|

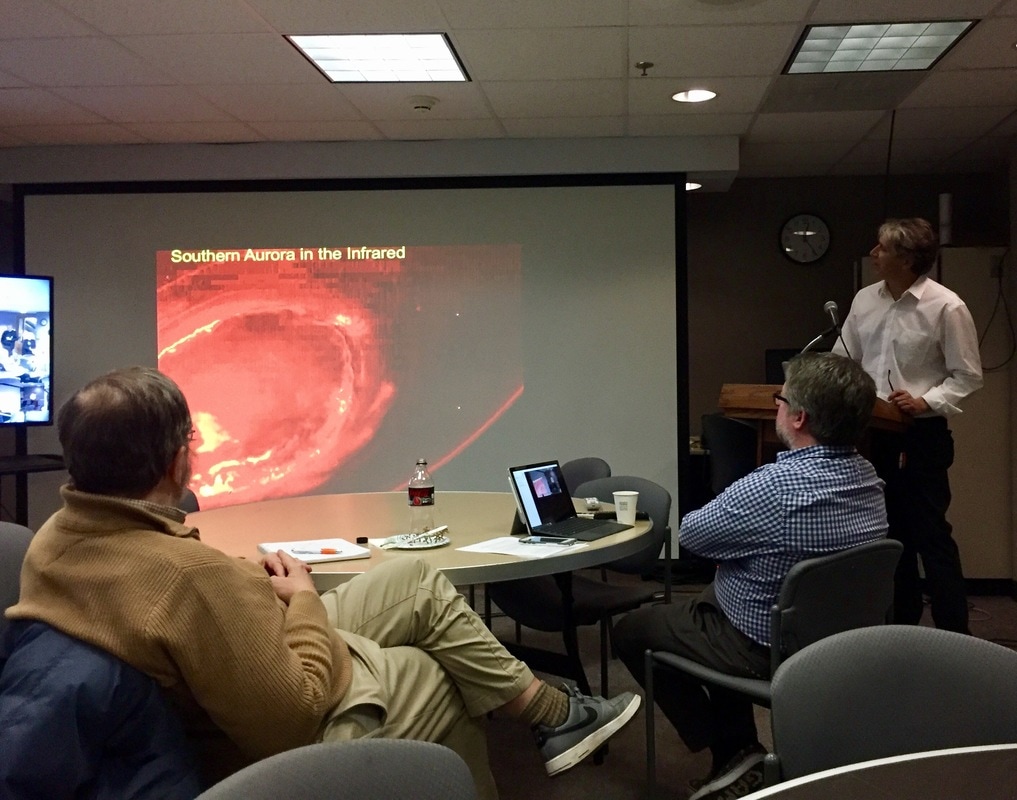

Astronomy equipment! How my wife swoons when I talk about it. Okay, that's a lie . . . but she does roll her eyes. And warns me not to get much more. So of course I have to write about what I've been up to since February, even if I doubt anyone else will read this. Let me start at the beginning. Come February or so I had two achromatic refractors, with designs on sending one to my summer hideout in Winnipeg. After some more thinking, I realized that was impractical. Sending my Celestron XLT across the border would cost more than buying a brand new telescope, and besides: I desperately needed new eyepieces that would do justice to my 8" Edge (hereafter referred to as a C8). I ended up selling the XLT and using my winnings to buy an Explore Scientific 8.8 mm 82° eyepiece and yet another telescope: a C90. The C90 is a neat little Maksutov-Cassegrain that has good optics and is portable enough to take on a plane. The eyepiece is one of the least expensive premium pieces you can get, but it's an awfully big step up over the cheap Plössl designs I'd been using for high magnifications. I also received a Celestron Trailseeker tripod from a friend. In March, I somehow managed to take apart the tripod (not without almost breaking it) and carry both telescope and tripod in a backpack on a flight to Winnipeg. My daughter has been a restless sleeper as of late. In March, it was all but impossible to leave our Washington apartment at night without waking her up. It was a different story in Winnipeg, where we stay in a bigger house. The sky cleared up for our last nights there, which gave me a chance to observe Jupiter for the first time since the summer of last year. Winnipeg is bitterly cold in March, so I left the C90 outside for about an hour to cool down. At last, I wrapped myself in a couple sweaters and a thick coat, and stepped outside. Within seconds, I hit on a depressing realization: the Trailseeker mount and tripod, while light, are awful for observing at moderate to high magnitudes. I weighed them down with a heavy backpack, but still: my view shook and lurched wildly when I tried to make minor adjustments. I had an equally frustrating time trying to use the little finderscope on the C90. It's too small to look through comfortably and too close to the telescope. At least the most important part of my setup - the C90 itself - seems rock solid. In rare moments of wobble-free clarity, my view of Jupiter was among the best I'd had to that point. The north and south equatorial belts were, of course, easily visible, as were the tropical and equatorial zones. I also managed to glimpse a hint of the irreducible complexity of Jupiter's polar regions. And I spotted all four of the Galilean moons, lined up to one side of the planet (if memory serves). When I stepped inside, a thick layer of frost coated my C90. Sadly, the ice revealed that I had smudged the corrector with finger while fumbling with the dust cover, which rattles loose at the slightest provocation. I'll have to clean that in the summer. For now, the C90 seems like a real winner. I'll miss my XLT, but the C90 has almost the same aperture and a longer focal length. It seems at least equally capable on planets. And of course, I can't imagine how I would have traveled with the bigger refractor. Just before viewing Jupiter in March, I attended a workshop at the Smithsonian Museum of Air and Space, where I met Scott Bolton, the Principal Investigator of the Juno mission now orbiting the giant planet. Scott shared some of Juno's latest discoveries, including those incredible images of the planet's poles. Seeing Jupiter after chatting with Scott was a pretty surreal experience. Isn't it crazy to think that people like you and me can lead teams that send machines to distant, alien worlds? After I returned to warmer Washington and my daughter started sleeping a bit better, I took my C8 outside for a second time. I soon realized, to my great disappointment, that my mounts just couldn't handle the bigger telescope. The Twilight I mount that seemed overall adequate when I first used the C8 turned out to be unbearably wobbly when I tried it again. The NexStar mount and tripod that I had ultimately planned to use with the telescope was equally shaky when I ran it through its paces inside. When I bought my C8, I didn't expect that the Edge variant would be heavier than the regular old C8 that the NexStar is designed to handle. And in any case, I usually observe amid some bushes in a labyrinthine garden that's only 40 or so feet away from a sidewalk in an apartment complex. I am, apparently, the stargazing version of Sean Spicer. Did I really want to use a noisy electronic mount with a big red light under such circumstances? And did I want to spend precious time fiddling with electronics when I usually have no more than an hour or so to observe? I decided to bite the bullet and sell both the NexStar setup and the nifty StarSense camera I bought for it. This was, of course, a huge hassle, but after a whole lot of advertising and fretting and negotiating and packing I managed to sell everything for a pretty good price. Now I had to find a tripod and mount that would be light enough to easily carry to my observing site and sturdy enough to handle my C8 with minimal vibrations. I didn't want electronics but I did want something that I could use to easily track planets, which move very quickly across the night sky. I quickly found that my best options for easy planet tracking weighed around 30 pounds, which just isn't practical to carry along with my other gear. The heavier and more awkward this stuff gets, the less I'm inclined to use it. Both the options I initially had in mind were also equatorial setups, which would have taken too much time to set up (at least before I got used to it). After asking the good folks at Cloudy Nights for some advice, I settled on a Universal Astronomics (UA) Macrostar Deluxe mount and a medium tripod. UA is a one person company run by a craftsman who fashions some of the best alt-azimuth mounts and tripods available on the market. The setup I bought from him is actually overkill for my telescope: it should be study enough to handle something much bigger, which will give me the option of upgrading in the (distant) future. Yet the mount and tripod only weigh around 20 pounds combined, which isn't much more than my Twilight I. When it comes to grab-and-go mounts and tripods, I think there's a tipping point somewhere between 20 and 30 pounds. Somehow, 30 pounds just seems unmanageable. Once I bought my new setup - one of the last that will ever be manufactured by UA, it turns out - I also purchased an AstroTech diagonal and a Blue Fireball visual back with the money I had left. An observing instrument is much more than just an optical tube assembly (OTA). Light enters through the OTA, sure, but it then passes through a visual back, bounces off a diagonal, and pours into an eyepiece before it reaches the eye. You can have the best OTA in the world, but you won't experience its full quality without an equally good diagonal and eyepiece. A flimsy tripod and mount has much the same effect, since it's hard to see subtle details when the view is shaking. Anyway, it's taken me about a year, but I think that my main observing instrument finally has no major weaknesses. Nothing is absolutely top of the line, but it's awfully good for my purposes. I've now used my complete setup two times, on warm nights when my C8 reaches thermal equilibrium relatively quickly (though it's never fast). Both times, I concentrated on Jupiter. The UA was rock solid and rolled easily to my target, although I quickly decided that I should have bought the optional handle (it's now on its way). It was hard to sell my fancy electronics, but I now know that I made the right choice. I learned from keeping a huge and increasingly dusty dobsonian in a little apartment that the best gear is the gear you know you'll use. Anyway, on the first night I didn't bother to check Stellarium before walking outside, and I was startled to see volcanic Io nearing the limb of the giant planet. I can't describe how cool it is to see Io as an orange point of light, and to know that the orange comes from volcanic activity. Seriously, how awesome is that? This is a little world nearly 700 million kilometers away, and I can get a sense of its surface. I started at 145x (using my 14 mm eyepiece) and then moved up to 231x with the 8.8 mm. I watched as Io passed into the limb. To my surprise, I couldn't spot a shadow. Was the seeing that bad? Is my eyesight that poor? Well, the seeing wasn't great, but my eyesight is just fine. Perhaps the real issue was and remains my skill as an observer. This may soon painfully obvious, but if there's one thing I've truly come to appreciate as I've gotten back into amateur astronomy over the last two years, it's the skill of being able to see subtle detail on shimmering objects. It takes training, it takes preparation, and perhaps most of all: it takes patience. You need a focused mind and a surprising amount of strength to keep yourself still at awkward angles. Well, I'm improving. On my second night out, Jupiter was a little higher in the sky and the seeing was a bit better (although the sky was less transparent). More importantly, I really tried to concentrate on what I was seeing. I stayed still, blocked the nearby streetlights (with a copy of Sky and Telescope, no less!), and struggled to tease out subtle details when (Earth's) atmosphere settled down and the view stopped shimmering so much. I also tried my first astronomy sketch . . . which is abysmal, as you can see. Still: I spotted some real detail in the equatorial belts, and a hint of festoons in moments of good seeing. I even glimpsed the north and south temperate belts. Maybe I'm getting the hang of this! My C8 really is a joy to handle, but on Jupiter I did wish for just a bit more contrast. The cloud belts don't quite pop like I imagine they would through an apochromatic refractor. The sharpness and brightness of the view is really nice, and you can't argue with the portability of a Schmidt-Cassegrain. It may just be my favorite kind of telescope. But of course: once you see something amazing in this hobby, you start dreaming about the next step. With that said, I think I can take the next few steps simply by becoming a more skilled observer.

That about does it for now. I'm really happy with the changes I've made. I now have a perfectly capable little telescope for my summer stays in Winnipeg, and two great telescopes with very different capabilities and a whole lot of excellent gear in Washington. I'd love to have a better mount and tripod in Winnipeg, but overall I can't complain.

0 Comments

From the time I was a young kid growing up under the dark skies of rural Canada, I dreamed of owning an eight-inch Schmidt-Cassegrain telescope. Glossy advertisements in astronomy magazines promised me that a “C8” would give me the aperture I would need to peer deeply into the cosmos, the portability that would encourage me to peer often, and the robotic gizmos that would unfailingly point me in the right direction. It was an irresistible combination . . . except for the (fittingly) astronomical price. Someday, somehow, I thought, I’d get a good job and save up enough to buy one.

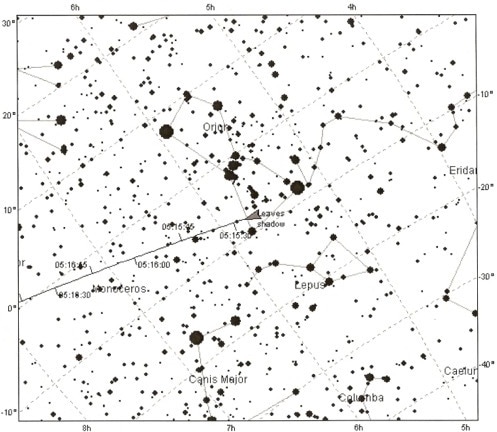

That day arrived late last year, when I found a C8 optical tube assembly (OTA) on sale for a price that seemed hard to beat. And not just any OTA: this was an Edge HD, quite possibly the best mass-produced Schmidt-Cassegrain on the market today. I snapped up the telescope – with a little help from my employer – and waited until I could use it. I waited long, because in cold weather, Schmidt-Cassegrains can take a long time to reach "thermal equilibrium:" the same temperature as the air around them. Until they do, air currents inside their tubes disrupt the view. In the winter, you have to leave your Schmidt-Cassegrain outside for quite a while before using it, and since I currently observe in urban parks that just isn’t possible for me. So I waited for warmer temperatures. Fortunately, they come early in Washington, DC. Tonight, with temperatures in the upper teens, I stepped out with my Edge HD for the first time. Aside from the temperature, conditions were far from ideal. The wind gusted from the southwest, so the “seeing” was far from perfect, and the transparency of the atmosphere also left something to be desired. Wisps of cloud drifted by from time to time, the first signs of a storm system that should be with us tomorrow morning. Yet it was a comfortable night overall, and I looked forward to observing with no risk of frost bite. I set up in my usual observing spot: out behind a police station, in a community garden. Bright street lights are far too close, so I can never develop proper night vision. Yet since I observe in the heart of a little vegetable labyrinth, I'm usually shielded from prying eyes and barking dogs. I have two mount/tripod assemblies that I can use with my C8: the Twilight I setup that I use with my lighter AR 102, and a Nexstar SE computerized mount that came with my (now dearly departed) C6. Both can theoretically handle weights up to around 18 pounds, but in practice neither can quite accommodate the 14-pound Edge HD, with its finder and eyepieces. Still, both are light and small enough for me to walk them the five or so minutes it takes for me to reach my observing sites. This time, I decided to roll out the Twilight I. I wanted to see what I could see with my OTA, and I just didn’t have the patience to deal with occasionally finicky electronics. To minimize the wobbling that usually plagues big telescopes on flimsy mounts, I placed my tripod on Celestron vibration pads. To my surprise, it actually worked fairly well. The telescope shuddered when I moved it and especially when I focused it, but that shudder was not as bad as I’d feared. After unpacking my telescope, I waited around 10 minutes before I lost patience and decided to observe, thermal equilibrium be damned. I snapped in a cheap, 30 mm Plössl eyepiece and wheeled my telescope over to the Orion nebula. The first think I saw when I looked through the telescope was a satellite streaking by. An auspicious start! When it left my view, the Orion Nebula emerged from the inky background. As you might expect, the difference between the Edge HD and my AR 102 was immediately striking. Where the little refractor shows a little arc of misty grey-green light, the bigger Schmidt-Cassegrain reveals delicate tendrils of nebulosity in a giant crescent around the Trapezium Cluster. Next, I reached for in a new purchase. I recently sold my Celestron refractor and used the money to buy a new diagonal and my first quality eyepiece: a 14 mm Explore Scientific 82°. After plugging in the eyepiece and thereby boosting my magnification, I turned to Venus. I was astonished. The AR 102 shows a small, flickering crescent blurred and distorted by chromatic aberration. At 145x, the Edge HD, by contrast, gave a razor-sharp view, even before it reached thermal equilibrium. Since Venus is nearing its closest approach to Earth, when it will be between the Sun and our planet, its crescent is even narrower now than when I last observed it. That made the effect of my sharp, Edge HD optics even more pronounced. There’s no sign of false color with the Schmidt-Cassegrain, so I could fully enjoy the pale, yellow-white atmosphere of Venus. I used a barlow lens to double my magnification to a whopping 290x – the highest I’ve ever used – and somehow the atmosphere (largely) obliged. The crescent flickered in the turbulence but overall remained razor sharp. Although it now filled much of my view, it lost little of its brightness. The view was now truly breathtaking. The atmosphere of Venus looks largely featureless, yet there was an almost magical quality to the zoomed-in crescent. It was amazing to think that this is a world roughly the same size as our own, but with an atmosphere so thick, and so choked with greenhouse gases, that a car would crumple and then melt on the surface. A hell-world deceiving me with the beauty of that delicate crescent. Mars is near Venus right now in the night sky, but it is actually much farther from Earth. As a result, it is roughly 200 times dimmer than Venus, and less than a tenth of the bigger planet’s apparent size. When I trained the Edge on Mars, I was not surprised to find a tiny, featureless globe. The wind picked up, and as it did the seeing worsened. The little red planet seemed to bob and weave across my view. I marveled at how small the disk looked, even at nearly 300x. Space is big. I kept my magnification high and turned to Rigel, a blue supergiant star some 863 light years from us that shines with the almost unimaginable brightness of some 200,000 (!) Suns. Several million years from now, it will explode in a brilliant supernova and its core will become a black hole. Rigel is actually at the heart of a solar system that contains several smaller stars. At 290x, I spotted one of its companions for the first time: Rigel B, actually another star system that orbits the bigger Rigel – Rigel A – at a distance equivalent to 2,200 times the distance between Earth and the Sun. Rigel B consists of two stars between three and four times the mass of the Sun, and one of these might actually be yet another star system consisting of two stars. It’s hard to imagine looking up from the surface of a planet orbiting Rigel Bb, with so many bright blue suns in the sky. Anyway, the Rigel B system is hard to spot with a telescope of six inches or less, so I was happy to glimpse it this time. I finished by taking another look at the Orion Nebula. I kept my magnification at 290x and screwed in my narrowband filter that, you'll remember, only lets in light that shines at the wavelengths of emission nebulae. Now the view was just overwhelming. My eyes were not fully night adapted, and yet: the detail in the nebula around the zoomed-in Trapezium Cluster was just incredible. Boiling grey-green mist. A few closing thoughts. First: this telescope hugely outperforms my AR 102. I expected as much, of course, and the comparison really isn’t fair given the very different roles (and costs!) of both telescopes. Yet I was surprised not so much by how much brighter objects appear through the Edge, but how much sharper they look. Second, the Twilight I mount can hold my C8 in a pinch. The view did wobble at high magnifications, especially during gusts of wind, but this is not a bad grab-and-go setup. It’s pretty amazing that such a powerful telescope can be so portable. Third: I’m beginning to grasp the appeal of “splitting” or “resolving” binary star systems. That’s good, because binaries are some of the few deep space objects that are easy to observe from urban locations. Finally: it sure feels great to have a really high quality eight-inch Schmidt-Cassegrain. I think I’ll keep it. |

Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed