck by the obvious complexity of its ring system in moments of good seeing. It seemed I could clearly make out not only the Cassini division, but at times I got a flicker of brightness variations, attesting to distinct ring groupings of varying brightness. After observing Jupiter and Saturn for a while, I wheeled the telescope east to observe the Pleiades at low magnification, which was pleasant but not noticeably different than it is in a smaller refractor. Then I realized that Uranus had climbed well over the horizon, and in fact that it should now be near 37 Ari, a star of very comparable magnitude (5.75 to 6 for Uranus). I've never observed Uranus before. I've tried to find it, but come up empty time and time again. It's actually a little embarrassing; it shouldn't be that hard to identify. So, this time, with the weather perfect and armed with a powerhouse telescope, I decided to give it a try. The trick was to find Menkar (Alpha Ceti) and Kaffaljidhma (Gamma Ceti) in the constellation Cetus. While these are bright stars - Menkar in particular, at magnitude 2.5 - it's telling that even with atmospheric transparency better than average, I could only barely make them out. DC's light pollution is especially bad to the southeast from my position, which is where the national mall and the rest of the city's downtown area is located. Anyway, once I found those two stars I used them to triangulate Mu Ceti, which at magnitude 4.25 truly was at the edge of my perception. These three stars in Cetus formed a narrow triangle that pointed to Uranus and 37 Ari. In fact, the length of the triangle was actually greater than the distance of the planet from that triangle. Using my finderscope, I searched. And searched. About 20 minutes went by, and no dice: I could see only stars. I started scanning more broadly, thinking I'd done something wrong. Then I checked my star map - which I get through an app called Stellarium - and suddenly it hit me: I'd been looking for something that looked like a planet. But Uranus is so far away - and therefore so dim - that it should really be indistinguishable from a star at low magnifications. My problem was that I had plugged in my 24mm Panoptic eyepiece, which gave me a magnification of just about 40x. I needed to trust my map and really crank up the power on the star that, I knew, must be Uranus. So I did. With the high power Delos eyepiece back in and my magnification at 217x, suddenly the planet became obvious: a little grey-green ball, wandering through space. I could make out, at most, only the subtlest detail on that little ball - and really it was virtually featureless. But the thought that that ball was four times the diameter of Earth gave me a rare, visceral sense of the scale of the Solar System. It can be hard to wrap your mind around the reality that the distance between Uranus and Saturn is actually greater than the distance between Saturn and the Sun. Now, at the eyepiece, it seemed obvious. I hadn't found Uranus before because I'd underestimated the size of the Solar System; I didn't imagine that a planet so big could look so small. It might seem like a drawback of manual mounts that it took me over 20 minutes to find Uranus - not to mention the many times I've searched for the planet and failed. Nothing could be further from the truth. When you do "star-hop" successfully with a simple mount, the sensation of actually finding what you're looking for is really special, and you don't get that with a go-to mount. You also start to genuinely learn the sky; I'd never thought about the constellation Cetus, for example, but now I know where it is, and I know that its third-brightest star is actually a triple-star system that I'd like to check out someday. That's not to say that star-hopping is always feasible or desirable, especially in the big city. But, as usual, you do give something up by opting for the convenience of modern technology. A last note on equipment: in recent days, I've ranked the Delos eyepieces, TEC 140, Orion 6x30 finder, DM-6, and Berlebach Uni tripod in comparison with other gear I've used. I've described them as the best I've seen in their class of equipment. Yet I haven't mentioned how well they all fit together. It really is seamless. The DM-6 holds the TEC 140 with perfect ease; there are no jitters, just buttery smooth movement even at high magnifications. The Uni tripod, while light, is an absolute rock, while the finder scope makes it a breeze to hop between stars. And the Delos eyepieces slotted in the TEC 140 provide a glorious view of just about everything. It's all very pricey, of course, but I really recommend this mix. The walk home was arduous. But, like William Herschel exactly 240 years ago, I'd found a new planet, and that made it easily worthwhile. We've had some wonderfully clear, autumnal nights over the past week, with Jupiter and Saturn riding high in the evening sky and the Moon waxing and waning nearby. I'm teaching what may be my favorite course at the moment - about the human history of nearby celestial bodies (what I call "neighboring worlds"), and a special highlight is taking my students out for a night with a telescope. I have now accumulated some very fine refractors, however, and I worried about how they'd fare after being handled by twenty students. To that end, I drew on my research funds to buy a William Optics Zenithstar 81. It's a beautiful little refractor, and I figured that it would be more than adequate to give my students an impressive view of the Moon. For their first assignment, they need to find a feature on the Moon and then write a history of how people have understood, imagined, explored, or planned to exploit that feature. A few things immediately struck me about the Zenithstar. First, it costs about a third as much as the TeleVue 85 I used to own - less than a third, when you consider it comes with its own mounting rings, dovetail, Bahtinov mask, and carrying case - despite giving up only four millimeters in aperture. Second, its build quality looks to be on par with the very best telescopes I own and have owned, with the possible exception of my TEC 140. Third, it seems to weigh less than the FS-60Q I once owned, and much less than the TV 85, and its sliding dew shield makes it much more compact than either telescope. It was really easy to carry the telescope to a darker corner of campus, and there set it up on my DM-4 mount and Berlebach Report tripod. Almost immediately, the Plossl eyepieces I'd decided to use provided beautifully crisp views of the nearly fully illuminated Moon. The students who had started to gather were predictably impressed. When we found we had a few minutes to spare at the end of the evening, I decided to try showing them Jupiter and Saturn. At about 56x, the planets were small, but beautifully sharp and clear. Many of my students were awestruck; they had a hard time believing that they could really see the major cloud belts of Jupiter and the rings of Saturn from downtown DC. Experiential learning is always special; it makes the otherwise abstract concepts we discuss in class come alive for my students, and it can provide lifelong memories. I for one was stunned by the performance of the little refractor. It is, by far, the most portable telescope I've owned, and when it comes to performance it really doesn't give up much to the TV 85. I loved my TV 85, but I would have a hard time recommending that telescope as a go-to instrument when the Zenithstar seems to provide so much more value for the cost. Last night conditions were even better, and now I resolved to head out with my biggest telescope: the TEC 140. The weight of the telescope, tripod, and mount means that I really can't haul everything to my favorite field. I targeted the little alcove next to a church that I've used over the past year, yet when I arrived as I was dismayed to find that the church had installed a new streetlight that completely ruled out observing there. I wandered about, dragging my heavy gear, until I decided to head down to a little amphitheater near the National Cathedral. There I found a perch that, if I moved around a bit, afforded me a view of Jupiter, Saturn, and the Moon through the canopies of nearby trees. When I swung the TEC to Saturn, I was mesmerized. This was only the second time I'd used the TEC, and the first time in good seeing. In those conditions, Saturn looked absolutely stunning, like a beautiful jewel set in a velvet background. Its many moons were brilliant and sharp, and the shadow of the planet on its rings gave me the rare sense that I was actually seeing a world in three dimensions (often, objects in the eyepiece look flat, and therefore two dimensional). Cloud details were obvious on the planet's yellow-white disk. Switching over to Jupiter provided an even more spectacular revelation. The TEC provided what may have been my best-ever view of the planet, with more cloud belts and zones than I could count, delicate, feathery structures within those belts and zones, and a perfectly obvious, brown "barge" - an elongated, oval cloud feature - near the planet's equator. There was a contrast and vibrance to the planet's colors that you just don't get with a smaller refractor, and all four Galilean moons were visible as clear disks, rather than points of light. Jupiter and Saturn soon wheeled behind the trees, so it was time for the waning gibbous Moon. Once again, I was dumbstruck. The Moon wasn't that far above the horizon, but at 163x there was just such a wealth of subtle, perfectly sharp detail, from jumbled crater peaks to winding rilles and delicate scarps. The terminator was perfectly positioned to throw mountain after mountain in sharp relief, and in exploring them I eventually lost track of time. Then a giant cricket jumped on my pants, I realized in shaking it off that it was past midnight, and I began packing up for the painful trek home.

The TEC 140, I have to say, is noticeably better than the APM 140 I've also raved about in these pages. I'm not sure it's worth the extra cost; certainly I could never have afforded the difference if I didn't use the telescope for my research and writing (which means I could draw from my research funds to buy it). I realize how lucky I am, and I hope I can keep using the telescope for a lifetime. It won't be that often, however, until I manage to own a backyard; as wonderful as the telescope may be, it's also hard to transport more than a few minutes from our home. Everybody approaches amateur astronomy in different ways, but for me - and many others - the most difficult thing about the hobby is that you always wonder, no matter how sublime the view: what would I see if I had different equipment? Usually "what would I see" means "what more would I see," and usually "different" means "just a bit better" - and that means that many amateur astronomers, at least at some point, embark on a long, frustrating, painfully expensive quest for new telescopes, new mounts, new tripods, new eyepieces . . . the list goes on. I've been on that path for quite a few years now. Yet when it comes to telescopes - or more specifically, to optical tube assemblies - I reached the end this spring. For a long time, I dreamed of someday - somehow - being able to own a truly world-class, medium-sized refractor. I long had my eye on the Telescope Engineering Company (TEC) 140: an American-made, oil-spaced triplet of uncompromising optical and mechanical quality that, while portable, easily outperformed much larger telescopes. I didn't think I'd be able to afford it for a very long time, but then I realized that although I'd slowly cobbled together a rather large collection of telescopes, I was really only using three of them (my EVScope, Takahashi FC-100, and APM 140). If I sold my unused telescopes and some other gear for the right price, I might just have the financial foundation I needed to pursue a used TEC 140. Precisely as those thoughts entered my mind, a TEC 140 ED in like-new condition popped up on the used market for a daunting but reasonable price. I took the plunge, and then went on a truly exhausting campaign to sell everything I could spare to recoup what I'd spent. Some of what I sold, I know I will miss for a long time. I ended up parting with my FS-60Q, TV-85, and APM-140, and each loss stings in a slightly different way. I've had unforgettable memories with the TV-85 and APM-140 in particular, but upgrading equipment is not for the sentimental. In the end I earned precisely as much money as I spent on the TEC 140, so my guilt was mostly assuaged when it arrived. Comparing it to the APM 140 was instructive and ended up highlighting the virtues of both telescopes. The TEC 140 is, first and foremost, slightly but meaningfully heaver and bulkier than the APM 140. Its focuser is more robust, its finish is of clearly higher quality, and its tube ringers are easier to manipulate. With that said, the APM's focuser is just as buttery smooth, and I actually find its sliding few shield a little easier to manipulate. It's not a tossup - the TEC 140 is clearly mechanically superior - but the APM holds up surprisingly well when you consider that it costs less than half as much (during sales, more like a third as much). Because the TEC 140 is that much bulkier than the APM 140 and uses a Losmandy dovetail that I didn't want to replace, I needed a new, sturdier mount. That's also because my AYO II mount had, after just a year, started to develop an unacceptable amount of slippage on one side. So, I scraped together what I could and purchased a DM-6 mount to match the DM-4 I purchased for my Takahashi. This, to be sure, is a beautiful piece of metal . . . but although mechanically superior to the AYO II (in my view), it's also very substantially heavier. The upshot is that my TEC 140 setup is a good deal less portable than my APM 140 setup had been. Because it's less portable, I can't take the TEC 140 to the field where I used to set up my APM. That field will be reserved for my FC-100DZ and EVScope from now on. On some level it feels like a minor loss - I had some wonderful times there with my APM - but I'm quite sure the FC-100 can pick up the slack. And I do now have the alcove, near the church by my home, that affords some fine views of the southern sky. The TEC-140 is also so heavy that I refuse to take it out unless seeing is above average. This morning, for the first time in a while, it was forecast to be. So there I was, huffing and puffing on the sidewalk at 4:00 AM, bound for the alcove and for a date with Jupiter and Saturn. Both planets have passed behind the Sun and are again high enough above the horizon to be worth a look. It was an exhausting walk, but setup was easy and quick as usual. When I turned to Jupiter, two things struck me. First, seeing was not nearly as good as advertised; that close to the southeastern horizon, it was average at best. Second, the color correction of the telescope was absolutely spot on. The older TEC 140 ED is supposed to be slightly better in longer (red) wavelengths than the newer TEC 140 FL, but slightly worse on shorter (blue) wavelengths, which should make the ED somewhat better for observing Mars and Jupiter, but somewhat worse for astrophotography. In any case, Jupiter's coloration was lovely, even if the planet's fine detail was often obscured by the turbulent atmosphere. Saturn, fortunately, was higher in the morning sky. Turning to the planet at 98x, with a 10mm Delos eyepiece installed, made for a genuine "wow" moment. Never have I seen more than a few of Saturn's moons, but now Enceladus, Dione, Titan, Tethys, and Rhea were all clearly visible. Subtle gray shading was easy to see on the planet's disk, as was a shadow just behind the rings (I love their orientation right now). The Cassini Division was plainly obvious but now around the entire ring system; unfortunately, seeing was just not good enough to see more. Once again, the color correction was sublime. After turning to some stars and observing them in and out of focus, it was clear to me that the telescope has - surprise, surprise - exceptional, beautifully corrected optics. Yet it struck me, as it did several months ago with the FC-100DZ, how much more seeing matters than optics when it comes to planetary observation. Did I see more detail this morning on Jupiter and Saturn with the TEC 140 than I would have with the APM 140? Maybe, just a little. But have I seen more detail with the APM 140 when the atmosphere cooperated? Absolutely. I'm looking forward to experiencing what the TEC 140 can do when the atmosphere truly is steady.

I suspect I will miss the portability of the APM 140, and wow that is a good telescope when you consider its cost relative to the TEC 140. Yet for me, it is important to know that the quality of my optics are not keeping me from seeing more planetary or lunar detail. With that in mind, I am very happy with my beautiful TEC. A distant goal, accomplished surprisingly soon! |

Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed