|

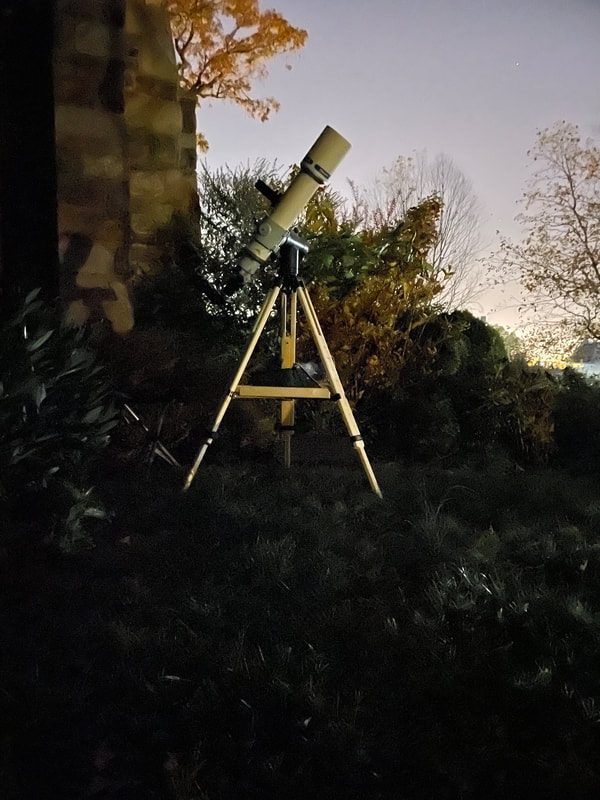

We've had some clear skies over the past week, and of course for me that involved hauling my telescopes outside. With Jupiter and Saturn high above the horizon early in the evening, now is a great time for planetary observation. I set up my Takahashi FC-100DZ on our rooftop one night, but although it was convenient - and the National Mall looked spectacular in the distance - plumes of heat rising from our building marred the view. Jupiter was a boiling mess, and Saturn looked only slightly better. Smoke from the west coast wildfires moved in early this week, so the transparency of the sky plummeted. Yet seeing was above-average, and - knowing that a little haze in the sky can sometimes improve planetary views - I stepped out anyway, Takahashi in hand. I mount the telescope on a DiscMounts DM-4, and although the mount should easily be able to hold the Takahashi with minimal vibration, so far its stability doesn't compare to that of the AYO II I recently sold - even on my heaviest tripod. Perhaps I need to play around with the tension? I suppose I'll keep experimenting. I wasn't prepared for the thickness of the wildfire smoke at high altitude - yes, that's more than a little depressing - and so Jupiter and especially Saturn were dimmer than I'd anticipated. Yet seeing was, at times, phenomenal. All of Jupiter's moons were visible, and all looked like clear disks of varying color and size. Orange Io and giant Ganymede were especially easy to pick out at 177x, and for once I wished I had more magnification (unfortunately, I'd left my Nagler zoom eyepiece at home). On nights of bad seeing, one two dark belts can be visible on Jupiter. Now, I saw some spectacular detail. Not only were the two northern and two southern temperate belts plainly visible, but I could make out delicate, at times feathery texture all along each belt. I lingered a while on that view. Saturn, unfortunately, was less impressive: the smoke was just too thick to permit more than a dim view. On a night with higher transparency, I walked out with my EVScope. I confirmed what I'd long suspected: in a light-polluted urban sky, brightening at the edges of the view precludes long exposures. While you can still get impressive urban (!) views of many nebulae, star clusters, and galaxies, the telescope performs much better when the light pollution isn't as bad.

The comparison above shows what the EVScope can do under a suburban sky (top) and in ideal conditions under an urban sky (bottom), with similar exposure times. It should be stressed that conditions for the bottom image were truly ideal: the nebula was near zenith, there was no Moon, and transparency was excellent. Still, it's clear that the telescope goes a bit deeper when the light pollution is lower. Of course, I also could have had a much longer exposure under that suburban sky, had I wanted to do that. All in all, two good nights of very different observing - and one pleasant view from our rooftop.

0 Comments

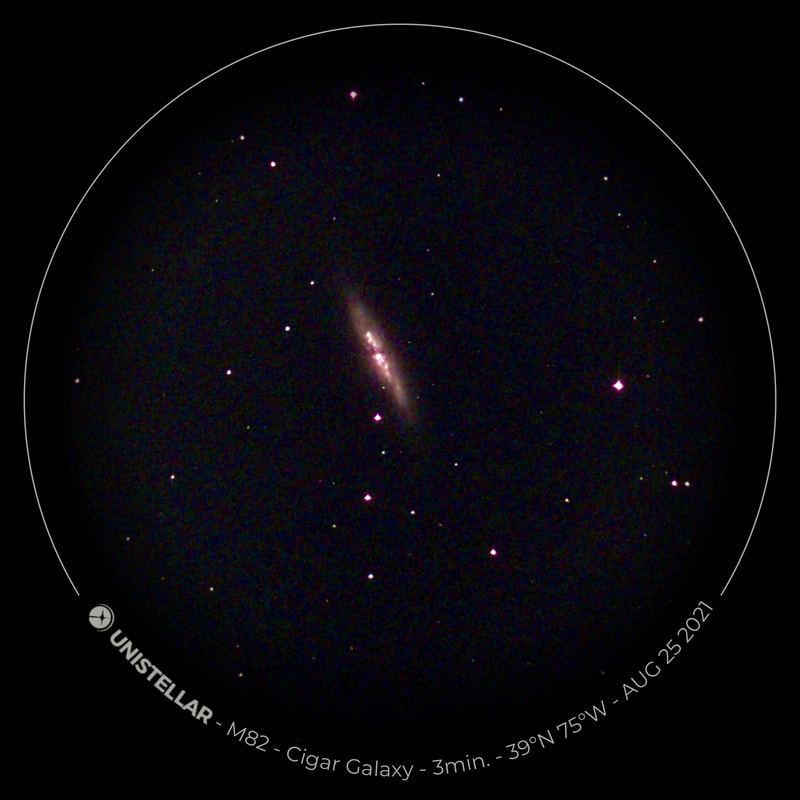

Another clear night on the Atlantic Coast, again with good seeing (but mediocre transparency). Once again I quickly set up my EVScope, and this time I had eyes on the galaxies in the Big Dipper, towards the north, and the Nebulae around the galactic core in the south. The galaxies turned out to be a little disappointing, partly because the EVScope's "enhanced vision" - its image-stacking mode - kept cutting out after just a few minutes. I've had a spotty and unpredictable wifi signal here, which might be to blame. Light pollution is also worse towards the north, and the Big Dipper was low on the horizon. The nebulae to the south, however, were nothing short of spectacular. Below (clockwise from top left) are the Lagoon, Omega, Trifid, and Eagle nebulae, in five- to 10-minute exposures. What really strikes me is the amount of subtle detail in each of these short exposures, especially the dark lanes weaving through each nebula. I took all of these shots, collectively, in about 30 minutes - and then packed up my telescope in around 10 seconds. So, another successful night here in Lewes, Delaware. Now it's back to our light-polluted skies in DC, where my next targets will probably be Jupiter and Saturn.

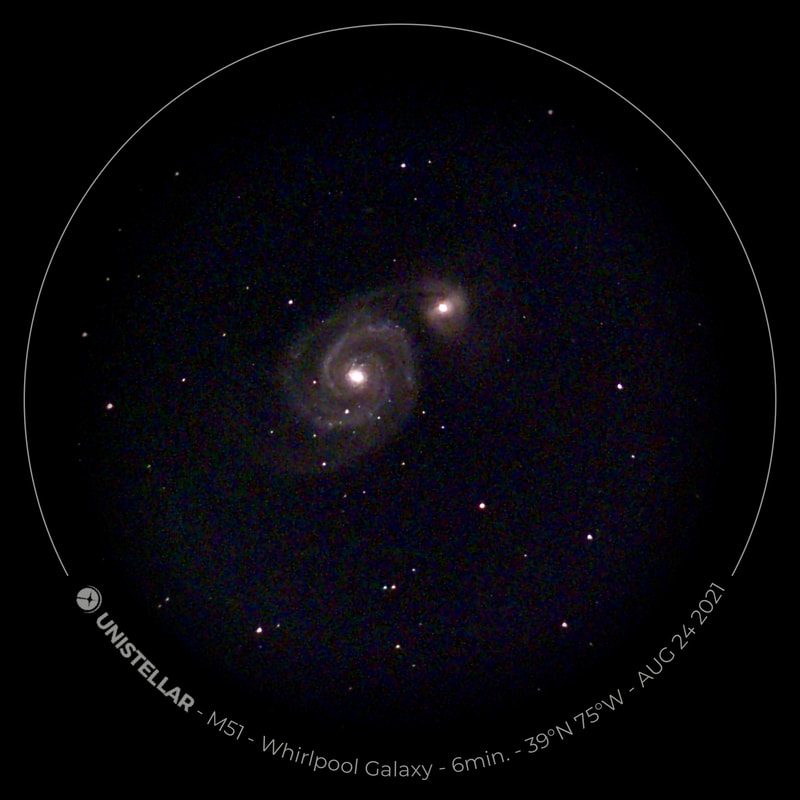

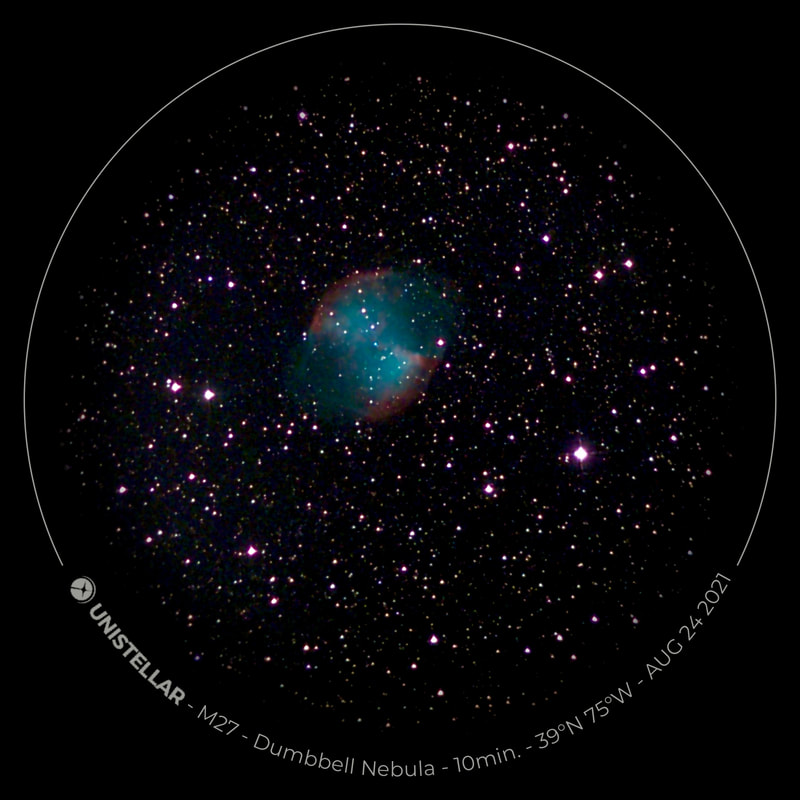

It's been boiling hot and cloudy at night through much of July and August in DC, but this week we escaped to the Atlantic coast. I asked my five-year-old daughter which telescope I should bring, and though Jupiter amd Saturn are high and bright right now she was adamant: the one that would give the best views of nebulae and galaxies. Though I was tempted to bring my TEC 140, the EVScope was the clear choice. I set up the little telescope beneath skies in Lewes, Delaware, that were just about dark enough to reveal the Milky Way. Seeing was really good and transparency was about mediocre. While lying on a hammock in the sun room, I controlled the EVScope and slewed it from one target to another, checking its progress on my phone. You just can't beat that convenience. When there's a lot of light pollution - as in DC - I quickly notice a brightening at the edges of the screen when taking EVScope exposures that are more than a few minutes long. No such trouble here in Lewes, where the light pollution is not comparable to what it's like in DC. I realized things were different right away, with this exposure of the Whirlpool Galaxy. I've written this before, but wow what a thrill to set up a suitcase-sized telescope and, within minutes, observe nebulae in a galaxy 30 million light years away! The more I use the EVScope, the more I find myself thinking that telescopes like it represent a huge part of the future of amateur astronomy. Light pollution is unlikely to get much better any time soon, and attempts to reduce future warming by increasing the opacity of the atmosphere are becoming increasingly plausible (this is known as solar geoengineering). Electronically assisted astronomy (EAA) will help observers overcome these obstacles - while giving them views of the distant universe that simply can't be matched with traditional optics (at least not in a portable package). The technology will only get better, and I can imagine telescopes that can switch seamlessly between modes ideal for Solar System and deep space object observation. While the EVScope can deliver impressive views within the biggest cities, it dawned on me last night that it really comes into its own under darker skies. Perhaps it's no surprise that even EAA follows the same principle as traditional astronomy: the darker the sky, the better the view. The EVScope only reduces - enormously - the usually extreme difference between dark-sky and polluted-sky observing. For example, I've been trying to get a good shot of the Dumbbell Nebula for the longest time in Washington, DC, but whenever I tried I ended up with little more than a disappointing blob. But just look at the view after just 10 minutes in Lewes. To me, the level of detail and color is nothing short of phenomenal. And what a thought: the Dumbbell Nebula is illuminated gas released by a red giant star before its collapse into a white dwarf (in this case, the largest white dwarf known to astronomers). This is what our Solar System could look like in six billion years or so. So yes: when it comes to the EVScope, it's hard to beat the views. And it fits in a tiny corner of my car's trunk, tripod and all!

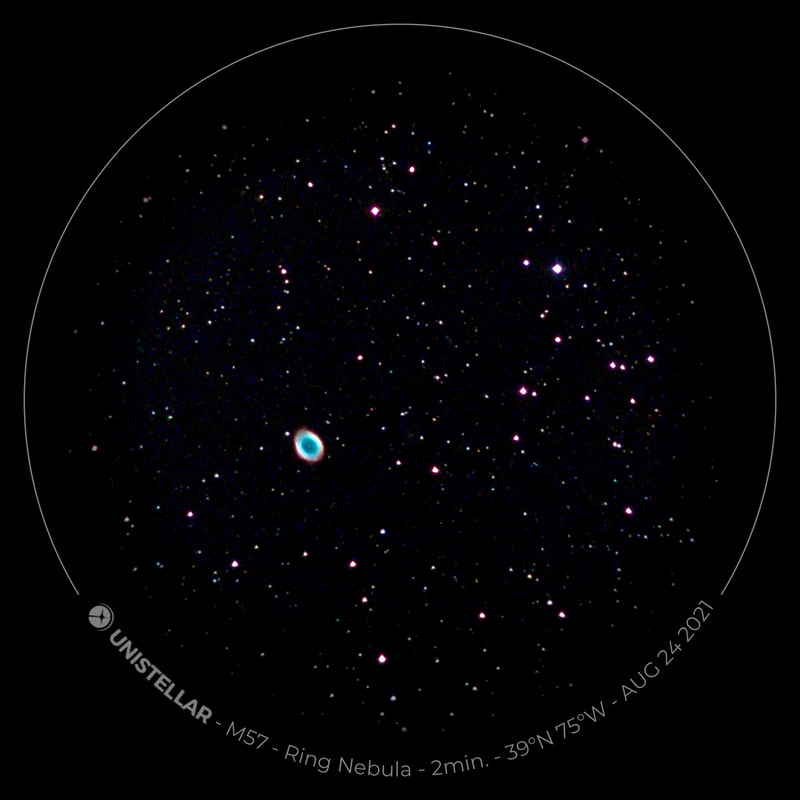

I've written about the EVScope and Electronically Assisted Astronomy (EAA) quite frequently in these pages. I was skeptical at first - partly because my EVScope had a technical problem - and only came around slowly. Only last night did I become an enthusiastic supporter. I stepped out on a warm, breezy night with the EVScope in its backpack. Transparency and seeing were both around average; there was no Moon. When I reached our nearby park, I set up in all of 30 seconds. I decided that my first target would be the Eagle Nebula, which I've never glimpsed through a regular telescope. The galactic core was lost in light pollution over the National Mall - the sky seemed closer to white than black - so I wasn't optimistic. And yet! When the EVScope found its target - in just a few moments - and started gathering light, a multitude of stars snapped into view, and then the nebula. After a couple minutes, light pollution started to cloud the view - I haven't tried to tinker with the settings that could help me resolve that issue, not yet - so I stopped the exposure after eight minutes or so. I was left with this: In the dark, on my phone, it looked spectacular. Look! There are the pillars of creation - star-making factories so memorably imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope - somehow visible from downtown Washington, DC, just nine or so minutes after setting up in an urban park. This image does it for me - I like my nebulae ghostly and ethereal - but with a little image processing, even more detail pops out (see the picture at the beginning of this post). Now it was on to the Trifid Nebula nearby, it too lost in downtown pollution. Not for long! Again, I'd never seen it with a regular telescope, yet again, it didn't take long to pop into view through the EVScope. This image I like a little less; the unprocessed version doesn't quite bring out the blue. Still, getting this detail so easily in the middle of a city feels nothing short of miraculous. Then it was off to the Ring Nebula which, of course, never fails to impress - albeit in very different ways through an optical versus an EAA telescope. Whether because of a software update or an unusually transparent sky - I suspect the former - I was, for the first time, able to see the white dwarf at the heart of the nebula. Seeing that would require an enormous regular telescope - too big for my car - and a very dark sky. Imagine my wonder at glimpsing the dead star from the city: our Sun's future, six or seven billion years from now. I didn't have much time left, but I wanted to see how far I could reach. I turned to NGC 5907, a galaxy marginally larger than our own, around 54 million light years distant. I could only take a short exposure - I really did have to leave - but there: an edge-on spiral galaxy that I would never have been able to observe even with my TEC 140. The light in this picture left its source not only after the dinosaurs went extinct. What a thought!

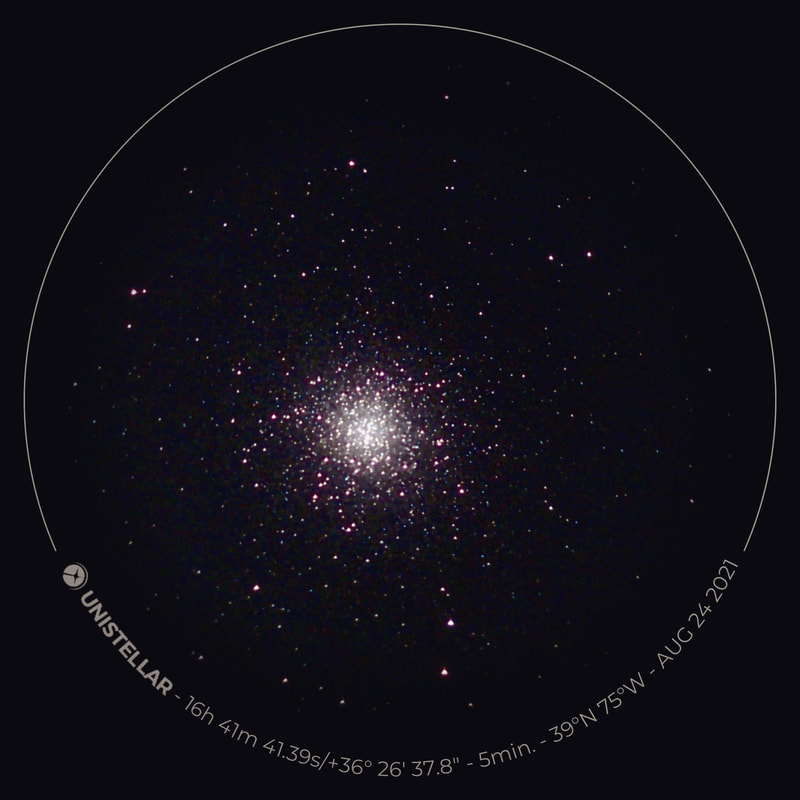

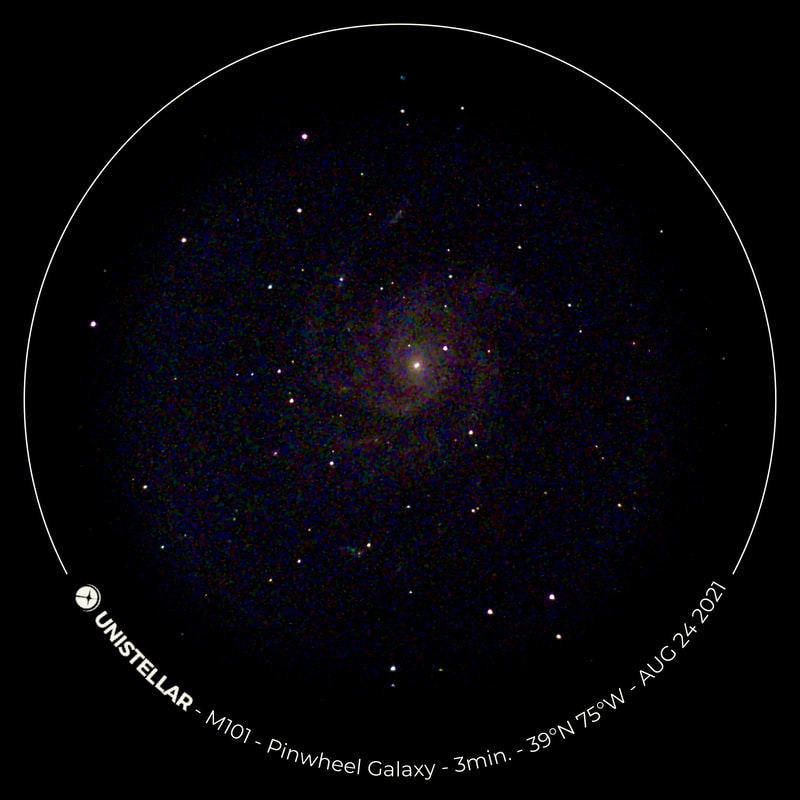

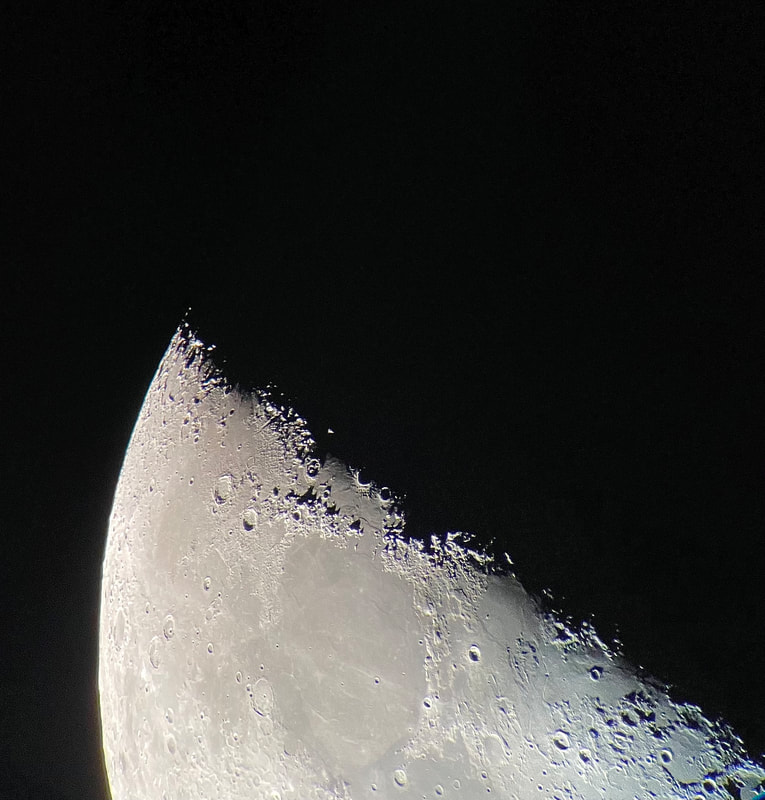

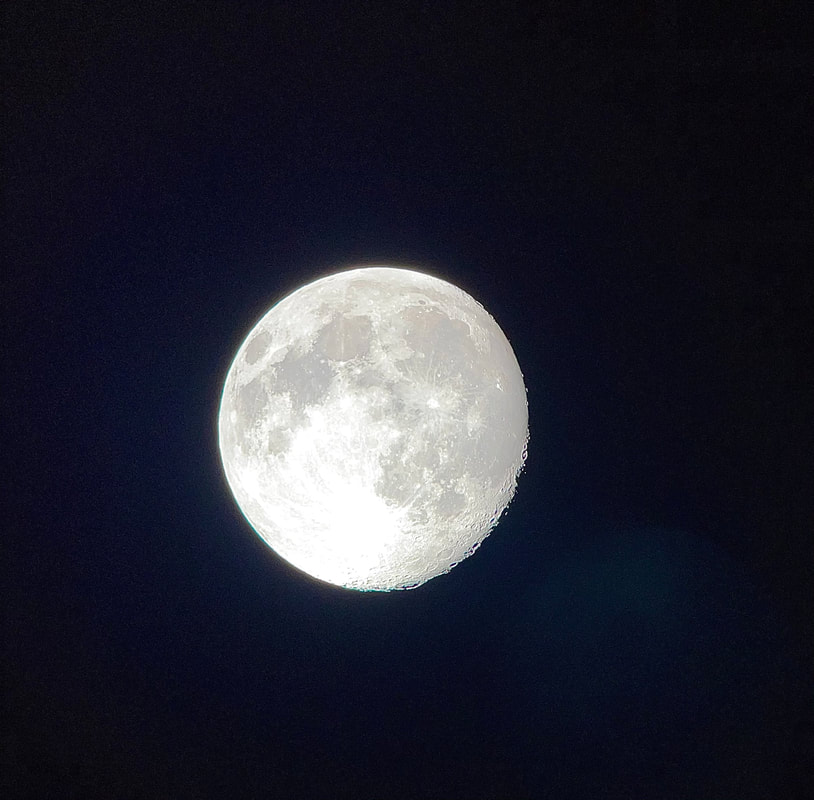

I packed up just as quickly as I set up, and then a pleasant walk home with my backpack. It is simply remarkable to see so much so easily. I've often seen the EVScope's hardware discussed and praised, yet what really stands out to me is the software. If only other mounts, carrying regular telescopes, were so easy to use. It seems that the cloudy, turbulent days of winter - in more ways than one - are finally coming to an end. In the wee hours of March 20th, the sky was clear, transparency was (supposed to be) high, and seeing was about average. Conditions, in other words, were about as good as we've had in months. I trotted out with my EVScope, intent on imaging some of the deep space wonders that are now prominent in the early modern sky. After a lightning-quick setup, as usual, I directed my attention to M51, the Whirlpool Galaxy, which is colliding with (and ripping apart) NGC 5195, a smaller galaxy. After a seven-minute exposure, the results impressed me - and for once I noticed that the image looked better when I peered through the eyepiece. Two other galaxies beckoned around the same constellation (Ursa Major, or the Big Dipper): Bode's Galaxy (M81) and the Pinwheel Galaxy (M101). Both are much trickier targets. Bode's bright core is easy to find, but its spiral arms are easily lost; the Pinwheel is big, but has generally low surface brightness. While transparency was supposed to be high, the sky was actually remarkably bright, and I noticed clear halos around street lamps. If anything conditions promised to be poor for both galaxies, and sure enough I wasn't pleased with the results. Here's a three-minute exposure of the Pinwheel Galaxy; you'll see it doesn't exactly impress. That's the thing with the EVScope, and something I haven't seen mentioned in any review: like all telescopes, it performs much better under a dark sky. While there's a lot of hype about how it will reveal deep space objects in the middle of the city, that promise holds up much better for objects that are already bright. Fainter objects can be lost in the glare of light pollution, just as they are in traditional optical telescopes. I'll try these galaxies again when conditions are better, but I don't expect radically different results. By the evening of the 20th conditions had improved dramatically. Both seeing and transparency were now good: a confluence we haven't had here in DC since November, maybe October. Although I was exhausted from waking up early on the previous night, I had to walk out with my Takahashi to catch the Moon while it was still quite high in the sky. As I've written, I've been a little disappointed since swapping my FC-100DC for the DZ, which is supposed to offer slightly better color correction. While I had only used it in nights of bad seeing, I was beginning to worry that it might have been knocked out of collimation in transport. After I set up on the night of the 20th and glanced at the Moon, those worries only grew: the image looks distressingly soft, and I started thinking about how to contact Takahashi. Yet after a few minutes the telescope cooled down, and then: wow. Suddenly the Moon snapped into crystal clear, razor-sharp focus, with absolutely zero false color anywhere - including along the lunar limb, where the slightest undulations and shadows were totally crisp. No matter which eyepiece I used, the detail was spectacular. What stood out the most? Probably the rilles; they seemed to be everywhere, and so delicate that they looked like veins on a living thing. After a little while I concluded that the view seemed best with my 6mm Delos at 133x. At that magnification I could still see the entire Moon, but I was close enough to make out truly breathtaking detail, in every conceivable shape and form. It truly felt as though I was looking out the window of a spaceship, approaching the Moon after a long journey from Earth. There are times when the atmosphere cooperates, and something spectacular is in the night sky, that it doesn't take long for me to have my fill; to feel as though I can't take in any more, because I just want to savor and remember what I've seen. So it was this night. After about 40 minutes, I packed up and walked home. So yes, the FC-100DZ is an extraordinary telescope. To me, it has a bit less false color than the DC and significantly less than the TV-85, although both of those telescopes really had very little, and that gives it a small edge in sharpness. The difference is subtle but noticeable - on nights of good seeing. Of course, those night don't come along very often, and I've found that on most clear nights the state of the atmosphere matters far more than slight improvements in instrumentation. The FC-100DZ's bigger improvement over the DC, as I've written, is probably its modest but meaningful mechanical upgrades. Still, owing fine refractors has made me a little obsessive about the details, and for me the move from a DC to a DZ appears to have been worth it. That's a relief! I've written it before, but wow: Washington, DC is such a feast or famine city for amateur astronomy. We've had bad seeing on just about every clear night (and there haven't been many) for around five months now. At last, this month, the clouds parted - but on night after night, the seeing remained poor at best. I took out the Takahashi FC-100DZ twice, and both times found the seeing well below average. Both times the Moon failed to impress as it otherwise might, and stars shimmered and danced in the eyepiece. Mars had long since set; I won't have another good look at the planet until 2022. At last, at 4:30 AM on Wednesday morning I stepped out with my EVScope and found the seeing to be . . . okay? It was windy near the ground, to my great frustration, but the stars scarcely twinkled and the internet confirmed it: seeing, it seemed, was about average. Of course that doesn't matter as much as transparency when you want to observe most deep space objects, but transparency was average, too. The sky, in other words, was about as good as it's gotten since autumn. It was a little cold, however, and muddy where I set up in the park. I hoped to test the EVscope on the Ring Nebula and the Hercules cluster: two objects I admired last year with my refractors. The scope aligned itself within seconds - why can't other mounts do this? - and I soon found it to be in perfect collimation. Moments later, it had found the Ring Nebula and I began a short exposure. As I wrote last year, under urban skies the Ring Nebula looks like a ghostly grey ring with a fine four-inch refractor - a ring you can just, just make out with direct vision. Using the APM 140 with averted vision, the ring was plainly obvious. In darker skies, with a four-inch Takahashi, the ring was equally obvious and appeared a little flattened. Every time I looked, there was a visceral thrill to seeing it, with just a couple lenses between my eye and the nebula. Yet through the eyepiece, the object itself was a subtle pleasure. The experience couldn't be more different with the EVScope. That thrill of seeing something with your own eyes is just about gone. Unlike others, I really don't like looking through the scope's eyepiece; it's like looking down a barrel, for one, and at the bottom of that barrel it's clear that you're seeing a screen. Maybe I've been spoiled by fine refractors and fine eyepieces, but it's a letdown. So I look at my phone, and for the most part I wait. The experience of observing - of learning how to see - is completely lost with the EVScope. Yet the thrill of seeing deep space objects otherwise barely visible from the city beginning to resemble their true selves is simply something you can't get with a traditional telescope under an urban sky. This time I really was floored when the nebula almost immediately turned green on my screen, and then when its perimeter began to seem orange, and then when its interior started to take on a greenish hue. The breeze pushed on the tube just enough to blur some of the stars, but what a wonder. Observing the Hercules cluster was a slightly different story. The cluster is always a highlight for me, not least because it's three times older than Earth - or because we beamed a message there from Arecibo, in 1974. With one of my refractors, it looks like a smudge at first from downtown DC, but after a while the stars come out, like diamond dust on a velvet background. It's subtle - exceptionally so with one of my smaller scopes - but magical nonetheless.

Again, the experience couldn't be more different with the EVScope. Hundreds of stars are easily visible, but of course they're slightly bloated; they lack that crushed gemstone beauty that you get with a fine refractor. Many of the stars are also clearly red, a testament to their age: again, things are visible through the EVScope that just aren't accessible with a regular telescope. Is the view more impressive? Maybe not to an experienced observer, but it's different, and that's a good thing. Some complain that the EVScope delivers the same experience you might get with a much cheaper (and more unwieldy) astrophotography setup. That's just not true. The EVScope is marvelously portable, and I can set it up in about one minute. It needs virtually no time to cool down. It's a joy to use and on most nights there's no fuss at all. In half an hour I can pack up - this takes another minute - having observed at least three deep space wonders as I otherwise never could. The key point is that the EVScope delivers a fundamentally different experience than you'd get with either a traditional telescope or an astrophotography setup - and again, I view that as a very good thing. On November 16th, the sky was clear and, after a glorious sunset, atmospheric seeing promised to be mediocre but transparency was predicted to be superb. With no Moon in the sky, conditions were right to take the EVScope for another spin. I've now (separately) purchased the backpack that's sold with the EVScope; my rolling case, I suspect, my knock the telescope out of alignment. When I set it up this time, collimation was just about perfect. I made a couple tiny tweaks - again, this took seconds - and then rapidly achieved fine focus with the built-in Bahtinov mask. It was cold and I was exhausted, so I figured I would only take two ten-minute exposures of the Andromeda and Triangulum galaxies. Moments after the telescope slewed to Andromeda, I heard some rustling in the distance and noticed a dim orange glow, appearing and disappearing. Then the sounds of muttering wafted over on the breeze. It seemed I was sharing my park - and I had the disquieting feeling that I was being observed. After about eight minutes or so, I thought a third shadow joined the two in the distance, and then the rustling got closer. The conversation, it seemed, was definitely in Russian. Suddenly a flashlight turned on; there were three people, and they were walking directly towards me. I greeted them: "Hello? Hi!". At that, one of them exclaimed "oh my God!", and then all three of them darted to the side, behind a bush, and disappeared. The sounds receded into the distance. That was unsettling. Fortunately, after ten minutes the Andromeda exposure turned out nicely, considering the light pollution. Collimation and fine alignment really makes for much tighter stars and far better images, though I imagine things would be better still in superior seeing (and, of course, under a darker sky). Now it was on to Triangulum. It wasn't long ago that I managed to spot the galaxy with the FC-100DC, under darker skies some distance from DC. I noticed only a slight brightening of the sky, with averted vision, in what I could just perceive - or imagine - to be a spiral pattern. Clearly observing the galaxy now, from downtown, is a particular thrill. I don't know why, but Triangulum in particular has always captured my imagination. Maybe it's because it gets so little attention compared to the two giants of our Local Group of galaxies, or maybe because it's a face-on galaxy with distinctly knotted spiral arms . . . I'm not sure why, exactly. In any case, I find that the EVScope does a particularly good job on this galaxy (see above). And again, during the exposure I was in for a shock. With a loud thump and a lot of growing, a rabbit suddenly rushed right by the telescope, a fox in hot pursuit. The fox stopped short of my location with a snarl, then scampered - its little legs a blur - over a hill and behind a bush. Both fox and rabbit were no more than six feet from me. I couldn't wait to tell my four-year-old daughter in the morning. Anyway, after a few more minutes the Triangulum exposure was done to my satisfaction. I packed up the telescope, warmed my chilled fingers, and walked home. Suffice it to say, I've really started to enjoy the EVScope. A few days after my strange night with the EVScope, an ad appeared on AstroMart that forced me into hours of tortured thought (usually while attempting to get my one-year-old to sleep). Here was a Takahashi FC-100DZ, used only once and in pristine condition. As I've mentioned before, this year I've been tempted to swap my 100DC for a DZ. The DZ has better color correction and its optics might be marginally sharper, on average, though both improvements may be difficult to detect visually (I read many opinions, and they seem to differ). You can read a great breakdown of the relative merits of the four current FC-100 models here. I've resisted the urge to swap the DC for the DZ because, first, the hassle and expense seemed daunting, and second, the DC's weight is supposed to be lighter. The difference in weight, I concluded, outweighed (sorry) the marginal difference in optical quality. Yet the four-inch refractor is my most used telescope, and now I couldn't resist the urge to upgrade to maybe the finest refractor of this size ever made. So, I bought the DZ and sold my DC (along with some other stuff to make up the cost). I have to say, the comparison between DC and DZ surprised me in a few ways that aren't covered elsewhere. First and for my purposes most importantly, the weight difference between the two telescopes is scarcely noticeable. In the above pictures, you can see the DZ in a configuration for short-range, daytime viewing. However, to reach focus for astronomical viewing you must detach one of the couplings, and that makes the DZ noticeably lighter. It is then also more compact than the DZ when the sliding dew shield is tucked over the optical tube. Second, the most important couplings of the DZ do not screw apart but rather use thumbscrews and compression rings. You can also use that system to attach a diagonal, and I can't tell you what a difference it makes. I actually detest the Takahashi fetish for stacking screwable couplings in the visual back. The couplings, I've found, tend to stick together, and they're not wide enough to grip easily. It's easy to damage them (cosmetically) by applying too much pressure (I did as much to one of the DC's couplings). The new system brings the DZ in line with most other fine refractors, and it is just such a relief. Third, to balance the telescope - using just about any eyepiece - the clamshell tube holder must sit farther from the visual back than it does with the DC. This may seem like a very minor detail, but it provides more room for a red dot finder (RDF) just in front of the visual back. My Rigel QuikFinder RDF is now in a more comfortable position, and it's those little details that can make a real difference in the field. Fourth, the focuser is just a bit nice. Its knobs are metal - not plastic, as in the DC - and the feel is a bit smoother (though I did need to adjust the tension knob for my big Delos eyepieces). I sold Takahashi's two-speed focuser upgrade with the DC, and although I will no doubt miss the fine focus on the DZ, I didn't like how the two-speed add-on left some daylight around the gear housing. On the DZ, I'll stick with the stock focuser. That focuser, by the way, allows me to reach focus with all my eyepieces - something that was just out of reach for the DC. Finally, although the sliding dew shield is very smooth and easy to use, its tightening screw does leave a subtle mark on the optical tube that is noticeable when the dew shied is deployed. I wonder if the previous owner tightened the screw a bit too much, but I doubt it; I think this is just a natural consequence of the technology. It only matters if you're obsessive about the condition of your equipment - but Takahashi telescopes are so beautiful that they tend to bring out that obsession. Last night, and against my better judgement, I took out the DZ for the first time. I say "against my better judgement" because transparency was mediocre and seeing was poor. It's a recipe for disappointment to take out a new telescope in such conditions. I couldn't resist, but I did set up near the cathedral, closer to my house so I could hurry back if observing disappointed.

And did it? Well, a look at Mars did clearly reveal that the atmosphere would not be my friend tonight. And yet, I could plainly make out no fewer than three large dark albedo markings, along with that brilliant south polar icecap. Turning elsewhere, Rigel A and B were laughably easy to split in the poor seeing, and Orion was beautiful even before it emerged from the light pollution near the horizon. So could I make out an optical difference between the DC and DZ? Not after one night of poor seeing. Mars did seem a bit yellower than it does through the DC, and certainly I could detect absolutely no hint of false color in or out of focus. I'm excited to study the Moon, for example, on a really good night. Yet I don't expect a large or even a plainly noticeable difference. I bought the DZ primarily so I could be absolutely sure that the optical quality of my most-used telescope would never hold back my observations - and so that I would never wonder what something would look like with a slightly better telescope of the same design. It's a tiny thing, but after a while tiny things start to matter a whole lot in amateur astronomy. It was a cold, damp night when I stepped out with the EVscope and found a relatively mud-free corner to set up in my park. I decided to try my hand at collimating the telescope to see if that might tighten the stars in my pictures, and I hoped to decide, once and for all, whether to keep the telescope before my refund period ran out. To my surprise, the telescope was badly out of focus when I turned it on - so out of focus that its auto-alignment failed. Fortunately, it comes with a bahtinov mask cleverly built into the dew shield. Achieving rough focus, and then fine focus with the mask, takes a matter of seconds. With that done, the telescope immediately found alignment, and I got it to slew to Bellatrix, a fairly bright star in Orion. Now I turned the focuser knob until a dark cross appeared in front of the suddenly bloated star: the spider vanes holding up what would be a secondary mirror in most reflectors (but is a sensor in the EVScope). The cross was badly askew, which means that the telescope was poorly collimated. It took all of 30 seconds or so to fix the problem, and even less time to achieve fine focus again. And then, voila: the stars were more closely to dots - rather than smeared blobs - and the resolution of the telescope suddenly seemed higher. Funny how that works. I tried my hand at imaging a few objects: the Orion Nebula, of course, and the Flame Nebula, Bode's Galaxy, and the little galaxy NGC 1637. The latter was a bust: it's very small, and lost in the glow of light pollution to the south. An unavoidable problem for me is that the EVScope amplifies both the light of deep space objects and the light pollution in our DC skies. It's not a problem for brilliant objects like the Orion Nebula or the Andromeda Galaxy, but dim, diffuse objects are another story. I also didn't take exposures longer than five minutes. It's one thing to gawk at the Moon or Mars for that long - or much longer - but another thing to sit silently in the cold, waiting. But was it ever cool to see the spiral arms of Bode's Galaxy, slowly brightening on my screen as the minutes and seconds ticked by. Here were photons 12 million years old, from a galaxy nearly the size of our own, somehow visible in an urban sky. The view was quite sharp, I thought, and the telescope performed perfectly, immediately slewing to whatever I asked it to find.

Do I prefer my optical telescopes? Yes, for most objects I do, but it's simply true that the EVScope shows me hundreds of nebulae and galaxies that I never imagined seeing from the city, and reveals glorious detail in wonders I thought I already knew well. It's a keeper. Now if only I could get a lightweight, go-to mount for my refractors . . . . We've enjoyed maybe the best stretch of clear nights with good seeing that I've experienced since moving to Washington, DC, and I was out nearly every night with a telescope in hand. Between work, childcare, and observing, I had no chance to update this blog - but now it's raining, and I have an hour (but just an hour) to relax. Roughly two weeks ago, I spotted a Takahashi FS-102 for sale on Astromart. Amateur astronomers will know that this is a four-inch refractor with a well-earned reputation for exceptional optics. It's been replaced by the Takahashi FC-100 series, and I already own a telescope in that line. But the FS-102, while much bulkier than my 100DC, does better at longer wavelengths. And in Mars-watching season, that's what I convinced myself I needed. Although the FS-102 was supposedly in pristine condition, when it arrived I was dismayed to discover that the lens cell was loose and the tube was covered - I mean covered - with scratches. Luckily, the owner was mortified when I informed him, and I received a (nearly) full refund. I now had some cash to spare, and at just that moment a new copy of Sky and Telescope arrived. A favorable review of the EVScope convinced me to give that telescope another chance (see a previous entry for my first impressions). Maybe the buggy version I owned before had unfairly soured me on the product? It did, after all, offer me a chance to observe nebulae and galaxies I would otherwise never have a chance to see from the city . . . . After it arrived, I bundled the telescope into a suitcase and rolled it along to my nearby park. After I turned it on, it just about instantly figured out where it was and slewed (quietly) to any object in the sky, like magic. Clearly, I'd been sold a glitchy version the first time around. This was more like it! And when I tapped on "enhanced vision" (I describe the technology in a previous entry), the effect was really satisfying. After a couple minutes gathering light on the Andromeda Galaxy, for example, dust lanes I'd previously spotted only with averted vision clearly snapped into focus. So, how good are the views? Well: although I managed to achieve fine focus, I think I'll need to collimate the telescope when I'm next out. Stars are not exactly pinpoints, as these images attest, and that's also caused by a tendency of the telescope to move too much while it's gathering and stacking images. There's more noise in the pictures than I'd prefer, and after getting used to my wonderful TeleVue eyepieces, the view through the EVScope's "eyepiece" is really cramped. It's like looking through a tunnel. More importantly: no, seeing an image through a grainy screen is just not at all the same as seeing it through an optical eyepiece. An optical telescope feels like an extension of the eye; not so the digital EVScope. But damn, it's cool to see galaxies shimmer into view on my iPhone screen. It's simply true that I can see things now that I never would have imagined seeing before, and isn't that what this is all about? I mean, the Triangulum Galaxy from an urban sky . . . are you kidding me? I'm still learning how to use this technology, and pictures I've seen online tell me there's plenty of room for improvement. Still, I've noticed that the images look much more spectacular in the app, while I'm in the field, than they do after I get home. Certainly they pale in comparison to even half-decent astrophotographs made with dedicated gear. Now does the technology always work seamlessly. Just a couple nights ago, I had to restart the telescope and reinstall the software before I could get the enhanced vision mode to work, and by then I'd already shivered outside for about 30 minutes. Some objects also look immeasurably better through my optical telescopes. The EVScope is just about useless for lunar and planetary views, and stars look like ugly blobs compared to the beautiful diamonds they resemble through my refractor. Yet what the EVScope does so well is find that sweet spot between visual observation and astrophotography, and it does so in an integrated package that's usually a pleasure to use. No, I never had the thrill of seeing something with my own eyes - the thrill I've described often in these pages - but I certainly did get a deep sense of pleasure when I glimpsed the Whirlpool Galaxy from the city. One virtue of the EVScope is its weight. If I stuff the EVScope into the suitcase I used for the APM - which, admittedly, does seem to mess with its collimation - then I can easily sling my Takahashi 60Q over my shoulder (and wedge its tripod in the suitcase). I've now used the 60Q twice, including once in the early morning, with the EVScope gathering Orion's light. I have to say: I was more than a little stunned by its quality. To my astonishment, the Moon through the 60Q really didn't look any dimmer than it does through the TV 85, and details were equally sharp. Here are three images I took of the Moon over the last week, with the 60Q, the FC-100DC, and the APM 140. A reminder: the 60Q has an aperture of about 2.5 inches; the 100DC of 4 inches, and the APM of 5.5 inches (these are big differences for refractors). The optical quality of each telescope is roughly similar, though I'd say the APM shows the most false color, and the 60Q the least. That's the 60Q on the left, and the APM on the right. The comparison isn't quite fair; seeing and transparency differed on each night - it was average when I used the APM, and decidedly better than average when I used the 60Q and 100DC - and while the smaller telescopes had fully cooled down when I took these images, the APM in my judgement had not. Still, it amazes me how slight the differences are. I have a new phone, by the way, with a much better camera, and I think it shows. These pictures were taken after the APM had fully acclimated, and I think it's fair to say that now the aperture difference is more easily visible. There's a deeper and more richly textured quality to these images than there is to the 60Q closeup above. Yet it always takes me aback to realize that, when telescopes are of similar quality, differences from night to night on bright objects - the Moon especially - owe more to atmospheric conditions than anything else, including aperture. It's different for dimmer objects. I can usually see at least five stars in the Trapezium using the APM, for example, but I've rarely if ever confidently spotted a fifth with any other refractor. Mars was full of detail when I observed it with the APM - wow that south polar cap looks bright and sharply defined right now - but I found that it, and every other bright object, was surrounded by a bright halo that night. This seems to be a common and very annoying optical effect in the skies of Washington, DC. On two nights with the 100DC, however, I had no such problem. Dark albedo markings were wonderfully detailed, and I spent easily an hour both nights just enjoying the view. It's a little sad to think that every night brings us a little farther from the red planet, but the view should dazzle for months to come. One last note. My first night out with the 100DC over these past two weeks was November 3rd. I suddenly resolved to stop doom scrolling and instead do something that distracted me. But what a sinking feeling I felt, walking bewildered to the field, with panicked screams - yes, screams - echoing around me. I walked out on the 4th, too, and the mood was lighter. Then, on the 7th, while playing with my kids in the very spot I usually set up my telescopes, came the good news: the networks had called it for Biden. I'll never forget the scenes of spontaneous joy on the streets: the bells ringing, cars honking, crowds cheering. We may be in for some very dark months this winter, but that was a moment I'll long remember. My greatest weakness in this hobby - and maybe in life - is that I'm never sufficiently content with what I have. When I realized that my big refractor - the APM 140 - was just about as portable as my smaller and substantially less capable Vixen 115 ED115S, I started imagining what I could get by selling that telescope. Eventually I discovered the Unistellar EVScope, a remarkable little device that uses a sophisticated sensor to amplify the feeble light of galaxies, nebulae, and globular clusters. The telescope uses a technique familiar to astrophotographers - stacking images on top of each other - to provide detailed, colorful views of these objects. In theory, I reasoned, the EVScope could finally allow me to explore deep space from the city, something I've long dreamed of. The EVScope has received rave reviews from popular outlets, mixed reviews from astrophotographers, and a great deal of skepticism from seasoned observers at such websites as CloudyNights. To me, its potential was too great to ignore. I sold the Vixen and took the plunge. So, was it worth it? In a word: no. Yet I'm not disappointed, as I had to try - and I'm convinced that this has more to do with my unique expectations and restrictions than anything else.

First, the good: this is a beautifully-built product, compared to other examples of fine consumer electronics. Yes, the mechanical beauty and precision of one of my refractors, for example, makes the EVScope look like a toy. Yet it has the kind of sleek, effortless style of the Apple laptop I'm using to type this blog. Its tripod is lightweight but absolutely sturdy, while its motor slews quietly and smoothly to its targets. The app you use on your phone to control the device is wonderfully easy to use, and the instructions that come with the telescope are really well done. The whole setup provides a masterclass in accessible ease of use. Now for the bad. I spent three, maybe four hours with the EVScope before selling it. In my first session, on our rooftop, a gaggle of interested residents kept wandering over while I attempted to set up the telescope. What was I looking at? They wondered. Nothing yet, I replied, it was my first time using the telescope. Oh you'll never see anything in the city, they assured me. Eventually it got to be too much - none of my neighbors decided to wear masks - so it was back downstairs for me. I noticed that the telescope failed to achieve alignment on the rooftop, but I blamed that on the nearby lights. During the next two sessions, I walked to the nearby park. Again the telescope struggled to achieve alignment, and even when it claimed to be aligned it typically did not maneuver accurately to the right object. A back and forth with tech support (who took four days to get back to me after one query) reassured me that any problems could be solved. Yet did I have the time or energy to solve them? The reason I ultimately decided I did not has a lot to do with the telescope's "enhanced vision" feature - the feature that starts stacking images. I was impressed by the many stars that gradually winked into view when I turned it on, but somehow profoundly disappointed by the experience of seeing them. It reminded me of buying a microscope, not long ago, with an LCD screen. Adding that level of separation between reality and the eye, for me, deprives the observing experience of its most essential characteristic: actually, really, seeing what is otherwise hidden. As soon as there's a screen - and there's a screen with the EVScope even when using its eyepiece - the experience is ruined, the effect is gone, and I might as well be home scrolling through Hubble Space Telescope images. Not everyone would feel that way, but I suspect that many amateur astronomers will. It's why we spend far too much time and money to admire the faintest smudges and hazes and pinpoint pricks of light that, our brains remind us, have almost unimaginable significance. The EVScope is tailor-made for those who don't feel that thrill. As I was struggling to align the telescope, I eventually pointed it at the Moon. Here was a third disappointment: the Moon, through the telescope, was incredibly unimpressive. My aging cellphone, held up to my C90, provides a far superior view. I realized that no matter what, I would never used the EVScope with any bright Solar System object in the sky, and since lunar and planetary viewing at my primary interests, that really knocked the wind out of my sails. And this too: while I sat hunched over the EVScope in the park, someone walked close to me with a flashlight, shone it at me, and then silently walked away. Was it the sound of the motor that had attracted them? Or the red light on the telescope's base? Either way, it echoed my experience on the rooftop - and it reminded me why I don't like the silence of simpler devices while observing in the city. That, and wow do I have hate wrestling with electronics in the few hours I have to observe. I tried to suppress the thought that those three of four hours of frustration could have been truly wonderful had I brought my other telescopes to the park. So it was that the EVScope left my house this morning. I hope that the buyer likes it more than I did; certainly, there's plenty to like. Yet for my needs, with limited time in the city, it just doesn't cut it. I lost a few hundred dollars in the transaction - that always hurts - but fortunately found the C9.25 on sale for a few hundred dollars off. I bought that telescope with a couple upgrades, and now will wait until it arrives in a month or so. If there's one telescope I've regretted selling, it's the orange tube C8 I had earlier this year. As much as my experience with the Edge HD warned me about Schmidt-Cassegrains, the orange tube restored my faith. So, here's hoping that the 9.25 provides a level of planetary performance that even the APM 140 can't quite match. I suppose that, for now, I need to accept that some corners of deep space are simply off limits for me in the city. |

Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed