|

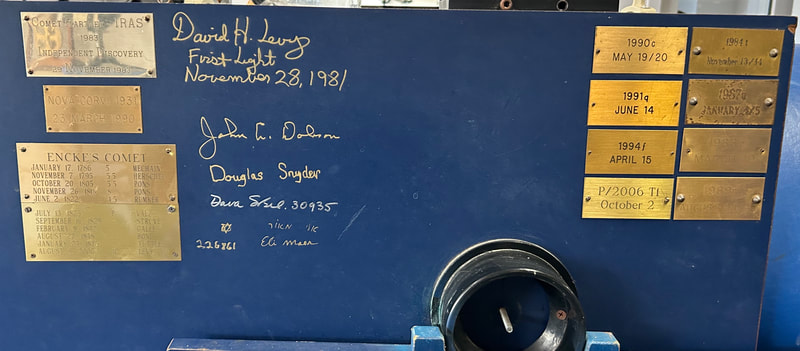

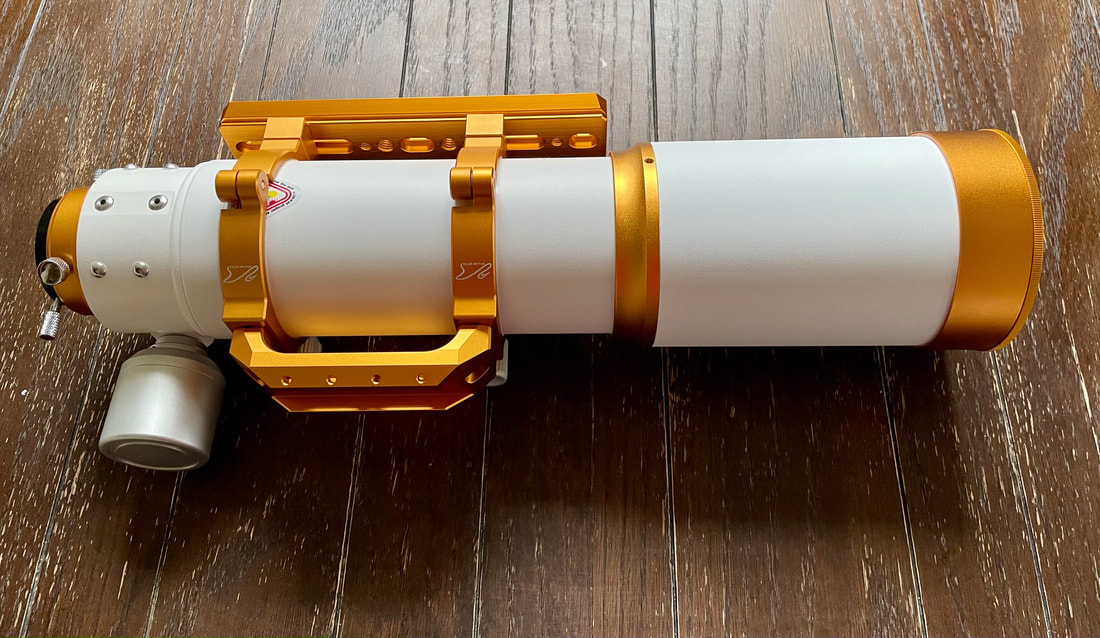

It was midnight on September 1st, and the atmosphere was about as good as it gets for stargazing here in Washington, DC. Transparency was high, seeing was great, Saturn was high in the sky and Jupiter was wheeling over the horizon. My had prepared my TEC 140 in the living room, and prepared to haul it outside. I knew I'd have to walk for a few minutes, and I tried to figure out how best to do it. The telescope itself is just over 20 pounds. The DM-6 mount that holds it well? With its extender, also just north of 20 pounds. The Planet tripod that keeps it all stable? Another 27 pounds. With my eyepieces and including all the cases and bags that house the gear, I was looking at hauling more than 80 pounds. That might have seemed doable were it not for the size everything took up. I simply could imagine no way to drag my gear to my only nearby observing site in fewer than two - possibly three - walks. It had been a long day at work, and I was still tired from recent travels. I left my gear in place. There would be other nights. The next morning, it dawned on me that something was out of whack. Since my little backyard faces north and is usually too shrouded by leaves to be useful for astronomy, I need to be able to easily transport my gear to a more suitable spot. Last year I bought a wagon to make that easier, but dragging it around turned out to be nearly as difficult as carrying my equipment. Given my need to walk to observe, I'd long ago decided that my heaviest telescope would be a medium-sized refractor, and the TEC seemed like the best option available. Somehow, however, I'd ended up with a heap of gear that was almost impossibly heavy to walk with. What happened? Well, it turns out that in amateur astronomy - as in many other things - a sufficient number of little changes can collectively create a new paradigm. The trouble was that the TEC 140 is just a bit heavier and (especially) longer than a medium-sized mount can handle, and that required a big, hulking DM-6. Both DM-6 and TEC 140 are also just a bit too heavy for a medium-sized tripod, especially on a hard surface. Enter the Planet tripod. A medium-sized telescope therefore required gear that was heavy enough to hold something much larger. Yes, it was beautifully stable once set up. But that didn't mean much if it was too massive to move. With a heavy heart, I put my TEC 140 up for sale. Within hours, a friendly local buyer had scooped it up. While I was, on some level, sorry to let it go, it also struck me that I'd made few genuinely special memories with it. I tend to grow attached to instruments that have genuinely shown me something new. My dearly-departed TV 85, for example, revealed just how much sharper a refractor could be in our DC weather than any other kind of telescope - and gave me my first unambiguous view of the Great Red Spot. My Takahashi FC 100DC gave me truly unforgettable views of Mars, and the shadows of Jupiter's moons. My APM 140 gave me even more stunning views of Mars and Jupiter, and then the 100DZ left me breathless while gawking at the Moon. The TEC 140 did give me a wonderful sensational of texture in the Jovian clouds. But that wasn't quite enough to build a bond. After I sold my now-useless DM-6 and Planet tripod, I had some decisions to make. Should I downsize by, for example, buying a jewel-like Questar 3.5? I opted it against it after reading convinced me that the iconic little telescope could simply not compete with the also-portable 100DZ. I opted to attempt to buy two lighter but still medium-sized telescopes that I hoped could largely replace - or even improve upon - the capabilities of the TEC, while requiring a much lighter tripod and mount. The first of those telescopes: a TSA 120. Takahashi's four-inch refractors have long been my favorite telescopes. I decided to try something a little bigger in the five-inch TSA 120, an air-spaced triplet (a refractor with three lenses) that, I thought, could gather meaningfully more light than the 100 DZ. I'd long resisted buying an air-spaced triplet, since these telescopes weigh more than doublets and take much longer to cool down. The weight of the TSA 120, however, splits the difference between the TEC 140 and 100 DZ, and I figured I could simply let it acclimate in my backyard before carrying it to a more suitable observing site. To my delight, I managed to buy the TSA 120 on sale. When it arrived, I was immediately surprised by its compact size. Although its aperture is just a bit lower than that of the TEC 140, its dimensions seem closer to those of the 100DZ than the TEC 140. I also had not expected it to ship with a quality two-speed focuser. You can purchase the telescope with the bulkier but ostensibly more precise Feathertouch focuser, but Takahashi's equivalent is, to my mind, just about as good. Truth be told, I don't really understand the obsession with replacing the focusers on premium telescopes, like the Takahashi refractors. All you need is something that gets the telescope in focus, and to my mind the stock focusers do that very well. It's a small point and one I've brought up before, but still: I can't get enough of the Takahashi aesthetic. The white tube, black trim look is classic for a reason, but here's to doing something a little different. I think Ed Ting once mentioned that Takahashi telescopes have an indefinable Zen character to them, and that feels about right. It makes me inexplicably happy to see them. That's not to say that the build quality of the TSA 120 exceeds that of the TEC 140, but I do prefer that cream-colored paint with mint-green accents. Anyway, on September 14th the sky cleared and temperatures cooled just after I'd finished setting up my new TSA 120 (with Moonlite tube rings courtesy of a very helpful veteran of the Cloudy Nights forum). By then, I'd found that my Berlebach Uni tripod and (wonderful) NoH's Mount CT-20 easily support the TSA 120, which made for a setup that weighs about 40 pounds total - half as much as the TEC 140 and its equipment! I bought a Stellarvue C9S case for the TSA 120 that fits it exceptionally well, and I left the telescope outside, in its case, for about 40 minutes before using it. This time I easily walked to my nearest observing site, in the courtyard of my building. Saturn is just about a month past opposition, and high above the horizon at about 11:00 PM. I decided that its light would be the first that entered my new telescope. I have a strange relationship with Saturn. To me, it's still the most impressive object in the night sky. Yet as a target for repeat observation, it pales in comparison to Jupiter and Mars. Its rings change their tilt over time, sure, but I can rarely make out enough detail on its disk to give me the impression that I'm viewing an evolving world. Well, the TSA 120 might change that. At about 90x with my Delos 10mm eyepiece, Saturn was spectacularly well defined. I'm not sure I've ever seen such fine detail in the grey clouds above its rings. The outline of its rings was razor-sharp, the Cassini division clearly outlined. It was, I decided, about the best view I've had of the planet. Mosquitoes started to emerge, whining near my ears, but I was so distracted that I soon found myself covered in bites. I packed up and walked back home - easily. When I got inside, I was a little taken aback. I wasn't sure exactly how my view of Saturn compared to the best I had with the TEC 140; almost exactly two years ago I marveled in these pages that the bigger refractor gave me an "absolutely stunning" look at that planet. And yet, I couldn't say while unpacking the TSA 120 that I'd ever had a better view of Saturn. The sharpness is what most impressed, and the collection of bright little moons, swarming around the planet like moths around a lantern. Granted, both seeing and transparency had seemed better than average. But if the TSA 120 gave me a view that left me so satisfied, why had I hauled around so much more weight for so long? On September 15th, the pellucid evening sky invited another round with Saturn. This time, I brought out the second telescope I'd purchased: a Mewlon 210. These unusual Dall-Kirkham telescopes are a little like condensed Newtonian reflectors, with very long focal lengths. They cool down more quickly than other catadioptric telescopes - like the ubiquitous Schmidt–Cassegrain - and have none of the dew problems that can hamper these telescopes in a humid environment (Washington, DC certainly qualifies). Takahashi makes its Mewlon variants to exacting specifications, and that should in theory make them exceptional planetary telescopes. They are famously tricky to collimate, however, and they must be perfectly collimated to realize their potential. They also take a lot longer to cool down than (smaller) refractors, and their field of view is much narrower. They are much more sensitive to poor or mediocre seeing than those refractors, and the vanes that hold their little secondary mirrors produce faint rays around bright objects. The Mewlon is, therefore, a specialist instrument. Yet when conditions are right, all Mewlon variants are designed to give spectacular views of the Moon, planets, and double stars: precisely those objects I most enjoy observing in the city. At over eight inches in aperture, in good seeing the Mewlon 210 should in fact reveal those objects with even greater brightness and detail than the TEC 140. And - remarkably - it weighs much less than that telescope, despite looking much heavier. On that note, I will add that, in my view, the Mewlon 210 is quite possibly the most impressive amateur telescope to look at. It is simply beautiful. It looks like a jet engine crafted with care by a Swiss clockmaker. What's more, it comes complete with a finder scope that stays perfectly aligned with the telescope, and is so robust that you can use it as a handle. You may have to collimate the telescope from time to time, but you never have to align the finder - and that makes up for a lot. So how did the Mewlon perform on Saturn? Sadly: not as good as the TSA 120. It was clear from the box that the telescope had been handled roughly on its way to me, and something - or someone - had knocked it out of collimation. All the same, it was only a little off, and I hope I can tweak it to perfection sometime soon. Maybe in my backyard, after the leaves finally fall? Remarkably, atmospheric seeing and transparency were again above average last night, so I stepped out again with my TSA 120. This time, I waited until about midnight, when Jupiter had climbed above the horizon. I turned to Saturn first, and now the view was truly breathtaking: slightly but meaningfully more vivid - more crisp - than I'd seen even a couple nights earlier. I quickly switched to a 4.5mm Delos, giving me a magnification of exactly 200x. In my experience, Washington's sky rarely allows that kind of power. Yet to my astonishment, the atmosphere repeatedly settled down to allow a remarkably sharp view at that magnification. The subtle mingling of grey, beige, and buttermilk threads in the planet's atmosphere was simply a joy to tease out, and I could make out glimpses of structure in its ring system that I'm not sure I've ever seen before. Was this my best-ever view of Saturn? I concluded that it probably was, and again I was so enthralled that I lost track of the mosquitoes biting me. Eventually I wheeled the telescope around to Jupiter, and now the view was a little softer. The planet was still climbing out of (Earth's) thicker atmosphere near the horizon, and seeing seemed less stable in its corner of the sky. Still, I routinely made out wonderfully delicate detail in its many belts and zones. It's a little silly to compare the view through different telescopes on different nights, and perhaps sillier still to compare exceptional refractors to one another. Yet even (or perhaps especially) the most unscientific comparisons are fun, and in this case I think they're instructive. On my nights of observing, I judged that the TSA 120 showed just a bit less contrast - on Jupiter especially - than the TEC 140, and perhaps the APM 140 I once had. Yet it showed more contrast than the 100DZ - the planets seemed just a bit more vibrant - and the views were just as sharp; sharper than anything I could remember seeing through the bigger refractors. I was particularly impressed by how easily the TSA 120 snapped into focus, and how readily it gobbled up magnification. On both fronts, it seemed to exceed the performance of any telescope I've tried using. Now, all the usual caveats about the atmosphere certainly apply, but that's the point. When telescopes get to a certain quality and size, it's often factors beyond the performance of their optics that are most important. I truly did love my TEC 140. Yet I can't conclude that it's superior to the TSA 120. Both telescopes have brilliant optics that, in Washington DC, are almost invariably limited by the atmosphere, rather than their innate capabilities. Yet a setup that supports one telescope is fully twice as heavy as the other. When you're tired at the end of a long day, it doesn't take much to discourage even a quick observing session. With that in mind, the lighter, more portable setup is more often the best one. At least, it seems like it is for me. I know this is a long entry, but I can't conclude without mentioning a recent trip to the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada archive in Toronto. Since I was last there, the society's staff have set up several dozen telescopes that had me feeling like a kid in a candy store. There were two beautiful Unitron refractors, an exceptionally long Antares achromatic, a huge Cave reflector . . . the list goes on. But one in particular stood out - the ugliest one, by a long shot. Yes, that's David Levy's trusty telescope: a makeshift Dobsonian reflector complete with duct tape and what looks like a jar (!) over a finder scope. Plaques commemorating discovered comets line its base like kills on a Spitfire. Here was a poignant reminder that the best telescope - or indeed the best machine of any sort - is the one that works for you, and you alone.

2 Comments

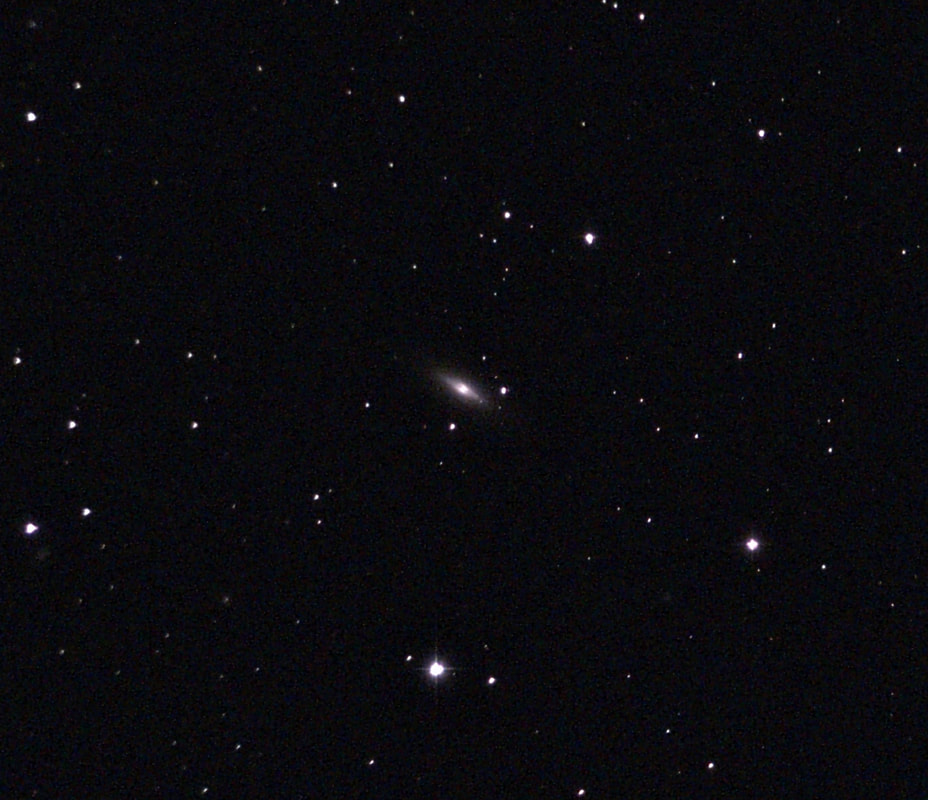

Recently, I've been on a mission to optimize my grab-and-go setup. Slowly but surely, parks that offered dark corners for a telescope have been saturated with bright lights: the kind that needlessly waste energy, confuse nocturnal animals, and pollute the night sky. I have to walk further than I have before, or settle for less than ideal observing conditions. To that end, setups that used to feel perfectly mobile now are discouragingly cumbersome to use. I admit I was tempted to swap my FC-100DZ for a lighter telescope, such as the FC-100DC I used to have and love. Then I had an epiphany - one I should have had long ago. With its diagonal removed and dew shield retracted, the DZ is just over two feet long. Couldn't I find a padded bag that long? If so, the DZ would be as easy to transport as my dearly departed TV 85, while offering considerably better performance. I found the bag - for just $23! - and wow: what a difference. It's strange but true: the DZ is as transportable as much smaller telescopes, but offers truly stunning views of everything that shines through light-polluted skies. The other night, I pointed it at Saturn, which is just now reaching opposition (its closest annual approach to Earth). The view was spellbinding, with glimpses of detail in the planet's clouds that were among the finest I've seen. On the other hand, DC's summer mosquitoes did not give me a moment's rest, and I was grateful that my little setup takes just a few minutes to disassemble. Then, last weekend, it was off for what has become an annual trip to the beach near Lewes, Delaware. I brought my EVScope 2, eagerly anticipating darker skies. Unfortunately, I soon found that atmospheric transparency was lower near the beach than it has been in years past - owing, once again, to that wildfire smoke. Worse, my recent experience with a truly pristine sky in Manitoba left me unimpressed with the view in Delaware. Sure, the Milky Way was barely, and I mean just barely, visible after fifteen minutes outside in the dark. But there was simply no comparison. I occasionally fantasize about selling my EVScope in exchange for a more capable astrophotography setup. The three (!) clear nights I experienced in Lewes reminded me why I have that fantasy - and why I haven't acted on it yet. First, the telescope needed collimation. If you've read any reviews of the EVScope, you'll know that some complain about the need to collimate such an expensive gizmo. Let me assure you that it's much easier than collimating an SCT, for example. Even when the telescope is badly misaligned - as it was for me in Lewes - the entire process takes a few minutes at most. The real problem is that Unistellar's instructions include a glaring error. To collimate the telescope, it should not be pointed at a particularly bright star - I tried Antares - because the star's brilliance will not allow you to see the secondary mirror when out of focus. I suppose it's a minor detail, but this little mistake can create a lot of frustration. Usually, it takes just moments to align the EVScope and get it ready to slew to any object you can imagine. Usually. On one night in Lewes, I had to turn off the telescope a couple times before it aligned itself. On two other nights, it did not precisely center objects after finding them - so that, at the telescope's highest magnifications, objects were simply offscreen. On a third night, everything worked seamlessly. I carefully leveled the telescope, collimated it, and waited over thirty minutes for it to acclimate. That may not sound arduous to veteran amateur astronomers - but it's hardly ideal for a grab-and-go setup. When the telescope is aligned, it tracks objects seamlessly. The trouble is that its altazimuth mount cannot perfectly track stars on long exposures. This isn't visible while peering into the eyepiece, but it does show up clearly in astrophotographs taken with the telescope. Since most people will use the telescope by staring at their phones or tablets - in fact, some Unistellar models don't even have eyepieces - this is a serious limitation. Even this six-minute exposure of the Eagle Nebula has distorted stars. Stars are also distorted - even through the eyepiece - because stars shimmer in all but the steadiest atmospheric conditions. When using a traditional telescope - especially a refractor - you may see a roving, flickering pinpoint. Yet the EVScope takes exposures to provide its bright views of deep space objects, and in these exposures the undulating pinpoints that are stars in mediocre seeing all congeal into blurry blobs. For a refractor aficionado like myself, the effect is deeply unsatisfying. To me, it really does not feel like you are actually peering into space when you use an EVScope. Occasionally I wonder: what am I getting here that I could not obtain by finding images on the internet? Have a look at this shot of the Wild Duck Cluster, for example. The problem is compounded by the reality that Unistellar's software cannot quite compensate for the effects of light pollution. Overall, it does a remarkable job - I'm still amazed that I can admire the Triangulum Galaxy from downtown DC, for example - but there's still a good deal of noise even under a Bortle 4 or 4.5 sky (as in Lewes). Have a look at this 24-minute exposure of the Pinwheel Galaxy, and notice the noise. Another inconvenient truth is that, even with the galactic core above the horizon in the summer, there just aren't that many objects that truly impress when viewed with the EVScope. You have to remember that although the EVScope allows you to view galaxies and nebulae that are far beyond the reach of a comparably-sized traditional telescope, it is also incapable of providing satisfactory views of many objects that such a telescope would reveal. Open clusters, double stars, the Moon, and the planets: everything that impresses when seen through a telescope like the Takahashi FC-100DZ is underwhelming at best when viewed with the EVScope. In practice, dozens of objects in the EVScope's catalogue look like this, and hundreds are far less impressive. The EVScope also seems to have a weak wifi signal. Walk twenty feet away, and you're likely to lose it. You can forget about sitting indoors while operating the telescope. That's too bad, because mosquitoes really can make it hard to stay outside in our muggy summers. In other places, winters are just too cold for comfortable observing. Wouldn't it be easy for Unistellar to include some way of amplifying the wifi signal on its $5,000 device? So yes, I was getting a little annoyed in Lewes. I kept imagining what my TEC 140 might reveal; not nebulae in a distant galaxy, sure, but pinpoint stars on a velvety black background, and spectacular planetary views. This is the best that the EVScope can do on Jupiter, even after a recent software update that dramatically improves planetary performance. I admit: I could go on. Suffice it to say that my nights in Lewes reminded me that, if you buy an EVScope, you really should go for the EVScope 2. This is because the eyepiece is really a lot better than some reviews suggest. Somehow, images of nebulae and galaxies are much brighter and sharper through the eyepiece than they appear to be when viewed on a phone or tablet. The distortions I complained about above - those blurred stars, in particular - are also minimized when viewed through the eyepiece, likely because the small scale of the image mitigates them. As a result, I am consistently impressed by the nebulae and galaxies I see through the eyepiece; so impressed that I take an image that then disappoints. Just before I took the image of the Pinwheel Galaxy that you've already seen, I invited my wife and our friend outside to have a look. Both are astronomy novices, to put it mildly. Both seemed skeptical that they'd see much. Yet when both craned over the EVScope eyepiece, they gasped. They could not believe that they had seen a whole galaxy across 20 million years in time and space. They kept saying how cool it was. "It's almost like one of those picture slide viewers," my friend eventually said. Indeed. You see so much more - and so much less - than you would with an ordinary telescope. That is why I think I'll keep the EVScope . . . for now. Here are some extra images, showing medium-length exposures of some of the best-known sights in the summer sky. To put it mildly, it's been a dreadful summer for astronomy in Washington, DC. The primary culprit is wildfire smoke, which seems to waft into the city with every clear night. As a professor whose primary preoccupation is climate change - and as a dad - the smoke fills me with dread. It is alarming for any number of reasons, but it has extra significance for those enamored with the night sky. The atmosphere is likely to be less transparent on a warming planet, owing either to wildfire smoke or aerosols intentionally seeded into the stratosphere. That second possibility is known as solar geoengineering. It's cheap (compared to the cost of global warming), it's likely to be effective (despite a litany of troubling side effects), and I'm increasingly convinced it will happen within twenty years. In fact, this summer the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy released a primer that more or less accurately describes where the science of geoengineering currently stands. If plans currently on the drawing board someday take off, astronomy as a science and hobby will change - quite possibly for the rest of our lives. In all likelihood, planetary observation won't change much, and Electronically-Assisted Astronomy will still reveal deep space marvels. Yet my suspicion is that traditional telescopes - including big Dobsonian reflectors - will be far less effective for observations of diffuse objects far from our Solar System, such as nebulae or galaxies. You've been warned! Anyway, I did manage to see one spectacular sight in DC this summer. In May - just before the worst of the smoke surged south - a supernova exploded in the Pinwheel Galaxy. I hauled my EVScope to a nearby field and had a look. The above picture is all I managed to capture, but the view through the eyepiece was far more impressive. I still can't believe I managed to see an exploding star - and, in all likelihood, the formation of a black hole - 21 million light years from Earth. More recently, I travelled with my family to Winnipeg. Despite its closer proximity to the many wildfires burning through British Columbia, the city has been less affected by wildfire smoke than Washington, DC. The sky is not quite free of smoke, but it's a good deal more transparent than it's been further south. This was my first trip to the city since the pandemic, and I'd nearly forgotten that I cobbled together a fairly impressive little observing setup here. Four years ago, I had a Twilight I mount delivered to my in-laws. I also purchased a C6 shortly after I was last here, and it was still in the box when I arrived this time. I unpacked it with some trepidation - the last C6 I purchased was damaged upon arrival - but not to worry: to my relief, the little telescope was in perfect condition. With everything assembled, I was struck by how well the C6 fits on the Twilight mount. I don't think it could handle a C8, but a C6 is just about perfect. It's quite stable, convenient to look through, and remarkably easy to move. In fact, I can lift mount, tripod, telescope, diagonal, and eyepiece - everything - above my head with ease. I swapped out the standard Celestron diagonal - a child's toy - with a TeleVue Everbrite, and used a Baader Mark IV Zoom for an eyepiece. The field of view, I must admit, is a little too narrow, but then a Schmidt–Cassegrain really isn't a wide-field instrument. I was gifted one clear night after another since arriving here, and used the first two nights to admire the Moon. This far north, it doesn't rise far above the horizon right now, and it is tinted a beautiful pinkish-gold by the diffuse smoke in the upper atmosphere. Seeing was mediocre at best, but the telescope turned out to be well collimated, and the view was quite striking. As the above image attests, the Moon was not as sharp as it would be through one of my refractors. Even in mediocre atmospheric conditions that prevailed here, the Takahashi, I'm sure, could have shown me more. But when you consider the relatively low cost of a C6 - albeit much higher than it was pre-pandemic - the telescope is a remarkable performer. I was particularly impressed by how cleanly it snapped into focus; in fact, finding focus seemed a little easier with the C6 than it is with my refractors. I was genuinely delighted to discover that Saturn now rises high enough above the horizon to observe at around midnight. The planets might have drawn me outdoors this summer despite the wildfire smoke, but often they had set before I could step outside. Well - Saturn, at least, is back.

The C6 offered a really satisfying view of the planet, with the Cassini Division clearly visible at 75x. I'm not sure my Takahashi would have done that much better, given the seeing. In a cooperative atmosphere, I have no doubt that the refractor would outpace the Schmidt–Cassegrain; there is a delightful crispness to its views that the stubbier telescope can't quite match. And of course, it never needs to collimate or acclimate (for long). Nevertheless, I was stunned when, later, the C6 showed me Arcturus as a perfect orange point: something I had not expected from a Schmidt–Cassegrain. For those less obsessed than I am with getting the absolute best views that a (modest) aperture can provide, I suspect it would be impossible to justify the extra cost of a 4" apochromatic refractor over a C6. Well done, Celestron! Anyway, I had a truly wonderful half hour on the porch, the crickets chirping nearby as I admired the ethereal beauty of Saturn's rings. I was struck by how much their tilt relative to us has changed over the past year, and I fear that they will - briefly - disappear from view entirely in the months to come. It will be fleeting. Soon enough, the rings will return, and the planet will regain its grandeur. For me, one of the joys of astronomy lies in the knowledge that however badly we muck up our planet, countless wonders glitter beyond our reach. With or without us, it's a beautiful universe. Binoculars have long frustrated me. While I've thrilled at catching glimpses of rocket launches or lunar craters with big Celestron binoculars here in Washington, DC, I could never hold them steady enough to make out more than blurry glimpses. I opted for more manageable binoculars, but still: no matter what I did, the view was always disappointing. Eventually I gave up and decided that binoculars were just not for me. Then I learned about image stabilized binoculars: remarkable little devices that use gyroscopes and moveable lenses to cancel the inevitable vibrations caused by human hands. The high cost and relatively small size of these binoculars at first convinced me that it just wouldn't be worth it to buy one. Eventually, however, I found that I'd accumulated a heap of eyepieces I no longer used, and after selling them I took the plunge. I bought a pair of Canon 12x36 Image Stabilization III binoculars. When they arrived, I decided to try them out on the abundant birds in my backyard. I'm not a bird watcher - the one time I went on a bird watching tour at a conference, I was nearly abandoned in the middle of a desert - but I have to say, I was absolutely floored by the view. It really felt like the bird I was looking at - a female cardinal high up in the canopy - was right there in front of me on the table. The view was absolutely crisp, razor-sharp with no false color, and better yet: it was stable. It's hard to emphasize enough what a difference that makes. I was eager to see what I could make out on the planets, which had become very prominent in the mornings. When I tried, however, I was disappointed. This time I noticed some false color, and the image wasn't quite sharp enough for me. I figured, sadly, that even the best binoculars might not have much value for me in astronomy. Yet last night I couldn't resist the temptation to try out the binoculars one more time. The last "supermoon" of the year was rising, the Perseid meteor shower was peaking, and I really wanted to go to my favorite park. It's a long and painful hike with a telescope, but easy and fun while riding a scooter with one-pound binoculars in a backpack. I zipped out at around 11 PM, and made it to the park in no time.

The very first thing I saw as I reached my preferred observing spot was a bright meteor: an auspicious start if ever there was one. When I looked at the huge, golden Moon, however, I was again disappointed: it was just a bit blurry, with too much false color. This time I carefully adjusted the binocular's collimation and focus, waited a few minutes for it to acclimate, and tried again. What a difference! Now the Moon was wonderfully sharp - like those birds in my backyard - and to my astonishment the view really wasn't much less impressive than it is with my Takahashi refractor at low magnifications. The amount of detail I could make out was nothing short of miraculous. Then I turned to Saturn, and could hardly believe it when I easily made out its rings. Jupiter was rising above the horizon, and sure enough: there were its moons, perfectly clear in binoculars with an aperture of just 36mm. There was something exhilarating about how easy it all was. The binoculars are little bigger than my hand, and of course they required essentially no setup. But there I was, with bats fluttering overhead (I saw one through the binoculars), admiring the heavens. After about 15 minutes, I had that giddy feeling I sometimes get during my best nights under the stars - and since I wanted to leave on a high note, I hopped back on my scooter and sped home. Image-stabilized binoculars cost a lot more than a decent pair of regular binoculars (but a lot less than premium binoculars with high-quality optics). However, I'm now convinced that it's difficult to compare them to their lower-tech cousins. It's a completely different experience to use them. Because their views are stable, looking through them is more like using a telescope than regular binoculars - with the added benefit of the three-dimensional experience that binoculars (or binoviewers) uniquely provide. I have a real weakness for little instruments that provide outsized views (it's why I loved my TV 85 as much as I did). After last night, I have to conclude that the diminutive Canon 12x36 is, quite possibly, the most impressive optical instrument I've ever tried out. It doesn't often work out this way in amateur astronomy, but sometimes big things really do come in little packages. The planets are all lined up in the early morning sky, and the summer atmosphere here in DC can really settle down at night. The Sun begins to rise at around 5 AM, however, so getting up early enough to see the planets means sacrificing sleep. Still, I couldn't resist setting out twice, over the past few weeks, to catch glimpse of Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. First, on June 25th, I marched over to a nearby soccer field with my Takahashi in hand. Seeing with supposed to be better than average, while transparency was a little worse. When I set up, however, I realized that the atmosphere was actually surprisingly turbulent around the eastern horizon. That kept me from getting a good view of either Jupiter or Mars, which was quite disappointing given how tired I was. When I swung the refractor over to Saturn, however, I realized that the atmosphere was better towards the south. I had a really nice, crisp view of the planet and its rings before wisps of high-altitude cloud convinced me to pack up. A few days later, I celebrated my daughter's sixth birthday. While hauling stuff to her party, I realized that a little wagon would really help. It also dawned on me that a big enough wagon could carry my TEC 140, together with its tripod, mount, and eyepieces. I pulled the trigger and bought a UIDYGGD Folding Wagon, hoping that I could use it to haul my biggest telescope to a nearby field. In summer the leaves are just too thick, and the streetlights are just too bright, to use the TEC 140 in or near my backyard.

On the early morning of July 11th, I loaded everything into the wagon and began to wheel it towards the field. After about thirty seconds of hauling, I nearly gave up. I was dragging everything uphill, and my back was on fire. I paused, then persisted - and after fifteen minutes, reached the field. It occurred to me that there was no way I could have made it there while holding my telescope case in one hand, and pulling my rolling suitcase - which stores my tripod, mount, and eyepieces - in the other. After I set up, I turned to Mars and was rewarded with easily my best view of the planet this year. Not only was the south polar cap clearly visible, but so was a latticework of dark albedo features spidering up towards the planet's equator. Turning, to Jupiter, I was delighted to see the shadow of a Galilean moon, just beginning to emerge onto the planet's western limb. This time seeing really was better then average. It seemed there were more cloud belts than I could easily count, and there was that sensation of infinitely intricate detail that the clouds can have when Earth's atmosphere is sufficiently stable. Saturn, however, again stole the show. I've never had a view of Saturn using the TEC 140 that was quite as good as those I've enjoyed of Mars or Jupiter. But this time, with Saturn fairly high in the sky, I was treated to perhaps the sharpest view I've ever had of the planet. Not only was the Cassini Division plainly visible for the entire length of the rings, but I could make out multiple rings - which is rare for me -and the shadow of the rings on the planet was a perfect, velvet black. I also made out a whole slew of moons, and beautifully detailed, turbulent clouds on the planet's creamy yellow-white disk. It was a view that fully justified my lack of sleep - in fact, one of the best views I've ever had of a planet. I usually prefer viewing Jupiter and Mars to Saturn, because the appearance of the closer planets changes much more than that of Saturn. But when the atmosphere cooperates, the night sky offers nothing more beautiful - or more hauntingly alien - than Saturn and its rings. We've had a few clear nights this week, with seeing and transparency both hovering near average. It's been a demanding month at work, but I had to step out last night, Takahashi in hand, to catch a glimpse of Jupiter and Saturn. The glare of the rising full Moon, however, discouraged me from going to the park near my house - it would just be too bright, I thought - so I popped up to my rooftop for a quick look. That rooftop really isn't suited for serious observing. Somehow the concrete slabs thrum with vibrations from my building, and the warm air boiling from the rooftop always worsens the seeing, sometimes dramatically. Nevertheless I did steal a few clear, stable glimpses of Jupiter and Saturn: enough to make out countless zones and bands on Jupiter, and the Cassini Division on Saturn. The small, orange disk of volcanic Io, I believe, was just about to move across the Jovian clouds; I've been so overworked lately that I didn't bother to check.

Then I looked over at the Moon, still rising in the east. Like most observers, I always prefer the Moon when it's only partly illuminated - I love the shadows along craters and mountains - and in any case tonight it was clear that the atmosphere along the eastern horizon was just not going to cooperate. Seeing and transparency in that corner of the sky, it seemed, were particularly challenging. Still, the Moon is always - always - a striking sight through a fine refractor, no matter the state of the atmosphere. After about fifteen minutes, I packed up and stepped back inside, thoroughly pleased that I'd ventured out despite my fatigue. It's almost always like that: even when tired, there are few things I'd rather do. Conditions were glorious last night - temperatures in teens, seeing and transparency both above average - and I was feeling surprisingly energetic, so I dragged my TEC 140, DM-6, and Berlebach Uni tripod out the door, and walked 15 minutes to my favorite nearby park. I had about 80 pounds of gear with me, but somehow, last night, I found it quite manageable. It was heartening to know that I could transport the TEC 140 without much more difficulty than I used to haul about my dearly departed APM 140.

When I set up shop I noticed that the sky was strikingly dark, and that the stars and planets scarcely twinkled. I immediately plugged in my highest-power Delos eyepiece - which manages 217x - and targeted Jupiter. What a view! I lost track of how many cloud belts I could make out, and subtle detail was everywhere. I was looking at the same hemisphere I had admired about a week ago with the TEC 140, and that same barge I noticed then was still around. Now the Galilean moons looked even more clearly like disks, and therefore like real little worlds. I decided that the difference between the TEC 140 and the APM 140 lies in the sensation of texture on the planets. More than the APM, the TEC gives me the feeling that the clouds of Jupiter, for example, have depth, which in turns makes it clearer that I'm observing a three-dimensional object. That really makes a profound difference. Both the APM and the TEC provide views that are far better than those of four-inch refractors, including the Takahashi FC-100DZ. There's just so much more contrast visible with the bigger refractors, and on a low-contrast object like Jupiter that means everything. The view of Saturn was a bit less perfect, just like it was a week ago. While I could easily crank up my magnification past 200x on Jupiter - which is usually about the limit in the Washington, DC air - Saturn benefitted from lower magnification. Still, I was struck by the obvious complexity of its ring system in moments of good seeing. It seemed I could clearly make out not only the Cassini division, but at times I got a flicker of brightness variations, attesting to distinct ring groupings of varying brightness. After observing Jupiter and Saturn for a while, I wheeled the telescope east to observe the Pleiades at low magnification, which was pleasant but not noticeably different than it is in a smaller refractor. Then I realized that Uranus had climbed well over the horizon, and in fact that it should now be near 37 Ari, a star of very comparable magnitude (5.75 to 6 for Uranus). I've never observed Uranus before. I've tried to find it, but come up empty time and time again. It's actually a little embarrassing; it shouldn't be that hard to identify. So, this time, with the weather perfect and armed with a powerhouse telescope, I decided to give it a try. The trick was to find Menkar (Alpha Ceti) and Kaffaljidhma (Gamma Ceti) in the constellation Cetus. While these are bright stars - Menkar in particular, at magnitude 2.5 - it's telling that even with atmospheric transparency better than average, I could only barely make them out. DC's light pollution is especially bad to the southeast from my position, which is where the national mall and the rest of the city's downtown area is located. Anyway, once I found those two stars I used them to triangulate Mu Ceti, which at magnitude 4.25 truly was at the edge of my perception. These three stars in Cetus formed a narrow triangle that pointed to Uranus and 37 Ari. In fact, the length of the triangle was actually greater than the distance of the planet from that triangle. Using my finderscope, I searched. And searched. About 20 minutes went by, and no dice: I could see only stars. I started scanning more broadly, thinking I'd done something wrong. Then I checked my star map - which I get through an app called Stellarium - and suddenly it hit me: I'd been looking for something that looked like a planet. But Uranus is so far away - and therefore so dim - that it should really be indistinguishable from a star at low magnifications. My problem was that I had plugged in my 24mm Panoptic eyepiece, which gave me a magnification of just about 40x. I needed to trust my map and really crank up the power on the star that, I knew, must be Uranus. So I did. With the high power Delos eyepiece back in and my magnification at 217x, suddenly the planet became obvious: a little grey-green ball, wandering through space. I could make out, at most, only the subtlest detail on that little ball - and really it was virtually featureless. But the thought that that ball was four times the diameter of Earth gave me a rare, visceral sense of the scale of the Solar System. It can be hard to wrap your mind around the reality that the distance between Uranus and Saturn is actually greater than the distance between Saturn and the Sun. Now, at the eyepiece, it seemed obvious. I hadn't found Uranus before because I'd underestimated the size of the Solar System; I didn't imagine that a planet so big could look so small. It might seem like a drawback of manual mounts that it took me over 20 minutes to find Uranus - not to mention the many times I've searched for the planet and failed. Nothing could be further from the truth. When you do "star-hop" successfully with a simple mount, the sensation of actually finding what you're looking for is really special, and you don't get that with a go-to mount. You also start to genuinely learn the sky; I'd never thought about the constellation Cetus, for example, but now I know where it is, and I know that its third-brightest star is actually a triple-star system that I'd like to check out someday. That's not to say that star-hopping is always feasible or desirable, especially in the big city. But, as usual, you do give something up by opting for the convenience of modern technology. A last note on equipment: in recent days, I've ranked the Delos eyepieces, TEC 140, Orion 6x30 finder, DM-6, and Berlebach Uni tripod in comparison with other gear I've used. I've described them as the best I've seen in their class of equipment. Yet I haven't mentioned how well they all fit together. It really is seamless. The DM-6 holds the TEC 140 with perfect ease; there are no jitters, just buttery smooth movement even at high magnifications. The Uni tripod, while light, is an absolute rock, while the finder scope makes it a breeze to hop between stars. And the Delos eyepieces slotted in the TEC 140 provide a glorious view of just about everything. It's all very pricey, of course, but I really recommend this mix. The walk home was arduous. But, like William Herschel exactly 240 years ago, I'd found a new planet, and that made it easily worthwhile. We've had some wonderfully clear, autumnal nights over the past week, with Jupiter and Saturn riding high in the evening sky and the Moon waxing and waning nearby. I'm teaching what may be my favorite course at the moment - about the human history of nearby celestial bodies (what I call "neighboring worlds"), and a special highlight is taking my students out for a night with a telescope. I have now accumulated some very fine refractors, however, and I worried about how they'd fare after being handled by twenty students. To that end, I drew on my research funds to buy a William Optics Zenithstar 81. It's a beautiful little refractor, and I figured that it would be more than adequate to give my students an impressive view of the Moon. For their first assignment, they need to find a feature on the Moon and then write a history of how people have understood, imagined, explored, or planned to exploit that feature. A few things immediately struck me about the Zenithstar. First, it costs about a third as much as the TeleVue 85 I used to own - less than a third, when you consider it comes with its own mounting rings, dovetail, Bahtinov mask, and carrying case - despite giving up only four millimeters in aperture. Second, its build quality looks to be on par with the very best telescopes I own and have owned, with the possible exception of my TEC 140. Third, it seems to weigh less than the FS-60Q I once owned, and much less than the TV 85, and its sliding dew shield makes it much more compact than either telescope. It was really easy to carry the telescope to a darker corner of campus, and there set it up on my DM-4 mount and Berlebach Report tripod. Almost immediately, the Plossl eyepieces I'd decided to use provided beautifully crisp views of the nearly fully illuminated Moon. The students who had started to gather were predictably impressed. When we found we had a few minutes to spare at the end of the evening, I decided to try showing them Jupiter and Saturn. At about 56x, the planets were small, but beautifully sharp and clear. Many of my students were awestruck; they had a hard time believing that they could really see the major cloud belts of Jupiter and the rings of Saturn from downtown DC. Experiential learning is always special; it makes the otherwise abstract concepts we discuss in class come alive for my students, and it can provide lifelong memories. I for one was stunned by the performance of the little refractor. It is, by far, the most portable telescope I've owned, and when it comes to performance it really doesn't give up much to the TV 85. I loved my TV 85, but I would have a hard time recommending that telescope as a go-to instrument when the Zenithstar seems to provide so much more value for the cost. Last night conditions were even better, and now I resolved to head out with my biggest telescope: the TEC 140. The weight of the telescope, tripod, and mount means that I really can't haul everything to my favorite field. I targeted the little alcove next to a church that I've used over the past year, yet when I arrived as I was dismayed to find that the church had installed a new streetlight that completely ruled out observing there. I wandered about, dragging my heavy gear, until I decided to head down to a little amphitheater near the National Cathedral. There I found a perch that, if I moved around a bit, afforded me a view of Jupiter, Saturn, and the Moon through the canopies of nearby trees. When I swung the TEC to Saturn, I was mesmerized. This was only the second time I'd used the TEC, and the first time in good seeing. In those conditions, Saturn looked absolutely stunning, like a beautiful jewel set in a velvet background. Its many moons were brilliant and sharp, and the shadow of the planet on its rings gave me the rare sense that I was actually seeing a world in three dimensions (often, objects in the eyepiece look flat, and therefore two dimensional). Cloud details were obvious on the planet's yellow-white disk. Switching over to Jupiter provided an even more spectacular revelation. The TEC provided what may have been my best-ever view of the planet, with more cloud belts and zones than I could count, delicate, feathery structures within those belts and zones, and a perfectly obvious, brown "barge" - an elongated, oval cloud feature - near the planet's equator. There was a contrast and vibrance to the planet's colors that you just don't get with a smaller refractor, and all four Galilean moons were visible as clear disks, rather than points of light. Jupiter and Saturn soon wheeled behind the trees, so it was time for the waning gibbous Moon. Once again, I was dumbstruck. The Moon wasn't that far above the horizon, but at 163x there was just such a wealth of subtle, perfectly sharp detail, from jumbled crater peaks to winding rilles and delicate scarps. The terminator was perfectly positioned to throw mountain after mountain in sharp relief, and in exploring them I eventually lost track of time. Then a giant cricket jumped on my pants, I realized in shaking it off that it was past midnight, and I began packing up for the painful trek home.

The TEC 140, I have to say, is noticeably better than the APM 140 I've also raved about in these pages. I'm not sure it's worth the extra cost; certainly I could never have afforded the difference if I didn't use the telescope for my research and writing (which means I could draw from my research funds to buy it). I realize how lucky I am, and I hope I can keep using the telescope for a lifetime. It won't be that often, however, until I manage to own a backyard; as wonderful as the telescope may be, it's also hard to transport more than a few minutes from our home. Everybody approaches amateur astronomy in different ways, but for me - and many others - the most difficult thing about the hobby is that you always wonder, no matter how sublime the view: what would I see if I had different equipment? Usually "what would I see" means "what more would I see," and usually "different" means "just a bit better" - and that means that many amateur astronomers, at least at some point, embark on a long, frustrating, painfully expensive quest for new telescopes, new mounts, new tripods, new eyepieces . . . the list goes on. I've been on that path for quite a few years now. Yet when it comes to telescopes - or more specifically, to optical tube assemblies - I reached the end this spring. For a long time, I dreamed of someday - somehow - being able to own a truly world-class, medium-sized refractor. I long had my eye on the Telescope Engineering Company (TEC) 140: an American-made, oil-spaced triplet of uncompromising optical and mechanical quality that, while portable, easily outperformed much larger telescopes. I didn't think I'd be able to afford it for a very long time, but then I realized that although I'd slowly cobbled together a rather large collection of telescopes, I was really only using three of them (my EVScope, Takahashi FC-100, and APM 140). If I sold my unused telescopes and some other gear for the right price, I might just have the financial foundation I needed to pursue a used TEC 140. Precisely as those thoughts entered my mind, a TEC 140 ED in like-new condition popped up on the used market for a daunting but reasonable price. I took the plunge, and then went on a truly exhausting campaign to sell everything I could spare to recoup what I'd spent. Some of what I sold, I know I will miss for a long time. I ended up parting with my FS-60Q, TV-85, and APM-140, and each loss stings in a slightly different way. I've had unforgettable memories with the TV-85 and APM-140 in particular, but upgrading equipment is not for the sentimental. In the end I earned precisely as much money as I spent on the TEC 140, so my guilt was mostly assuaged when it arrived. Comparing it to the APM 140 was instructive and ended up highlighting the virtues of both telescopes. The TEC 140 is, first and foremost, slightly but meaningfully heaver and bulkier than the APM 140. Its focuser is more robust, its finish is of clearly higher quality, and its tube ringers are easier to manipulate. With that said, the APM's focuser is just as buttery smooth, and I actually find its sliding few shield a little easier to manipulate. It's not a tossup - the TEC 140 is clearly mechanically superior - but the APM holds up surprisingly well when you consider that it costs less than half as much (during sales, more like a third as much). Because the TEC 140 is that much bulkier than the APM 140 and uses a Losmandy dovetail that I didn't want to replace, I needed a new, sturdier mount. That's also because my AYO II mount had, after just a year, started to develop an unacceptable amount of slippage on one side. So, I scraped together what I could and purchased a DM-6 mount to match the DM-4 I purchased for my Takahashi. This, to be sure, is a beautiful piece of metal . . . but although mechanically superior to the AYO II (in my view), it's also very substantially heavier. The upshot is that my TEC 140 setup is a good deal less portable than my APM 140 setup had been. Because it's less portable, I can't take the TEC 140 to the field where I used to set up my APM. That field will be reserved for my FC-100DZ and EVScope from now on. On some level it feels like a minor loss - I had some wonderful times there with my APM - but I'm quite sure the FC-100 can pick up the slack. And I do now have the alcove, near the church by my home, that affords some fine views of the southern sky. The TEC-140 is also so heavy that I refuse to take it out unless seeing is above average. This morning, for the first time in a while, it was forecast to be. So there I was, huffing and puffing on the sidewalk at 4:00 AM, bound for the alcove and for a date with Jupiter and Saturn. Both planets have passed behind the Sun and are again high enough above the horizon to be worth a look. It was an exhausting walk, but setup was easy and quick as usual. When I turned to Jupiter, two things struck me. First, seeing was not nearly as good as advertised; that close to the southeastern horizon, it was average at best. Second, the color correction of the telescope was absolutely spot on. The older TEC 140 ED is supposed to be slightly better in longer (red) wavelengths than the newer TEC 140 FL, but slightly worse on shorter (blue) wavelengths, which should make the ED somewhat better for observing Mars and Jupiter, but somewhat worse for astrophotography. In any case, Jupiter's coloration was lovely, even if the planet's fine detail was often obscured by the turbulent atmosphere. Saturn, fortunately, was higher in the morning sky. Turning to the planet at 98x, with a 10mm Delos eyepiece installed, made for a genuine "wow" moment. Never have I seen more than a few of Saturn's moons, but now Enceladus, Dione, Titan, Tethys, and Rhea were all clearly visible. Subtle gray shading was easy to see on the planet's disk, as was a shadow just behind the rings (I love their orientation right now). The Cassini Division was plainly obvious but now around the entire ring system; unfortunately, seeing was just not good enough to see more. Once again, the color correction was sublime. After turning to some stars and observing them in and out of focus, it was clear to me that the telescope has - surprise, surprise - exceptional, beautifully corrected optics. Yet it struck me, as it did several months ago with the FC-100DZ, how much more seeing matters than optics when it comes to planetary observation. Did I see more detail this morning on Jupiter and Saturn with the TEC 140 than I would have with the APM 140? Maybe, just a little. But have I seen more detail with the APM 140 when the atmosphere cooperated? Absolutely. I'm looking forward to experiencing what the TEC 140 can do when the atmosphere truly is steady.

I suspect I will miss the portability of the APM 140, and wow that is a good telescope when you consider its cost relative to the TEC 140. Yet for me, it is important to know that the quality of my optics are not keeping me from seeing more planetary or lunar detail. With that in mind, I am very happy with my beautiful TEC. A distant goal, accomplished surprisingly soon! After two weeks of rainy, stormy weather, the skies cleared over the last two nights, and seeing conditions were, remarkably, better than average. On the evening of the eighth, I marched out of our apartment with my Takahashi, focal extender installed, to have a good look at Saturn and Jupiter. Both are now fairly high in the evening sky, beginning at around 9:00. After a fifteen-minute walk to my favorite park, I was ready to go. Jupiter, it turned out, was a little disappointing. I did manage to catch some tantalizing glimpses of complex details in the planet's belts, including one enormous ruddy patch in the north equatorial belt. But, on the whole, the colors and contrast were a little muted from what they can be. Atmospheric transparency was a little lower than average, I thought, so maybe that was to blame. Or maybe the APM 140 has spoiled me. When I switched over to Saturn, however, I was rewarded with one of my best-ever views of the planet. The Cassini Division stood out sharply along the entire ring system, and the thin black shadows visible behind the rings and on the rings, behind the western limb of the planet, were perfectly crisp. I thought I could make out no fewer than two grayish cloud belts - normally, I can clearly see just one. I admired the beautiful planet for a good long time before packing up and heading home. Then, on the morning of the 10th, I set out at 3:30 AM to observe the Moon and Mars. It's amazing what we do to ourselves, as amateur astronomers, to pursue our passion. I can never sleep well when I know I'll have to observe in the early morning, and on this night I'd had maybe a couple hours of sleep. Would it be worth it? As I left my building and set out for the park with the Takahashi, I noticed two things. First: the Moon and Mars were really high in the sky! Second: there was space in my building's illuminated "back yard" (as my daughter calls it) to set up the telescope. Why wouldn't I just do that and save myself the walk? I was awfully tired, after all. I went for it, and I can't recall making a more disastrous observing decision. After seeing up in one corner of the area, the sprinklers, which had been silent, suddenly started up exactly where I was sitting. In a panic, I grabbed what I could and rushed to another part of the yard. Nothing was damaged, but my eyepiece - a TeleVue Delos - did fog up completely. Ugh. Now I was forced to set up directly under no fewer than four bright lanterns. Maybe it wouldn't matter, I tried to convince myself. Oh, it would. Stray light kept entering the eyepiece, spoiling the view with ghostly reflections. Both Mars and the Moon also had a halo that's not usually there - partly because of the mist rising from the sprinklers, I decided. I also decided that stray light washed out some of the contrast on Mars. And what a pity, because a look at the Moon quickly convinced me that seeing was as good as it has been all year. I'm certain I made out at least a couple craterlets in the crater Plato - a sure sign of excellent seeing (and an excellent telescope). Mars was disappointing, only because it was so obvious to me that I would have seen far more had I just walked to that park. Still, dark albedo markings repeatedly shimmered into view, and the southern polar cap was obvious - if a good deal smaller than it had been earlier in the year (or have the bright clouds that make up the southern polar hood dissipated?).

Then the sprinklers turned on near me - it turns out I hadn't escaped them entirely. Why not soak pavement during the entire night? It's not like we're in an ecological crisis or anything. Once again I packed up, this time for good. All in all I was happy to have had a good look at the Moon, and grateful for the lesson - don't use the backyard! - well in advance of Mars's opposition this year. Still, after sacrificing so much sleep I had hoped for a better view of Mars. Next time! |

Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed