|

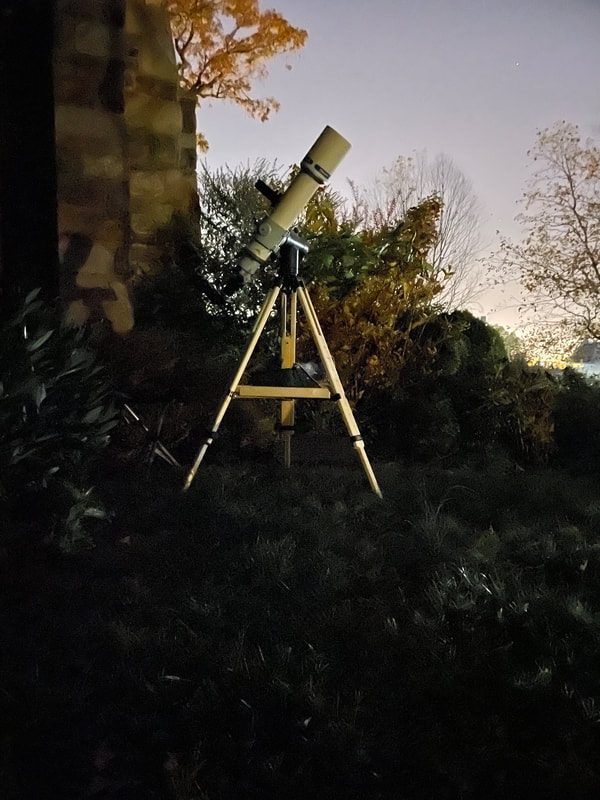

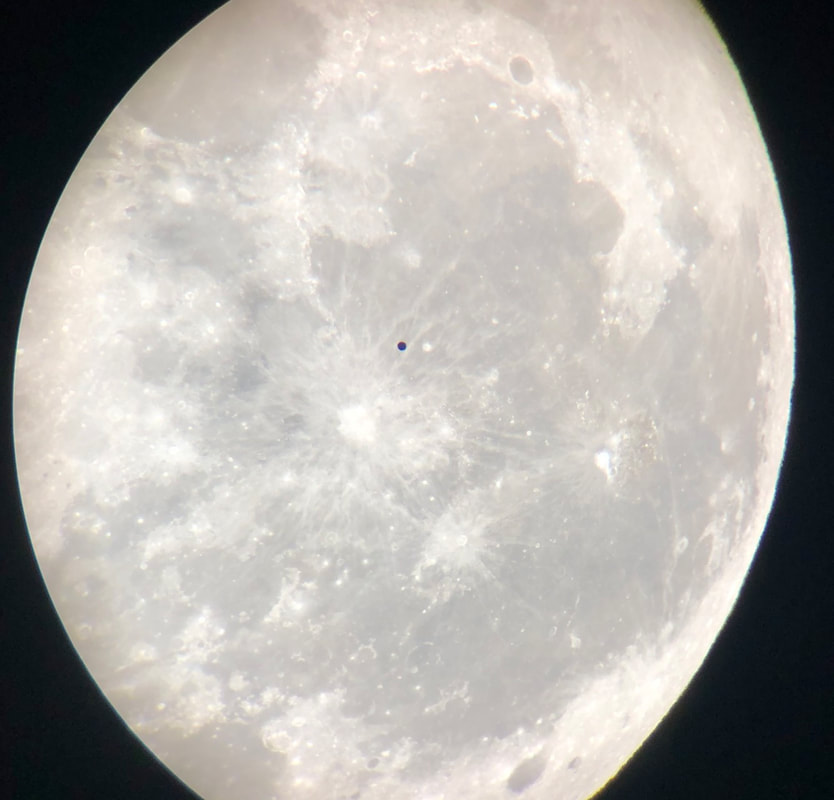

We've enjoyed maybe the best stretch of clear nights with good seeing that I've experienced since moving to Washington, DC, and I was out nearly every night with a telescope in hand. Between work, childcare, and observing, I had no chance to update this blog - but now it's raining, and I have an hour (but just an hour) to relax. Roughly two weeks ago, I spotted a Takahashi FS-102 for sale on Astromart. Amateur astronomers will know that this is a four-inch refractor with a well-earned reputation for exceptional optics. It's been replaced by the Takahashi FC-100 series, and I already own a telescope in that line. But the FS-102, while much bulkier than my 100DC, does better at longer wavelengths. And in Mars-watching season, that's what I convinced myself I needed. Although the FS-102 was supposedly in pristine condition, when it arrived I was dismayed to discover that the lens cell was loose and the tube was covered - I mean covered - with scratches. Luckily, the owner was mortified when I informed him, and I received a (nearly) full refund. I now had some cash to spare, and at just that moment a new copy of Sky and Telescope arrived. A favorable review of the EVScope convinced me to give that telescope another chance (see a previous entry for my first impressions). Maybe the buggy version I owned before had unfairly soured me on the product? It did, after all, offer me a chance to observe nebulae and galaxies I would otherwise never have a chance to see from the city . . . . After it arrived, I bundled the telescope into a suitcase and rolled it along to my nearby park. After I turned it on, it just about instantly figured out where it was and slewed (quietly) to any object in the sky, like magic. Clearly, I'd been sold a glitchy version the first time around. This was more like it! And when I tapped on "enhanced vision" (I describe the technology in a previous entry), the effect was really satisfying. After a couple minutes gathering light on the Andromeda Galaxy, for example, dust lanes I'd previously spotted only with averted vision clearly snapped into focus. So, how good are the views? Well: although I managed to achieve fine focus, I think I'll need to collimate the telescope when I'm next out. Stars are not exactly pinpoints, as these images attest, and that's also caused by a tendency of the telescope to move too much while it's gathering and stacking images. There's more noise in the pictures than I'd prefer, and after getting used to my wonderful TeleVue eyepieces, the view through the EVScope's "eyepiece" is really cramped. It's like looking through a tunnel. More importantly: no, seeing an image through a grainy screen is just not at all the same as seeing it through an optical eyepiece. An optical telescope feels like an extension of the eye; not so the digital EVScope. But damn, it's cool to see galaxies shimmer into view on my iPhone screen. It's simply true that I can see things now that I never would have imagined seeing before, and isn't that what this is all about? I mean, the Triangulum Galaxy from an urban sky . . . are you kidding me? I'm still learning how to use this technology, and pictures I've seen online tell me there's plenty of room for improvement. Still, I've noticed that the images look much more spectacular in the app, while I'm in the field, than they do after I get home. Certainly they pale in comparison to even half-decent astrophotographs made with dedicated gear. Now does the technology always work seamlessly. Just a couple nights ago, I had to restart the telescope and reinstall the software before I could get the enhanced vision mode to work, and by then I'd already shivered outside for about 30 minutes. Some objects also look immeasurably better through my optical telescopes. The EVScope is just about useless for lunar and planetary views, and stars look like ugly blobs compared to the beautiful diamonds they resemble through my refractor. Yet what the EVScope does so well is find that sweet spot between visual observation and astrophotography, and it does so in an integrated package that's usually a pleasure to use. No, I never had the thrill of seeing something with my own eyes - the thrill I've described often in these pages - but I certainly did get a deep sense of pleasure when I glimpsed the Whirlpool Galaxy from the city. One virtue of the EVScope is its weight. If I stuff the EVScope into the suitcase I used for the APM - which, admittedly, does seem to mess with its collimation - then I can easily sling my Takahashi 60Q over my shoulder (and wedge its tripod in the suitcase). I've now used the 60Q twice, including once in the early morning, with the EVScope gathering Orion's light. I have to say: I was more than a little stunned by its quality. To my astonishment, the Moon through the 60Q really didn't look any dimmer than it does through the TV 85, and details were equally sharp. Here are three images I took of the Moon over the last week, with the 60Q, the FC-100DC, and the APM 140. A reminder: the 60Q has an aperture of about 2.5 inches; the 100DC of 4 inches, and the APM of 5.5 inches (these are big differences for refractors). The optical quality of each telescope is roughly similar, though I'd say the APM shows the most false color, and the 60Q the least. That's the 60Q on the left, and the APM on the right. The comparison isn't quite fair; seeing and transparency differed on each night - it was average when I used the APM, and decidedly better than average when I used the 60Q and 100DC - and while the smaller telescopes had fully cooled down when I took these images, the APM in my judgement had not. Still, it amazes me how slight the differences are. I have a new phone, by the way, with a much better camera, and I think it shows. These pictures were taken after the APM had fully acclimated, and I think it's fair to say that now the aperture difference is more easily visible. There's a deeper and more richly textured quality to these images than there is to the 60Q closeup above. Yet it always takes me aback to realize that, when telescopes are of similar quality, differences from night to night on bright objects - the Moon especially - owe more to atmospheric conditions than anything else, including aperture. It's different for dimmer objects. I can usually see at least five stars in the Trapezium using the APM, for example, but I've rarely if ever confidently spotted a fifth with any other refractor. Mars was full of detail when I observed it with the APM - wow that south polar cap looks bright and sharply defined right now - but I found that it, and every other bright object, was surrounded by a bright halo that night. This seems to be a common and very annoying optical effect in the skies of Washington, DC. On two nights with the 100DC, however, I had no such problem. Dark albedo markings were wonderfully detailed, and I spent easily an hour both nights just enjoying the view. It's a little sad to think that every night brings us a little farther from the red planet, but the view should dazzle for months to come. One last note. My first night out with the 100DC over these past two weeks was November 3rd. I suddenly resolved to stop doom scrolling and instead do something that distracted me. But what a sinking feeling I felt, walking bewildered to the field, with panicked screams - yes, screams - echoing around me. I walked out on the 4th, too, and the mood was lighter. Then, on the 7th, while playing with my kids in the very spot I usually set up my telescopes, came the good news: the networks had called it for Biden. I'll never forget the scenes of spontaneous joy on the streets: the bells ringing, cars honking, crowds cheering. We may be in for some very dark months this winter, but that was a moment I'll long remember.

0 Comments

To say I was tired after my last morning out is an understatement. There's nothing like 16 straight hours of work and childcare after a three hour night's sleep. Yet when the forecast called for better-than-average seeing and transparency on another clear morning, I had to go out again. After all, it'll be a while before Mars looks this good. This time, however, I took my Takahashi FC-100 DC and my lightest tripod; I was still a little sore from hauling the APM. Conditions were just about the same this morning as they had been on the sixth, and that provided a nice opportunity to test how close the view through a good 4-inch refractor can get to that of a 5.5-inch (the APM). In a word (okay two words): pretty close! The Moon dazzled with detail, although I definitely saw finer features - especially those rilles - with the APM. Mars was wonderfully clear, with dark albedo features obvious but maybe a bit less dark than they had been through the APM, and the south polar ice cap much dimmer. Orion and the Trapezium were wonderful, but I could only clearly see four stars in the Trapezium - with a hint of the fifth, "F" star. You could drive a truck between Rigel A and B, but maybe a slightly smaller truck than you could with the APM. The Takahashi is just a fantastic telescope. I set out to observe Mars, and indeed I observed the planet for a good long time. Two years ago, during the last opposition, I dreamed of exactly the views I've had this year. Once again, I tried sketching the view on my phone, but it's become clear that I've reached the limit of what's possible with that technique. Next time, I'll bring sketchpad - but still, it's nice to know what I've seen. I found that the steady atmosphere easily permitted a magnification of around 250x, which is rare in these parts - and better than I enjoyed on the sixth. Although I spent a lot of time on Mars, I found I kept returning to the Moon. There's nothing like the gloriously detailed lunar views a fine refractor can reveal in good seeing. Features visible around the terminator were especially interesting tonight, with plenty of tiny craters glinting at local sunset, and some really interesting, rectilinear scarps (or so I decided; I'll have to look this up later).

So, another great morning - but it'll take me a few days to recover this time. The weather has been stormy over the past few weeks, but this morning the clouds cleared and the seeing promised to be good. I woke up at 2:45 AM and walked out the door by 3:20, hauling my APM 140. As I reached my local park, it dawned on me that conditions were essentially perfect. The sky was wonderfully transparent, the temperature was perfect, and there was a thin misting of dew on the ground. The rabbits and fireflies that used to give the park such a magical air, however, have largely disappeared (for now). It was a special morning for more than one reason. The Moon had just passed in front (occulted) Mars, and the two worlds were still right next to each other in the night sky. It was a stunning sight as I set up the APM. Then, when I wheeled the big telescope around to have a look at the Moon, I was just floored by the spectacular, razor-sharp detail. Rilles and craterlets snapped into view as I've never seen them, and I thought I could actually pick up gradations of color on a Moon that has always looked monochrome to me. It was easy to get lost in that view, but I had a job to do: observe Mars as it approaches opposition. Now, it's around five weeks away - hard to believe! - and wow does the planet look big and bright. The APM revealed it in spectacular detail, with Syrtis Major huge and dark on the planet's surface, arcing north from a south polar cap that now seems small (but bright), with Nodus Alcyonius obvious nearby. It was easily the best view of Mars I've had. By 4 AM the view softened a bit, as a turbulence entered our terrestrial atmosphere. I think I noticed a hint of the planet's rotation between 3:45 and 4:45 AM; Syrtis Major seemed just a bit offset from where it was when I set up. I knew my iPhone would never capture even a half-decent image of the view, and I kicked myself for not bringing a sketching pad. Still, I have an app called "Paper" on my phone, and I used that to quickly just down what I could easily see. An enormous amount of detail is missing, of course, including many subtle grays south of Syrtis Major. Yet I'm hopeful that I'll get better at this, and I could tell that it helped me observe more closely and carefully. By 4:30 AM or so, the highlights of the winter sky had climbed above the horizon. Of course, I had to have a look at Orion. To my surprise, six stars were visible in the Trapezium - a first for me, if memory serves. Through the APM, the nebula looked about as impressive near the light-polluted horizon as it does while near zenith with my Takahashi (or maybe even a little better). Rigel B was much easier to spot than I can remember, and the Pleiades were just spectacular. Venus, also rising in the east, was lost in atmospheric turbulence. But still, I observed its half-disk for a minute or so.

I've praised it before in this space, but wow - I cannot say enough about this APM refractor. There are times when I've fantasized about selling all my gear in exchange for an Astro-Physics refractor - something truly high-end. Yet I just can't see how the APM can be improved. I see less false color with the APM than I do with the Takahashi - even with the Takahashi's focal extender screwed in - and the detail, contrast, and color I can see on planets is just otherworldly (sorry). Bright deep space objects are a joy to observe, and the every last detail on the telescope - from the focuser to the dew shield - is a pleasure to use. Like my TV-85, there's something magical about this telescope. It's a true keeper. Also deserving of praise: TeleVue Delos eyepieces. They are, without doubt, the best I've used in terms of clarity, contrast, and comfort for my eye. Maybe I'll get another come Christmas. To put it lightly, conditions here have been far from ideal for observing. Our rooftop is now closed, following DC's lockdown order, and even going inside feels increasingly perilous (though some models suggest we may be approaching or even passing our COVID-19 peak). The weather, meanwhile, has been nothing short of atrocious, with almost unrelenting cloudiness at night, even after clear days. Tonight, the sky finally cleared up for a few hours. The astronomy forecast told me to expect better than average transparency with worse than average seeing. Since I usually specialize in lunar, planetary, and double star observing - the stuff I can do from the city almost as well as the countryside - I typically prefer good seeing over good transparency, so again it promised to be a sub-par night. Still, I had to take a telescope out before the mosquitoes come out in late spring. With the rooftop closed, I may not be able to observe comfortably for a long time when they do appear. Sadly, even municipal park is closed, too, so I was forced back to my old observing site, in a community garden with rows of plants and flowers that together create a labyrinth. Sadly, in the past two years two new buildings have popped up nearby, each with floodlights, so the spot is much worse than it once was. And even though I brought my FC-100 DC - my all-around, can't miss workhorse - on my lightest tripod, the ten-minute walk with all my gear was nothing if not uncomfortable. Still, there was Venus, just a few months from its opposition, almost comically bright in the western sky. I recently upgraded the Takahashi with a Rigel Quickfinder, which makes it so much easier to point the telescope. Within moments, Venus was in my sights. I bought a new Baader diagonal too - the best of the lot - and hoped to see a bit more of the planet than I had before. Indeed, the view was probably my best of the year, although with Venus that's not saying too much. It was quite low in the night sky, and it did have noticeable false color. Still, the seeing was actually probably above average (!), and there were moments when the atmosphere settled down enough for some sharp views of the planet and its striking cusps. I don't expect a better view this year, and wow - I even managed to get a (terrible) picture! It was atmospheric transparency that seemed far below average tonight. When I turned to the Orion Nebula, for example, the view was pretty disappointing. Orion is getting low in the night sky, and I've discovered that that makes a huge difference for its famous nebula in particular. As soon as the atmosphere gets too thick, the nebula starts to blend into the rest of the sky. Pointing to Rigel, however, I was astonished at the brightness of Rigel B and the separation I could see between it and Rigel A. It was the clearest view I've had of this spectacular star system. By then, the nearly full Moon was on the rise. It was a "Super Pink Moon," apparently, and although that doesn't refer to its actual color, bizarrely the Moon did have a pinkish hue near the horizon - a product, I suspect, of a hazy atmosphere with high humidity. Taking any pictures proved to be a nightmare. Since I can't sit in the garden, my hands and especially my legs are far less steady than they are on the rooftop. The picture above is the best I got, and doesn't quite capture the clarity of the image.

It does reveal, however, the excellent color correction on the Takahashi. I'd been tempted to replace the DC with a DZ during a recent Takahashi sale, as I mentioned below, but figured that the much lower weight of the DC made it a better bet for me - and that the visual performance would not be noticeable most nights. I felt a bit better about that decision after last night, though still: once you develop expensive eyes, it's hard not to imagine what even better color correction might be like. Towards the end of the night, a few deer nearly blundered into me, and they seemed a bit reluctant to leave when I greeted them. I kept hearing their rustling nearby. Then, I nearly stumbled across a raccoon on the walk home. With fewer people on the streets, DC's other residents seem to be taking over. Last week, it was clear for two nights in a row, with the Moon below the western horizon and all the bright planets setting soon after the Sun. A good time, I figured, to have a look at Orion - rising to the east at around 8 PM - and track down some double stars that I'd missed in years past. I've recently become much more interested in double stars, partly because I now imagine what the sky must look like from orbiting planets. On both nights, I was forced to use our observation deck. My daughter was a little sick, and I had to be on call in case she woke up and needed something. Since it's illuminated, the deck is a terrible place for deep space observation, but it's a whole lot better than nothing. Unfortunately, atmospheric turbulence was high and seeing on both nights was therefore somewhere between atrocious and worse than average. Not terrible for low-power observation of Orion and open clusters, but nowhere near good enough for splitting tricky double stars. On night one, I stepped out with my Takahashi refractor: my go-to, all-around telescope, especially in cold weather. The seeing was then closer to atrocious, especially near the horizon, and views of Orion were not exactly the best I've had. I've focused on getting great equipment, but more often than not it's the atmosphere that limits what I see at night. On top of that, it was gusty on the observation deck: gusty enough to actually push my telescope. Not a great night, to put it lightly.

Undaunted, I stepped outside on night two with both my TV 85 and my Mewlon. I observed for around 45 minutes with the TeleVue, lingering on the Pleiades and Hyades: brilliant open clusters that are now high in the sky and therefore spectacular at around 9 PM. The seeing was well below average: bad enough to notice at low magnifications, but not bad enough to spoil the view (in contrast to the previous night). After a while, I mounted my Mewlon. For over a month, I've waited for a sturdier mount to arrive from Stellarvue, but no success. I've had to cancel and go with another option, from the manufacturer of the only mount I have now: my VAMO Traveller. This mount is downright miraculous for its light weight and ability to handle substantial telescopes, but it's overmatched with the Mewlon. The view was therefore a little wobbly, and the problem was compounded but two equally bad problems: the seeing near the horizon, especially with the higher magnifications that the Mewlon permits, and the thermal state of the telescope, which had still not cooled down in the low temperatures (it was around 7° C). Stars danced in the eyepiece, or even stretched into short lines: a bizarre effect that I've rarely seen. Still, by around 10 PM, at modest magnification, I did get a decent view of Orion: a great deal brighter and perhaps more impressive than what I'd seen with the TV 85. Rigel A and B were also much easier to split with the Mewlon than with the TV 85, though I did manage it through both telescopes in spite of the awful seeing. Castor A and B also made for a brilliant and impressive binary, though, again: it was hard to find the targets I was hunting for with the opaque sky (transparency was low) soaking up DC's light pollution. In short: not the best night for the Mewlon, and exactly the kind of conditions in which the TV 85 can match much bigger telescopes. As usual: I'm still happy I stepped outside! It may be no surprise, but when I have to use one telescope these days, I take my Takahashi FC-100DC. It's wonderfully lightweight, it's beautifully made - in a way that's really growing on me - and gives views that seem remarkably bright for its aperture. By comparison, the Moon gets noticeably dimmer and yellower when I get past 150x or so in my TV 85; it stays as bright as ever at over 200x in the FC-100DC. At just after 9:00 PM on October 14, while on our observation deck with my Takahashi, I had one of the most bizarre and, for a moment, frightening sightings as an amateur astronomer. As I observed the Moon at around 150x, a perfectly black, sharply defined circle abruptly appeared in front of the white disk. It began to slowly move across the Moon, looking for all the world like a planet transiting in front of the Sun. Then, when the circle reached the edge of the Moon, it stopped and then started moving in the opposite direction across the surface of the Moon. It meandered slowly and smoothly around the lunar disk. When I increased the magnification, the circle got bigger; when I reduced magnification, it got smaller. Rattled, I checked the telescope thoroughly and found it in like-new condition, with no dust or blemishes on the lens. Eventually, I looked away from my eyepiece. When I looked again, the circle was gone. I was flabbergasted. What did I just see? I couldn't wrap my head around it. Bizarrely, I'm just now researching and writing about the history of perceived changes in lunar environments, including those often called "Transient Lunar Phenomena" (TLP). Observers who thought they'd seen a TLP in the past often expressed shock. I felt that too. The only explanation that made a modicum of sense was a balloon, at just the right distance away. But what could explain the seemingly deliberate motion of that little circle? My imagination went wild. I packed up quickly and recounted the sighting to my wife. I wrote a short report on CloudyNights, the popular astronomy forum, and then sent a message to the Central Bureau for Astronomical Telegrams. Within minutes, I received a reply from Michael Rudenko at Harvard. Apparently, I had observed one of Google's stratospheric balloons, deployed for Project Loon: an effort to bring the Internet to underserved regions. Two years ago, another sighting apparently perplexed an observer in Puerto Rico. What a coincidence - and what a reminder of just how many machines we've placed in the atmosphere, in space, and on the edge of space and atmosphere. Just before observing the Moon, I did manage to catch a glimpse of Almaak (Gamma Andromedae), the apparent double star that is really a quadruple star system. I never really got the appeal of double stars, but I'm starting to now. The contrast in colors is beautiful, as is the thought of sunsets on orbiting planets . . . .

Quite a night, overall . . . and quite a telescope. About a year ago, I picked up a Skywatcher 100ED: a "slow" (F/9) 100mm refractor. I haven't written much this year, but wow: suffice it to say, I rarely use any other telescope (and when I do, I come away disappointed). The refractor cools down quickly, throws up wonderful views, and most importantly: never gives less than optimal performance. The only drawback is the length of the tube, which makes it harder to transport and heavier to mount. This past spring, I was lucky enough to design and teach a dream course: "Mars and the Moon in science, science fiction, and society." I asked my students to join me one night to look at the moon through three telescopes: my 100ED, my older AR 102, and a colleague's beautiful, homemade reflector. Students were to find a feature on the Moon and then write about its history: not only how it was created by natural forces, but how it's been perceived, explored, and imagined by people. The night was a smash hit: lots of amazed expressions, and later, plenty of great essays. Of the three telescopes, the AR 102 was clearly a notch below - and its focuser gave us plenty of problems. This summer, Mars reached a very favorable opposition, not long after I wrote about it for the book I'm working on. When I lugged out my C8 to have a look - at around 4 AM! - it instantly (and I mean instantly) fogged over. There is nothing worse than waking up early, walking with 40 pounds for 15 minutes . . . and then having to turn right back immediately after setting up your telescope. From then on, it was all refractor, all the time. Using the 100ED, Mars typically looked like an angry orange ball, shimmering and sometimes boiling near the horizon. Yet now and then I caught fleeting and often uncertain glimpses of what I supposed to be the planet's famed dark streaks and splashes, including - I thought - Syrtis Major. I might even have made out a polar ice cap. My goal for the summer had been to see these sights with no ambiguity at all, so I came away a little disappointed. Mars is hard when it's so near the horizon. Maybe the view will be clearer in 2020 . . . and maybe I'll have even better gear then. One thing is certain: the 100ED is a wonderful lunar telescope. Things never looked so sharp through the C8, nor did the hues include such subtle gradations of grey. I've also never seen Saturn look as good as it did through the 100ED. The Cassini Division neatly divided the rings, and the color was a wonderful, very pale shade of yellow. Glorious. After one night of rooftop observing, I saw something I didn't expect: a brilliant green meteor - or meteorite? - flaming through the sky. Given that we live in Washington, DC - and given the present state of geopolitics - I was momentarily alarmed. But what a sight! Come winter, I wanted to try my hand at something that never really interested me before: multiple star systems. The prospect of seeing a couple stars next to each other never really did it for me, but then few deep space objects are easier to observe from the city. My primary target was Gamma Andromedae, also known as Almach, an apparent double (we now know it's a triple) star system with wonderfully contrasting colors. With Almach riding high in the sky, I had a look one frigid evening. Immediately, I got it: there was something about seeing two incredibly different stars next to each other that's just so beautiful, especially through a refractor. And it sparks the imagination to think about the view from an orbiting planet. Lately, my two-year-old daughter has become ever more interested in astronomy. She loves looking at planets and galaxies in the books I have lying around, she's learned the phases of the Moon, and she's decided on a favorite planet: Jupiter. She's even insisted on having a picture of Jupiter on her bedroom wall! Maybe, in a year or two, we'll have a chance to look through a telescope together. From the time I was a young kid growing up under the dark skies of rural Canada, I dreamed of owning an eight-inch Schmidt-Cassegrain telescope. Glossy advertisements in astronomy magazines promised me that a “C8” would give me the aperture I would need to peer deeply into the cosmos, the portability that would encourage me to peer often, and the robotic gizmos that would unfailingly point me in the right direction. It was an irresistible combination . . . except for the (fittingly) astronomical price. Someday, somehow, I thought, I’d get a good job and save up enough to buy one.

That day arrived late last year, when I found a C8 optical tube assembly (OTA) on sale for a price that seemed hard to beat. And not just any OTA: this was an Edge HD, quite possibly the best mass-produced Schmidt-Cassegrain on the market today. I snapped up the telescope – with a little help from my employer – and waited until I could use it. I waited long, because in cold weather, Schmidt-Cassegrains can take a long time to reach "thermal equilibrium:" the same temperature as the air around them. Until they do, air currents inside their tubes disrupt the view. In the winter, you have to leave your Schmidt-Cassegrain outside for quite a while before using it, and since I currently observe in urban parks that just isn’t possible for me. So I waited for warmer temperatures. Fortunately, they come early in Washington, DC. Tonight, with temperatures in the upper teens, I stepped out with my Edge HD for the first time. Aside from the temperature, conditions were far from ideal. The wind gusted from the southwest, so the “seeing” was far from perfect, and the transparency of the atmosphere also left something to be desired. Wisps of cloud drifted by from time to time, the first signs of a storm system that should be with us tomorrow morning. Yet it was a comfortable night overall, and I looked forward to observing with no risk of frost bite. I set up in my usual observing spot: out behind a police station, in a community garden. Bright street lights are far too close, so I can never develop proper night vision. Yet since I observe in the heart of a little vegetable labyrinth, I'm usually shielded from prying eyes and barking dogs. I have two mount/tripod assemblies that I can use with my C8: the Twilight I setup that I use with my lighter AR 102, and a Nexstar SE computerized mount that came with my (now dearly departed) C6. Both can theoretically handle weights up to around 18 pounds, but in practice neither can quite accommodate the 14-pound Edge HD, with its finder and eyepieces. Still, both are light and small enough for me to walk them the five or so minutes it takes for me to reach my observing sites. This time, I decided to roll out the Twilight I. I wanted to see what I could see with my OTA, and I just didn’t have the patience to deal with occasionally finicky electronics. To minimize the wobbling that usually plagues big telescopes on flimsy mounts, I placed my tripod on Celestron vibration pads. To my surprise, it actually worked fairly well. The telescope shuddered when I moved it and especially when I focused it, but that shudder was not as bad as I’d feared. After unpacking my telescope, I waited around 10 minutes before I lost patience and decided to observe, thermal equilibrium be damned. I snapped in a cheap, 30 mm Plössl eyepiece and wheeled my telescope over to the Orion nebula. The first think I saw when I looked through the telescope was a satellite streaking by. An auspicious start! When it left my view, the Orion Nebula emerged from the inky background. As you might expect, the difference between the Edge HD and my AR 102 was immediately striking. Where the little refractor shows a little arc of misty grey-green light, the bigger Schmidt-Cassegrain reveals delicate tendrils of nebulosity in a giant crescent around the Trapezium Cluster. Next, I reached for in a new purchase. I recently sold my Celestron refractor and used the money to buy a new diagonal and my first quality eyepiece: a 14 mm Explore Scientific 82°. After plugging in the eyepiece and thereby boosting my magnification, I turned to Venus. I was astonished. The AR 102 shows a small, flickering crescent blurred and distorted by chromatic aberration. At 145x, the Edge HD, by contrast, gave a razor-sharp view, even before it reached thermal equilibrium. Since Venus is nearing its closest approach to Earth, when it will be between the Sun and our planet, its crescent is even narrower now than when I last observed it. That made the effect of my sharp, Edge HD optics even more pronounced. There’s no sign of false color with the Schmidt-Cassegrain, so I could fully enjoy the pale, yellow-white atmosphere of Venus. I used a barlow lens to double my magnification to a whopping 290x – the highest I’ve ever used – and somehow the atmosphere (largely) obliged. The crescent flickered in the turbulence but overall remained razor sharp. Although it now filled much of my view, it lost little of its brightness. The view was now truly breathtaking. The atmosphere of Venus looks largely featureless, yet there was an almost magical quality to the zoomed-in crescent. It was amazing to think that this is a world roughly the same size as our own, but with an atmosphere so thick, and so choked with greenhouse gases, that a car would crumple and then melt on the surface. A hell-world deceiving me with the beauty of that delicate crescent. Mars is near Venus right now in the night sky, but it is actually much farther from Earth. As a result, it is roughly 200 times dimmer than Venus, and less than a tenth of the bigger planet’s apparent size. When I trained the Edge on Mars, I was not surprised to find a tiny, featureless globe. The wind picked up, and as it did the seeing worsened. The little red planet seemed to bob and weave across my view. I marveled at how small the disk looked, even at nearly 300x. Space is big. I kept my magnification high and turned to Rigel, a blue supergiant star some 863 light years from us that shines with the almost unimaginable brightness of some 200,000 (!) Suns. Several million years from now, it will explode in a brilliant supernova and its core will become a black hole. Rigel is actually at the heart of a solar system that contains several smaller stars. At 290x, I spotted one of its companions for the first time: Rigel B, actually another star system that orbits the bigger Rigel – Rigel A – at a distance equivalent to 2,200 times the distance between Earth and the Sun. Rigel B consists of two stars between three and four times the mass of the Sun, and one of these might actually be yet another star system consisting of two stars. It’s hard to imagine looking up from the surface of a planet orbiting Rigel Bb, with so many bright blue suns in the sky. Anyway, the Rigel B system is hard to spot with a telescope of six inches or less, so I was happy to glimpse it this time. I finished by taking another look at the Orion Nebula. I kept my magnification at 290x and screwed in my narrowband filter that, you'll remember, only lets in light that shines at the wavelengths of emission nebulae. Now the view was just overwhelming. My eyes were not fully night adapted, and yet: the detail in the nebula around the zoomed-in Trapezium Cluster was just incredible. Boiling grey-green mist. A few closing thoughts. First: this telescope hugely outperforms my AR 102. I expected as much, of course, and the comparison really isn’t fair given the very different roles (and costs!) of both telescopes. Yet I was surprised not so much by how much brighter objects appear through the Edge, but how much sharper they look. Second, the Twilight I mount can hold my C8 in a pinch. The view did wobble at high magnifications, especially during gusts of wind, but this is not a bad grab-and-go setup. It’s pretty amazing that such a powerful telescope can be so portable. Third: I’m beginning to grasp the appeal of “splitting” or “resolving” binary star systems. That’s good, because binaries are some of the few deep space objects that are easy to observe from urban locations. Finally: it sure feels great to have a really high quality eight-inch Schmidt-Cassegrain. I think I’ll keep it. |

Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed