|

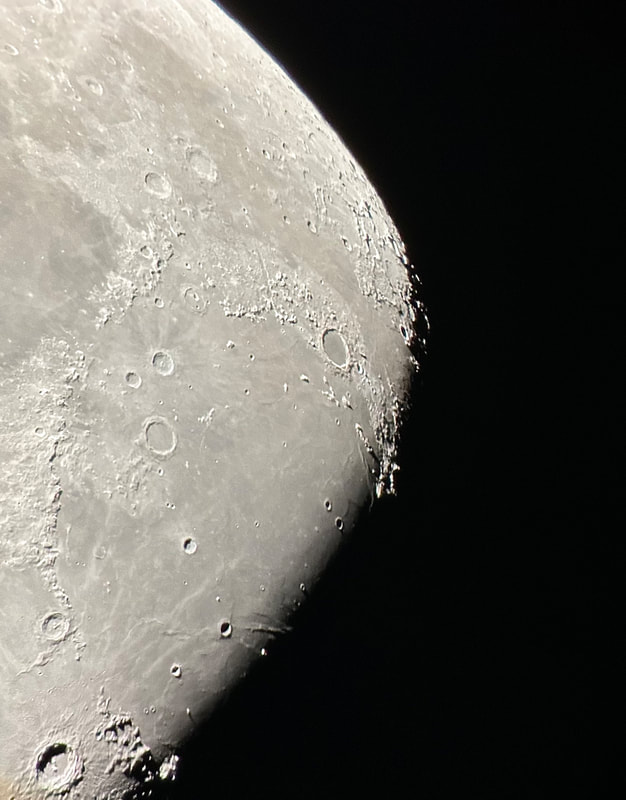

Our indefatigable news media seems to have transformed every full Moon into a show-stopping event. It's always a super blue wolf harvest something or other. To be fair, the hype stirs up a good deal of popular interest in our neighboring world, and to my mind that can only be a good thing. Of course, amateur astronomers know that because a full Moon has no shadows, it can be unsatisfying to observe with a telescope. The craters, mountains, and rilles that are otherwise so obvious seem washed out in a sea of milky-white brilliance. Still, the trees in my backyard have not yet unfurled their budding leaves, and pockets of the night sky remain visible just steps from my kitchen. The other night, I couldn't resist setting up my Takahashi TSA 120 as the full Moon moved through a gap in the bare branches. Atmospheric transparency and seeing were both about average - at least in theory. In practice, conditions seemed to shift by the minute. Occasionally a watercolor softness blurred the Moon, but then it snapped into focus for many seconds at a time. For amateur astronomers, our atmosphere truly is a fickle antagonist. Using my iPhone, I don't believe I managed to get a picture of the Moon in its clearest moments. Still, just look at those mountains outlined in sharp relief on the limb of the Moon. Rarely have I managed to get such an obvious look at them. Crater rays, meanwhile, are actually a lunar feature that becomes obvious only with the Moon fully illuminated. It was wonderful to follow their tendrils across the the Moon's silvery regolith. As for the telescope, what is there to say? Among apochromatic refractors, the TSA 120 is about as perfect as it gets. Nitpicking comes easy to me, but in this case there are no nits to pick. Actually, the telescope's size reminds me a little of the Vixen ED115S that I used to own (with its oversized Moonlite focuser). I thought the Vixen was the perfect size for a refractor, but the TSA might be even better. It actually feels a bit lighter and more compact, but the aperture is just a bit bigger. A five-inch refractor is a really ideal: it edges out the performance of a four-inch, but doesn't need a much bigger mount and tripod (which can be necessary with just half an inch of extra aperture). I recently acquired a DSV3 mount from Desert Sky Astro. This is a manual mount that isn't too heavy and seems extremely well made. It includes both slow-motion controls and a handy "quick balancing system" that allows you to easily compensate for the weight of different eyepieces. With just a flick of the wrist, the telescope stays balanced. It's a clever little feature that, I discovered last night, makes observing just that much easier.

Readers will know that I'm a manual mount aficionado. When you don't have much time to observe, or if you want to avoid all hassle in a public park, there's simply nothing better. So far the DSV3 seems like the best medium mount I've used, and I've tried just about all of them. It's at least as well made as the best mounts on the market, and it includes features that its competitors simply don't offer. For the TSA 120, it truly is just about perfect. After I'd observed for no more than 30 minutes, the Moon rolled behind my building, and with fingers numb from cold I packed up my telescope. As I've mentioned here before, it's hard to think of a better use of time than exploring another world from the comfort of your backyard.

0 Comments

Usually, the atmosphere is turbulent during our DC winters, but this winter has been an exception. The reason might have to do with atmospheric circulation rerouted by a particularly intense El Niño, but I'm not sure. In any case, winter has been unusually accommodating for amateur astronomy in the District. Yet I haven't taken out my telescopes, and I haven't updated this blog, because, unfortunately, I've found myself too sick, too overworked, or - most often - both. This month has been much better, however, and on the 18th I finally decided to give my kids a view of the halfway-illuminated Moon. I stepped out with what is now my smallest refractor - the Takahashi FC-100DZ - and quickly found atmospheric turbulence to be a little worse than average. That's perfectly okay for a DC winter, and after the telescope cooled down - in about ten minutes - it delivered a very nice view of the Moon. Unfortunately, when uploaded to this blog the picture looks a bit blurrier than it does on my desktop. But look closely at the center. That's Rupes Recta, a linear fault about two kilometers wide that cuts across some 110 kilometers of the lunar surface. Here it is zoomed in: Just below the fault are the craters Birt A and B, named after William Radcliff Birt, a nineteenth-century selenographer. Birt coordinated a network of amateur lunar observers across Britain who all sought to record changes in lunar features, which they thought would reveal the Moon to be a world similar to Earth. It's a story that I'll describe in my next book, Ripples on the Cosmic Ocean. The book is one reason I've been so busy this winter: I've finished a complete draft, and am now revising (partly by shortening). In any case, the kids enjoyed the Moon. For them, it's a neat little thing that daddy likes to show off occasionally. Of course, I try to impress them by waxing poetic about the wonder of gazing, from a comfortable little backyard, at the alien peaks and hollows of a whole other world, one utterly different from our own. They're appreciative, but hardly awestruck. I've decided that it's nice that Moongazing is so normal for them. The following night was clear again, but a good deal colder. Still, I decided to try my Mewlon 210. After letting it acclimate for about 90 minutes, I walked over to a nearby tennis court and pointed it at the Moon. Once again, I was struck by just how easy the Mewlon is to handle. It's lightweight, and you hold it by the rock-solid finder scope. It's just a wonderfully-crafted hunk of metal and glass. It's hard not to want to use it, if that makes sense. When I pointed the Mewlon at the Moon - and yes it's so nice not to have to attach and then align the finder scope - I found it was cooled down and well-collimated. Atmospheric seeing was about average, but the view was quite breathtaking. The terminator had advanced a little beyond my favorite spot on the Moon - the expanse between and around Plato and Copernicus - yet both craters retained a hint of shadow around their rims. The Mewlon gave a three-dimensional quality to the extraordinary complexity of the terrain in this part of the Moon, in particular the mountains and crater rims. The iPhone pictures I took suggest some off-center coma distortion, but I noticed nothing while viewing the Moon. I don't know what to make of that. Still, I can report that I stepped inside - hands nearly frozen - thinking that I'd be crazy to ever sell my Mewlon. On the following night - that's the 20th - I sat down to write this blog entry. Then I noticed the Moon, shining through my window. I checked and, lo and behold, seeing was supposed to be better than average - way better than I normally expect in winter. I hesitated, but of course the temptation was too strong. I stepped out with the DZ, because I needed something that cooled down fast. This time the view was truly sublime. With the Moon near zenith and the atmosphere unusually stable, the fully-acclimated DZ showed off what it can do. The view wasn't as bright as the Mewlon offered on the previous night, but owing to the steady atmosphere they were a bit more detailed. I noticed craterlets on Plato's floor with the Mewlon - a classic test of good seeing and optics - but now, with the DZ, they were more continuously obvious.

I soaked in the view for a 30, maybe 45 minutes as my fingers slowly froze. I did notice that the view routinely slipped ever so slightly out of focus, owing perhaps to the focuser with the telescope pointed straight up. But wow, that in-focus view was wonderful: among the best I've had of the Moon. I especially enjoyed the lunar maria. The picture above gives a hint of the delicate tendrils I followed across those maria: subtly different shadings, some radiating from brilliant, intricately-detailed craters. It was a lot to take in, but my fingers soon convinced me to pack up and head inside. Lunar observing is perhaps overlooked in amateur astronomy, but it truly is an incomparable experience to explore another world while standing within sight of home. Often, around this time of the year, the unstable atmosphere of winter yields to the more settled air of spring in Washington, DC. With the mosquitoes a month or two away, now is the time to observe as much as possible. The planets are all lined up at sunset, but unfortunately that part of the sky is obscured in all my nearby observing spots. Instead, for two nights over the past week, I've enjoyed a world much nearer our own. Today the sky was a beautiful, deep azure, and tonight's forecast called for good seeing with fair transparency. I decided conditions were good enough to exert a little more effort than usual. I hauled out my TEC 140 - now on a hulking Berlebach Planet tripod - and found a nook not far from my backyard. At this time of the year, budding leaves are just beginning to make my backyard unusable for astronomy. Turning to the Moon, I was disappointed - if not exactly surprised - to realize that the forecast had, again, gotten it wrong. Seeing seemed mediocre at best, and the atmosphere had that soft, milky quality that often frustrates planetary and lunar viewing. As my eyepieces and, to a lesser extent, my telescope cooled down, the atmosphere between me and the Moon started to stabilize - or, rather, it started dip into fleeting moments of clarity. Especially compelling in these "revelation peeps" - using Percival Lowell's terminology, as I've mentioned in an earlier entry - was Schickard crater, the massive walled plain clearly visible towards the center-right of this picture: Schickard's crater floor - that walled plain - was alive with irreducible detail, including countless tiny craterlets. As Eugene Shoemaker established at the dawn of the Space Age, the layering of lunar features provides a roadmap to their age. Signs of bombardment on the floor and walls of a big crater provide clear evidence that the big crater is very old. Of course, the little craters scattered around the big crater would have formed long after the big one. I love looking at the Moon as a geologist might, and I am always especially drawn to features on which observers have reported transient lunar phenomena (TLPs). Influential amateur Patrick Moore, for example, reported what seemed like a mist over Shickard just before Hitler's army invaded Poland in 1939. This time, however, all was crystal-clear. It was not my first lunar experience of the week. Several nights ago, I stepped out with my most portable setup - the Takahashi FC-100DZ on a photographic tripod - because atmospheric conditions were forecast to be mediocre at best. I'm glad I did! After I set up - with only my Baader variable zoom eyepiece in hand - I turned to the Moon and realized that, in fact, seeing was far better than average. Have a look at the picture above. Comparing it to the picture that begins this entry will reveal that, for amateur astronomers, the state of the atmosphere can be so much more important than the capabilities of a telescope. The first image was taken by a telescope that costs well over twice as much, and gathers more than twice as much light, as the one that provided that second image. Yet the second image is clearly far better. Here's a close-up of my favorite stretch of the Moon: the wonderfully diverse landscape winding from Plato (top) and Vallis Alpes down through Mare Imbrium to Archimedes, Erastosthenes, and finally spectacular Copernicus, here largely enveloped in shadow. Many of these features - or environments, as I prefer to think of them - have a rich and often bizarre history. Across some three hundred years, scientists compared them to features on Earth, speculated about their supposed inhabitants, tracked their alleged changes, and finally explored them through the voyages of crewed and robotic spacecraft.

Just look at the extraordinary detail the little Takahashi reveals - and remember that, as usual, this is an iPhone picture that blurs what is visible to the naked eye. Honestly, if you're into lunar exploring, you don't need more than a quality four-inch refractor. Seeing was forecast to be mediocre yesterday, and atmospheric transparency will below average. But the Moon rose exceptionally early - it was high in the sky by early afternoon - and therefore within range of my backyard. It had been a couple months since I was out with a telescope, owing to the turbulent winter atmosphere here in DC. I had to scratch the itch. As usual, I set up my Takahashi FC-100DZ in moments, this time with my CT-20 mount attached to the Berlebach Uni tripod. This was a lightweight but rock-solid setup, and as usual the refractor cooled down in just a few minutes. As the sky darkened to an indigo blue, I wheeled the telescope over to the Moon - and was stunned. Seeing, it turned out, was a good deal better than average - and the Moon was just beautifully sharp through my 24mm Panoptic eyepiece (which gives a magnification of just over 33x). Check it out, now at 80X with a 10mm Delos: Very striking last night was my favorite lunar crater, giant Plato, which as I've discussed in this blog was the focus of efforts to detect lunar environmental changes - and perhaps signs of life - in the nineteenth century. Many contemporary observers sought to measure shifts in the crater rim's shadows, which supposedly betrayed evidence for an atmosphere. Ever since reading their logbooks, these shadows had a special significance for me - and now I always try to see them change. No luck yet! The cluster of tiny (from our perspective) craterlets on Plato's floor are often a test of good seeing and great optics, and I think I could just make out a few of them last night. Then I wheeled over to the mass of giant, craggy craters along the Moon's southern terminator, which always provide a spectacular view. Copernicus, quite possibly the most striking lunar crater, is so impressive when the Moon is around halfway illuminated. Occasionally the atmosphere seemed entirely stable, and when it did the crater snapped into exquisite detail. Copernicus was the target of Eugene Shoemaker's pioneering, 1962 study on lunar stratigraphy, which helped unearth a kind of Rosetta stone for deciphering the history of the Moon's landscapes. Looking at the layers upon layers around the crater, now at 175x, it's easy to see why: Last night was a reminder to be wary of seeing forecasts. As I've experienced before, they can be really inaccurate - and in any case, seeing can vary from part of the sky to another. I'm going to try to avoid staying in on a clear night because bad seeing is forecast; next time that happens, I'm going to have a look for myself.

Tonight was one of those relatively rare wintry nights in Washington, DC, where atmospheric transparency is high while seeing is better than average. With Mars just four days away from opposition - its biannual closest approach to Earth - I couldn't let the opportunity slip. The canopies above my backyard are now sufficiently denuded for me to use a telescope just a few steps from my door, so out I stepped with my TEC 140. The Moon was just about to slip behind my building, and I was hard pressed to get a quick picture. The view was in fact beautifully sharp, what you see above is the only shot I could get. I also managed to get a quick look at Jupiter, where to my surprise it seemed that one moon - near the limb of Jupiter - was far below the orbital plane set by the other moons. I don't think I've seen that before. Eventually, I found a comfortable nook from which to observe Mars. Seeing seemed a good deal better than average tonight, and the outline of the planet was about as sharp and steady as I've ever seen it. I was struck by how much smaller it seemed than it did during its last opposition, two years ago, when it looked only marginally smaller than it did during its perihelic opposition of 2018. Of course, my gear has improved since then, so the views of Mars I've had this year haven't been much worse than those I had in 2020. Still, the planet's apparent diameter is only about 17 arcseconds this year - down from 22.4 in 2020, and a whopping 24.2 in 2018. In fact, not since 2014 has Mars looked so unimposing at opposition.

More important for viewing Mars than the apparent size of the planet or my equipment, however, has been dust. In 2018, I couldn't make out any details on Mars while using my Skywatcher 100ED, and that owed more to a yellow, planet-wide dust storm than the lack of perfect color correction on the refractor. In 2020, Mars was relatively dust-free, and so a deeper shade of red. I was ready then with a pair of telescopes (my dearly departed APM 140 and Takahashi FC-100DC) that were only slightly less capable than those I own today. Now Mars seems dusty and a bit yellowish again, but not as much as it was in 2018. Surface detail has obvious through my TEC 140 and Takahashi FC-100DZ, though not as much as it was in 2020, and the planet's disk is comparatively small. I replaced my APM 140 with the TEC 140ED, and my FC-100DC with the FC100DZ, in large part to prepare for this year's opposition. I'm glad I did, but in making those replacements I've also come to realize that there really are rapidly diminishing returns for costly upgrades in this hobby. Yes, views through the DZ seem marginally better than the ones I enjoyed with my wonderful DC, but from night to night conditions in our atmosphere - and that of Mars - are much more important. Tonight I was again reminded of how trifling differences in performance between optics can be enormously exaggerated in online discussions. It's widely held that high-contrast eyepieces such as the TeleVue Delos will easily outperform zoom eyepieces, including the latest iteration of the Baader Hyperion Zoom. While switching between the zoom eyepiece and the Delos 4.5mm and 6mm eyepieces, however, I found that magnification affected the view far more than the eyepiece I was using. The view seemed just right at around 160x; any more than that, and it got a little blurry. Both the Baader and TeleVue eyepieces provided striking and at times rather complex views of Mare Cimmerium at that magnification, along with flashes of Trivium Charontis and perhaps some other dark regions in the northern hemisphere of Mars. I thought I might have caught some hints of white swaths far to the south, but they were hard to pin down; I fancied they might be clouds. I saw very little to separate the eyepieces, but I eventually found myself settling with the 6mm Delos because of its larger field of view. If pressed I might confess that dark albedo regions were more consistently obvious in the Delos than the Baader Zoom - but that may be only because I expected to see them more clearly in the Delos. One thing's for sure: I'll never again assume that I'm missing out by using the zoom eyepiece as opposed to a Delos, and I'll be a little more careful when reading claims that one premium eyepiece or telescope is clearly superior to another. I hope to have another chance to observe Mars this week, and certainly this month, but if not tonight was a wonderful way to mark the planet's opposition. Autumn came early this year in Washington DC, yet the relative warmth of early autumn lingered well past its usual expiration date. The mosquitoes lingered with it, even if their population fell with the leaves, but overall it's been a gorgeous month in the city. Over the past week, we had three crisp, clear nights with tolerably good seeing and transparency. With the canopies above my yard increasingly bare, I was able to peak through and branches and observe without hauling heavy gear for twenty exhausting minutes. A few nights ago, I rolled out my TEC 140 to observe the Moon and Jupiter. Night comes early at this time of the year, of course, so I made it outside before my six-year-old daughter's bedtime. I asked her to join me, and when she did she was thrilled to make out craters on the Moon and, with some difficulty, cloud bands on Jupiter. To my surprise, those were unusually difficult to make out. The sky had a milky quality around bright objects, a kind of watercolor softness, that seemed to obscure detail on the likes of Jupiter. Still, a memorable experience for daughter and daddy alike. On November 8th, conditions promised to be marginally better, and temperatures were just about ideal. This time, I stepped out with a much lighter setup: my Takahashi FC-100DZ, clamped to the CT-20 mount that I'd screwed into my Berlebach Uni tripod. It's a more robust outfit than I take to the local park, but it's still easy to move all in one go. A quick aside: the exceptional weight of the DM-6 mount can make it really sturdy and capable of handling surprisingly hefty telescopes. Yet it also ruins the portability of my TEC 140. The mount feels at least as heavy as the telescope, and when yoked to a tripod it's a chore to move even without the telescope attached. Another problem is that attaching the telescope to the DM-6 mount is a heart-stopping experience in the dark. It's hard to be sure that the dovetail is actually in the clamp, and I've now been unpleasantly surprised several times when the telescope suddenly lurched down after I thought I'd got it in. I live in fear that on some sad night I'll misjudge it, step away, and watch in horror as the telescope crashes to the ground. I have no such problem with the Takahashi. Yet the lightness of the CT-20 mount does mean that the telescope tends to tilt - even when perfectly balanced - if objects are too close to zenith. The CT-20 has an answer, however: it's easy to adjust the tension in the altitude and azimuth axes. This can mean that there's too much tension to easily nudge the telescope along when observing objects that are high up in the sky, but I'll take the tradeoff: less weight and less hassle is worth some compromise. In any case, the Takahashi gave me some very satisfactory views of the waning but still nearly full Moon. The view along the emerging terminator in particular was quite striking, while the Moon's fully illuminated surface showed a mesmerizing swirl of subtle grey shadings. The rays streaking from Tycho, one of the youngest big craters on the lunar surface, are always impressive when the Moon is this close to full. Yet Mars is now wheeling towards its biannual opposition, so of course it stole the show. The planet is quite high in the sky by around 10 PM EST, and it's already brighter than any celestial body visible at that time save Jupiter and the Moon. I feel that its color even by naked eye is not quite as blood-red as it was two years ago; it's paler and a little closer to orange. The Takahashi revealed its waxing globe, but showed considerably less contrast than I could make out a couple years back. In moments of good seeing I could make out the south polar icecap, and then a dark albedo swirl around the ice, interrupted by lighter land before continuing towards the north. Yet the view was anything but sharp, and the planet seemed unsteady somehow in the mediocre seeing. Part of the problem is that much of Mars is currently obscured by bright dust storm: a common if frustrating occurrence when Mars makes a close approach to the Sun. It was to gain a clearer view of the Moon and Mars that I stepped out last night with the TEC 140. Conditions seemed about the same, except it was colder and the reappearance of a halo around the Moon suggested that transparency would be lower. The TEC takes meaningly longer to cool down than the Takahashi, although in both cases the Delos eyepieces take longer to acclimate than the telescopes. I'm not sure it's widely understood that compound eyepieces take longer to cool down than, say, Plossl eyepieces - but that's certainly been my experience, and it does stand to reason. There's just a lot of glass in those things.

In any case, both refractors and their eyepieces need only a few minutes to give acceptable views, even if they do take longer to fully acclimate. When everything was ready I was surprised to find that the TEC 140 actually provided slightly softer views than the Takahashi did the other night, even if contrast on Mars in particular seemed just a bit higher, and the Moon's terminator at times snapped into exquisite if fleeting focus. I was once again impressed by the Takahashi; despite its compact size, I rarely feel I'm missing out when I use that telescope, the way I did with many other small telescopes I've owned. It punches far above it weight. Yet to me the bigger takeaway was that the difference between telescopes is often completely swamped by atmospheric conditions. In mediocre seeing and transparency, there really isn't much of a divide between the $8000 (!) TEC 140 and the $3000 Takahashi (of course both telescopes have world-class optics; even in bad seeing, I would suspect a meaningful difference between them and a run-of-the-mill refractor). In my years of observing here in DC, I can probably count on one hand the nights on which the atmosphere was so stable and clear that I could use magnifications of 200x or more. The pricey difference between optics is often less apparent here than it would be elsewhere, and I think that's something observers should acknowledge more often. Where you live will dictate the gains you get by spending more on bigger and fancier telescopes. William Sheehan - who publishes some of the most engaging books on the history and practice of planetary and lunar observing - writes that as an observer views Mars near opposition, "over it, intermittently, uncertain details dart and then are gone like doubtful visions." None other than Percival Lowell - a key popularizer of the Mars canal theory, among other things - coined the term "revelation peeps" to describe these sudden glimpses of intricate detail. That is precisely what Mars had on offer tonight. It wobbled and wavered, like a coin seen through the burbling water of a fountain. Then, for fractions of a second, it snapped into sharp relief, looking really and truly like a planet seen from an approaching spaceship. Just before my brain could grapple with that new reality, the planet reverted so quickly to an indistinct blob that I could scarcely believe it had ever been otherwise. Mars! Always so difficult, but oh so compelling. Earlier this month, I set forth on a night of above-average seeing to the field that has become my favorite observing spot, just an eight minutes' walk from our new home. I heaved up the hill bordering the field, hauling my Takahashi and an uncomfortably heavy backpack, full of expectations. As I rounded the top of the hill, I saw . . . this. It's one thing to install new lights, but these were about the brightest I've seen in Washington, DC. I could scarcely believe my now not-at-all dark adapted eyes. Another observing spot - my third, since this blog began - ruined by newly installed, fluorescent lighting. It's demoralizing to experience firsthand how every patch of dark sky in the city is steadily being surrounded and at last consumed by unnecessary light. I wandered home, too stunned, too sore, and too tired to find another location to set up. In the days that followed, I reviewed my options. I wandered around my home, and found another location, in a neighborhood garden, just a bit farther than the field - but a lot more overgrown with bushes and trees, and no doubt overrun by summer bugs. Then there was another field, perhaps a 20-minute walk away, and (for now) dark at night. Wherever I went, it would be farther: and I had trouble enough walking the eight minutes to the now unusable field. I decided I had to reduce the weight of my grab-and-go setup, and in particular ease the strain on my shoulders. But how? MY DM-4, I thought, was about the lightest mount I could use with my Takahashi FC-100DZ. I agonized over whether to exchange the telescope for something smaller and less capable. I bought it in the first place because it was the biggest and best telescope - that cooled down quickly and provided spectacular lunar and planetary views - I could easily walk with for 10 or 15 minutes. But 20 minutes? And with the mount I needed, and my eyepieces? Eventually I figured that the step down to something smaller - a Takahashi FC-76 DCU, for example - was just too big a fall to be worthwhile. Since my tripod is already wonderfully light, I was left with my eyepieces and mount. The eyepiece problem was easy to solve. Rather than carry four Delos eyepieces, I decided to take just one eyepiece with me: a Baader Mark IV Variable Zoo. When equipped with its barlow lens, it would give me all the magnification I could want. There was a cost: a marginal loss in sharpness, perhaps, and a meaningful loss in field of view (which means something with a manual mount). Still, I found it a small price to pay compared to the alternative (swapping telescopes). I also started researching mounts. Readers will know I settled on the DM-4 after using an AYO II mount. Both mounts are impressive. The AYO II is lighter than the DM-4 and more compact, even as it seemed less durable. Now I wondered whether to exchange the DM-4 for another AYO II; weight, it seemed to me, had to come first. However, I soon found some intriguing newcomers in the quality manual mount market. One in particular stood out: the CT-20 by NoH's Mount, a little company owned by an independent craftsman in South Korea. On paper, the CT-20 weighed less than half as much as the DM-4 (and a third less than the AYO II), while being more compact than both. It cost less and handled more weight. It seemed almost too good to be true - but I bought it, and sold the DM-4. To my surprise, on the night the CT-20 arrived from South Korea, the sky was clear and both seeing and transparency were well above average. I greedily unpacked the little mount, hoping I'd be able to use it immediately. I was immediately impressed - and, to be honest, a little surprised - to find that its build quality seemed exceptionally high, on par certainly with the AYO II and DM-4. I was also delighted to find that the mount is even more compact than I'd expected (this is a rarity in amateur astronomy, where things tend to be much bigger than you thought they'd be).

This time I packed my mount and eyepiece into a much smaller, more comfortable backpack; all in all, I think I shaved about ten pounds from the load I had to carry. I walked the 20 minutes to the more distant field, and was delighted to find that I still had some energy left - and that the field was mercifully dark. I unpacked, set up, and to my astonishment soon found the mount at least as stable with the Takahashi as the DM-4 - and that without the vibration suppression pads that I used with the bigger mount! It also allowed my telescope to easily clear my tripod; with the DM-4, I'd needed a ($250!) tripod extender for that. I quickly slewed to the Moon, and there encountered another surprise: a stunningly sharp view of the lunar terminator in the best seeing I've experienced all year. The mountains on the lunar terminator in particular took on a gloriously three-dimensional character, and I easily made out countless subtle rilles and scarps. Rupes Recta, the so-called "Straight Wall" of the Moon, was perfectly illuminated and a particularly striking sight. I got a genuine sense - maybe for the first time - of how eighteenth- and nineteenth-century astronomers could have mistaken rectilinear features on the Moon for signs of intelligent life. I'm not sure a Delos eyepiece would have afforded a better view; in fact, I couldn't imagine a better view. Next up was Jupiter, and wow: what a sight. I have never - not even with my TEC 140 - seen the planet's Galilean moons look so clearly like colorful discs: like perfect little worlds, clearly distinct from stars. The planet's cloud belts and zones were phenomenally complex, with countless delicate filaments intruding from the dark belts onto the milky-white zones. The planet's southern hemisphere in particular boiled with complexity, especially in moments of seeing so good that the terrestrial atmosphere seemed simply to disappear. I observed the planet for a long time, spellbound. It was thrilling not only to feel so close to that alien world, but also to know what the Takahashi (and my entire grab-and-go kit) is really capable of. Then a sprinkler went off in the distance. It was too far to worry me - until I realized that another sprinkler could well be waiting under my feet. I quickly packed up and made my way back home. I'll come back to that field, sprinklers and all - but now other locations seem in reach, thanks to an unheralded little mount that may just be the best I've ever used. Binoculars have long frustrated me. While I've thrilled at catching glimpses of rocket launches or lunar craters with big Celestron binoculars here in Washington, DC, I could never hold them steady enough to make out more than blurry glimpses. I opted for more manageable binoculars, but still: no matter what I did, the view was always disappointing. Eventually I gave up and decided that binoculars were just not for me. Then I learned about image stabilized binoculars: remarkable little devices that use gyroscopes and moveable lenses to cancel the inevitable vibrations caused by human hands. The high cost and relatively small size of these binoculars at first convinced me that it just wouldn't be worth it to buy one. Eventually, however, I found that I'd accumulated a heap of eyepieces I no longer used, and after selling them I took the plunge. I bought a pair of Canon 12x36 Image Stabilization III binoculars. When they arrived, I decided to try them out on the abundant birds in my backyard. I'm not a bird watcher - the one time I went on a bird watching tour at a conference, I was nearly abandoned in the middle of a desert - but I have to say, I was absolutely floored by the view. It really felt like the bird I was looking at - a female cardinal high up in the canopy - was right there in front of me on the table. The view was absolutely crisp, razor-sharp with no false color, and better yet: it was stable. It's hard to emphasize enough what a difference that makes. I was eager to see what I could make out on the planets, which had become very prominent in the mornings. When I tried, however, I was disappointed. This time I noticed some false color, and the image wasn't quite sharp enough for me. I figured, sadly, that even the best binoculars might not have much value for me in astronomy. Yet last night I couldn't resist the temptation to try out the binoculars one more time. The last "supermoon" of the year was rising, the Perseid meteor shower was peaking, and I really wanted to go to my favorite park. It's a long and painful hike with a telescope, but easy and fun while riding a scooter with one-pound binoculars in a backpack. I zipped out at around 11 PM, and made it to the park in no time.

The very first thing I saw as I reached my preferred observing spot was a bright meteor: an auspicious start if ever there was one. When I looked at the huge, golden Moon, however, I was again disappointed: it was just a bit blurry, with too much false color. This time I carefully adjusted the binocular's collimation and focus, waited a few minutes for it to acclimate, and tried again. What a difference! Now the Moon was wonderfully sharp - like those birds in my backyard - and to my astonishment the view really wasn't much less impressive than it is with my Takahashi refractor at low magnifications. The amount of detail I could make out was nothing short of miraculous. Then I turned to Saturn, and could hardly believe it when I easily made out its rings. Jupiter was rising above the horizon, and sure enough: there were its moons, perfectly clear in binoculars with an aperture of just 36mm. There was something exhilarating about how easy it all was. The binoculars are little bigger than my hand, and of course they required essentially no setup. But there I was, with bats fluttering overhead (I saw one through the binoculars), admiring the heavens. After about 15 minutes, I had that giddy feeling I sometimes get during my best nights under the stars - and since I wanted to leave on a high note, I hopped back on my scooter and sped home. Image-stabilized binoculars cost a lot more than a decent pair of regular binoculars (but a lot less than premium binoculars with high-quality optics). However, I'm now convinced that it's difficult to compare them to their lower-tech cousins. It's a completely different experience to use them. Because their views are stable, looking through them is more like using a telescope than regular binoculars - with the added benefit of the three-dimensional experience that binoculars (or binoviewers) uniquely provide. I have a real weakness for little instruments that provide outsized views (it's why I loved my TV 85 as much as I did). After last night, I have to conclude that the diminutive Canon 12x36 is, quite possibly, the most impressive optical instrument I've ever tried out. It doesn't often work out this way in amateur astronomy, but sometimes big things really do come in little packages. Here in DC, it's hard to avoid thinking obsessively about the demoralizing news from eastern Europe. Yet the skies cleared recently, enough for an hour or two of late-night escapism. A few nights ago, I slipped out with the Takahashi. Transparency was really good but seeing was far worse than average, and since it was well below freezing I didn't want to stay out for long. Still, the FC-100DZ performs so well in poor seeing that I still managed to have a nice view of the waning Moon from my new backyard. Conditions were similar last night, with good transparency and poor seeing. By 10 PM the Moon was only just beginning to rise, which means that the sky was still quite dark. The Big Dipper was climbing towards zenith, and that gave me a chance to image Bode's Galaxy - M81 - with the EVScope 2. I tried imaging M81 with the EVScope 1 on several occasions last year. I have a particular fascination for barred spiral galaxies like M81, which at 12 million light years away is a little smaller than our galaxy. I'm not sure where that comes from exactly, though the shape is certainly aesthetically pleasing. As a kid, I vividly remember admiring a picture of a barred spiral - was it NGC 1300? - that really captured my imagination. Then I found out, when I was a little older, that our own Milky Way was actually a barred spiral, not the conventional spiral it's usually portrayed to be. That was a fun little eye-opener for me. In any case, observing Bode's Galaxy with the EVScope 1 was a disappointment for me. The galactic nucleus is bright enough, but the spiral arms are subtle and easily lost in the downtown DC light pollution. I never got much more than a blurry circle. The EVScope 2 allows me to take longer exposures, however, and that plus its higher resolution made me hopeful of a better outcome last night. And indeed, this is far better than anything I managed with the EVScope 1. To capture this 26-minute exposure from my backyard in downtown DC, after just a few seconds of setup time, seemed borderline miraculous to me. This time, I also peered through the new and improved eyepiece of the EVScope 2. What a huge improvement! Looking through the eyepiece of the original EVScope was like looking down through a barrel at a tiny, pixelated square. But the eyepiece of the EVScope 2 feels like . . . well, a proper eyepiece. The view is circular, it feels close, and it's noticeably higher resolution. In fact, it looks more impressive than the image above. The gallery above shows the difference between unprocessed 9-minute, 18-minute, and 26-minute exposures. The difference is subtle, but it adds up. Note the relative lack of a diffuse glow around the galaxy. With the EVScope 1, that glow used to creep into my exposures after a few minutes, as a result of light pollution here in DC. That's one reason that my views were so much better out of the city. The EVScope is much better at filtering out light pollution, which makes it a far more capable telescope for deep space observing in the city.

When I ranked the telescopes I'd owned last September, the EVScope 1 came it at number 7. I'd rank the EVScope 2 a good deal higher - definitely in the top five, maybe even the top three. It's that good. With a backyard, I'm able to do something I don't think I've ever tried before: observe the Moon before sunset. I just could never imagine doing that in my old home. On my former rooftop, I might have been besieged by my neighbors, and in a nearby park, hounded by dogs. But now, at last, I can relax behind a fence, set up a nice refractor, and enjoy the Moon at my leisure with a beer in hand. It's beautiful. During my move, I'd noticed that the focuser on my Takahashi FC-100DZ had a little too much give. The culprit, I realized, was a loose screw. Repairing this little issue led me to consider upgrading other aspects of my grab-and-go setup. I parked the telescope inside to attempt to quantify the vibrations I'd long experienced with the Berlebach Report tripod I'd been using. It didn't take me long to realize that, even in a completely wind-free environment, those vibrations were intolerable at high magnifications. I will still need to walk to the parks I've often frequented - my little backyard only reveals so much, and the pockets of sky I can access will close when the trees regain their leaves - so I started wondering: did I need to sell the DZ for a lighter telescope? I hated the idea, but I certainly don't want to haul around the tripod I use with my TEC 140 just to use a four-inch refractor. Uncharacteristically, I wrote a note asking the CloudyNights community for help, and help I received. Carbon fibre mounts, some of the responses stressed, could yield fewer vibrations than my wooden mount. This seemed counterintuitive to me - wood, I thought, tends to dampen vibrations - but I went ahead and purchased an Innorel RT90c Carbon Fiber Tripod. I was skeptical, but sure enough: the tripod just about halved the vibrations I'd experienced. It's also much lighter and more compact, meaning that I now have a more portable and more stable grab-and-go setup. Best of all, I get to keep the DZ: a telescope I love. I took the above picture of the waxing Moon a couple days ago (February 9th), at around 5:00 PM. At the time, seeing was worse than average, but transparency quite good. Note how much lunar detail the FC-100DZ reveal in even poor seeing; it's quite remarkable. Observing at 5 PM gave me a chance to, at long last, share my passion with my kids. My eldest is 5, my youngest 2. Both insisted that they could see craters, though my daughter claimed that the Delos eyepiece was a little hard to use. And it's true: it takes a little practice to know where exactly you should position your eye with a big, complex eyepiece like that. I wonder whether a simple Plossl eyepiece would be a better bet for the kids - and for outreach more broadly. It's what's I use with my students (admittedly, partly because I don't want to risk my pricier eyepieces). It clouded over that night, unfortunately, so I wasn't able to observe after sunset. Yet when I stepped outside the next night to get some air, I realized to my surprise that I could see the Moon setting in the west behind my building. Clouds were rushing in, and the temperature was falling fast. Before my move, I would never have observed in those conditions. Yet now it took me all of three minutes to pop inside, grab my Takahashi, and set up everything up in the only corner of my backyard that still afforded a view of the Moon.

Neither the telescope nor my eyepiece had cooled down, and seeing was atrocious: about as bad as it gets in DC. But as the picture reveals, there was still plenty of lunar detail to be seen. The Takahashi excels in good seeing, but I've also found - like others - that it manages to outperform just about any comparable telescope in poor conditions. I'm hopeful that, in late fall, winter, and early spring, I'll be able to use my backyard to study the Moon far more consistently than I ever have before. In that effort, I suspect the FC-100DZ will be my most important tool. |

Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed