|

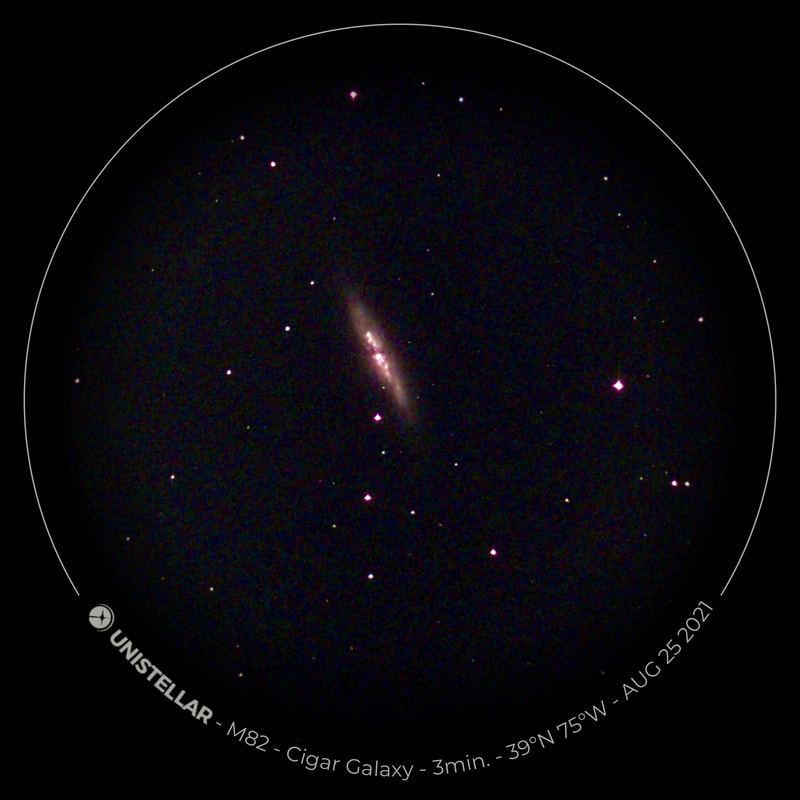

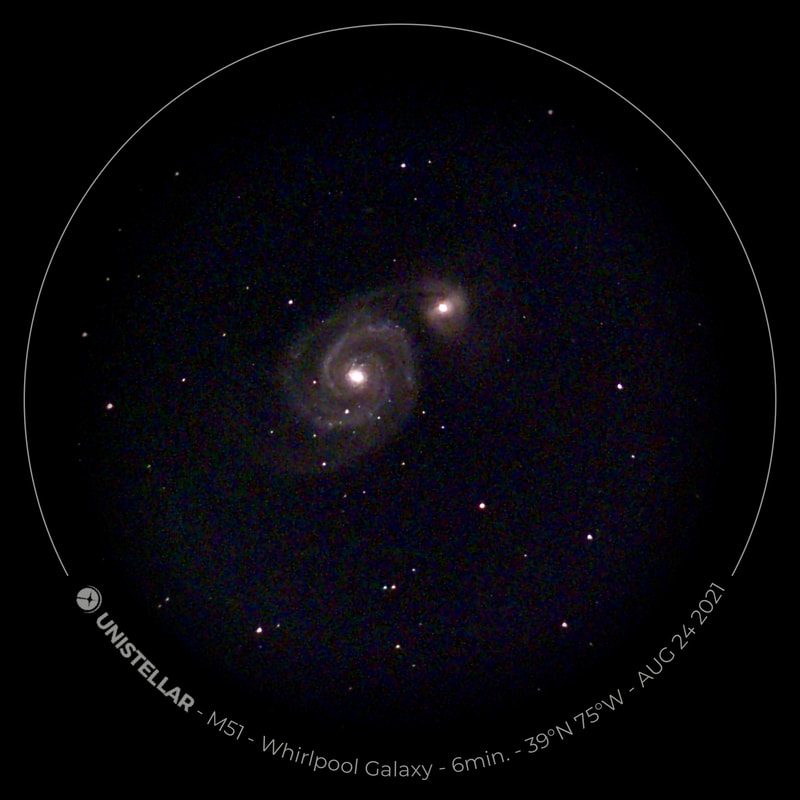

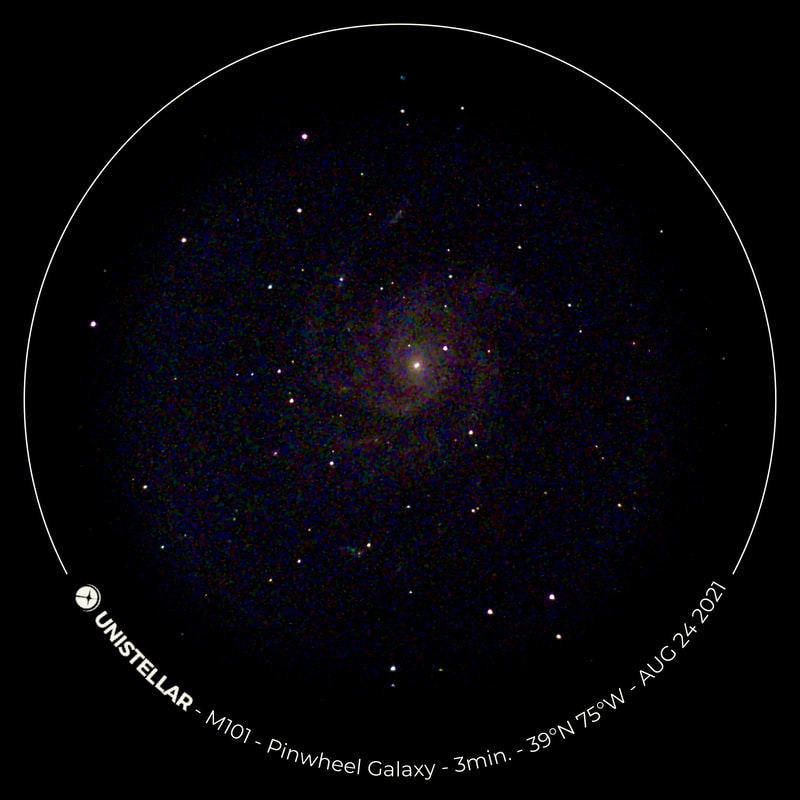

Recently, I've been on a mission to optimize my grab-and-go setup. Slowly but surely, parks that offered dark corners for a telescope have been saturated with bright lights: the kind that needlessly waste energy, confuse nocturnal animals, and pollute the night sky. I have to walk further than I have before, or settle for less than ideal observing conditions. To that end, setups that used to feel perfectly mobile now are discouragingly cumbersome to use. I admit I was tempted to swap my FC-100DZ for a lighter telescope, such as the FC-100DC I used to have and love. Then I had an epiphany - one I should have had long ago. With its diagonal removed and dew shield retracted, the DZ is just over two feet long. Couldn't I find a padded bag that long? If so, the DZ would be as easy to transport as my dearly departed TV 85, while offering considerably better performance. I found the bag - for just $23! - and wow: what a difference. It's strange but true: the DZ is as transportable as much smaller telescopes, but offers truly stunning views of everything that shines through light-polluted skies. The other night, I pointed it at Saturn, which is just now reaching opposition (its closest annual approach to Earth). The view was spellbinding, with glimpses of detail in the planet's clouds that were among the finest I've seen. On the other hand, DC's summer mosquitoes did not give me a moment's rest, and I was grateful that my little setup takes just a few minutes to disassemble. Then, last weekend, it was off for what has become an annual trip to the beach near Lewes, Delaware. I brought my EVScope 2, eagerly anticipating darker skies. Unfortunately, I soon found that atmospheric transparency was lower near the beach than it has been in years past - owing, once again, to that wildfire smoke. Worse, my recent experience with a truly pristine sky in Manitoba left me unimpressed with the view in Delaware. Sure, the Milky Way was barely, and I mean just barely, visible after fifteen minutes outside in the dark. But there was simply no comparison. I occasionally fantasize about selling my EVScope in exchange for a more capable astrophotography setup. The three (!) clear nights I experienced in Lewes reminded me why I have that fantasy - and why I haven't acted on it yet. First, the telescope needed collimation. If you've read any reviews of the EVScope, you'll know that some complain about the need to collimate such an expensive gizmo. Let me assure you that it's much easier than collimating an SCT, for example. Even when the telescope is badly misaligned - as it was for me in Lewes - the entire process takes a few minutes at most. The real problem is that Unistellar's instructions include a glaring error. To collimate the telescope, it should not be pointed at a particularly bright star - I tried Antares - because the star's brilliance will not allow you to see the secondary mirror when out of focus. I suppose it's a minor detail, but this little mistake can create a lot of frustration. Usually, it takes just moments to align the EVScope and get it ready to slew to any object you can imagine. Usually. On one night in Lewes, I had to turn off the telescope a couple times before it aligned itself. On two other nights, it did not precisely center objects after finding them - so that, at the telescope's highest magnifications, objects were simply offscreen. On a third night, everything worked seamlessly. I carefully leveled the telescope, collimated it, and waited over thirty minutes for it to acclimate. That may not sound arduous to veteran amateur astronomers - but it's hardly ideal for a grab-and-go setup. When the telescope is aligned, it tracks objects seamlessly. The trouble is that its altazimuth mount cannot perfectly track stars on long exposures. This isn't visible while peering into the eyepiece, but it does show up clearly in astrophotographs taken with the telescope. Since most people will use the telescope by staring at their phones or tablets - in fact, some Unistellar models don't even have eyepieces - this is a serious limitation. Even this six-minute exposure of the Eagle Nebula has distorted stars. Stars are also distorted - even through the eyepiece - because stars shimmer in all but the steadiest atmospheric conditions. When using a traditional telescope - especially a refractor - you may see a roving, flickering pinpoint. Yet the EVScope takes exposures to provide its bright views of deep space objects, and in these exposures the undulating pinpoints that are stars in mediocre seeing all congeal into blurry blobs. For a refractor aficionado like myself, the effect is deeply unsatisfying. To me, it really does not feel like you are actually peering into space when you use an EVScope. Occasionally I wonder: what am I getting here that I could not obtain by finding images on the internet? Have a look at this shot of the Wild Duck Cluster, for example. The problem is compounded by the reality that Unistellar's software cannot quite compensate for the effects of light pollution. Overall, it does a remarkable job - I'm still amazed that I can admire the Triangulum Galaxy from downtown DC, for example - but there's still a good deal of noise even under a Bortle 4 or 4.5 sky (as in Lewes). Have a look at this 24-minute exposure of the Pinwheel Galaxy, and notice the noise. Another inconvenient truth is that, even with the galactic core above the horizon in the summer, there just aren't that many objects that truly impress when viewed with the EVScope. You have to remember that although the EVScope allows you to view galaxies and nebulae that are far beyond the reach of a comparably-sized traditional telescope, it is also incapable of providing satisfactory views of many objects that such a telescope would reveal. Open clusters, double stars, the Moon, and the planets: everything that impresses when seen through a telescope like the Takahashi FC-100DZ is underwhelming at best when viewed with the EVScope. In practice, dozens of objects in the EVScope's catalogue look like this, and hundreds are far less impressive. The EVScope also seems to have a weak wifi signal. Walk twenty feet away, and you're likely to lose it. You can forget about sitting indoors while operating the telescope. That's too bad, because mosquitoes really can make it hard to stay outside in our muggy summers. In other places, winters are just too cold for comfortable observing. Wouldn't it be easy for Unistellar to include some way of amplifying the wifi signal on its $5,000 device? So yes, I was getting a little annoyed in Lewes. I kept imagining what my TEC 140 might reveal; not nebulae in a distant galaxy, sure, but pinpoint stars on a velvety black background, and spectacular planetary views. This is the best that the EVScope can do on Jupiter, even after a recent software update that dramatically improves planetary performance. I admit: I could go on. Suffice it to say that my nights in Lewes reminded me that, if you buy an EVScope, you really should go for the EVScope 2. This is because the eyepiece is really a lot better than some reviews suggest. Somehow, images of nebulae and galaxies are much brighter and sharper through the eyepiece than they appear to be when viewed on a phone or tablet. The distortions I complained about above - those blurred stars, in particular - are also minimized when viewed through the eyepiece, likely because the small scale of the image mitigates them. As a result, I am consistently impressed by the nebulae and galaxies I see through the eyepiece; so impressed that I take an image that then disappoints. Just before I took the image of the Pinwheel Galaxy that you've already seen, I invited my wife and our friend outside to have a look. Both are astronomy novices, to put it mildly. Both seemed skeptical that they'd see much. Yet when both craned over the EVScope eyepiece, they gasped. They could not believe that they had seen a whole galaxy across 20 million years in time and space. They kept saying how cool it was. "It's almost like one of those picture slide viewers," my friend eventually said. Indeed. You see so much more - and so much less - than you would with an ordinary telescope. That is why I think I'll keep the EVScope . . . for now. Here are some extra images, showing medium-length exposures of some of the best-known sights in the summer sky.

0 Comments

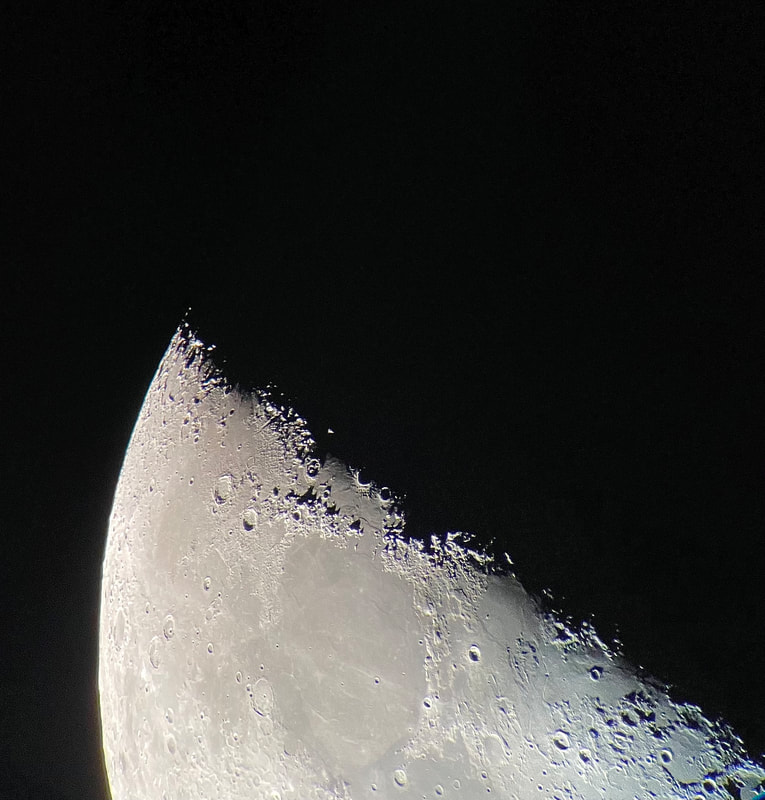

To put it mildly, it's been a dreadful summer for astronomy in Washington, DC. The primary culprit is wildfire smoke, which seems to waft into the city with every clear night. As a professor whose primary preoccupation is climate change - and as a dad - the smoke fills me with dread. It is alarming for any number of reasons, but it has extra significance for those enamored with the night sky. The atmosphere is likely to be less transparent on a warming planet, owing either to wildfire smoke or aerosols intentionally seeded into the stratosphere. That second possibility is known as solar geoengineering. It's cheap (compared to the cost of global warming), it's likely to be effective (despite a litany of troubling side effects), and I'm increasingly convinced it will happen within twenty years. In fact, this summer the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy released a primer that more or less accurately describes where the science of geoengineering currently stands. If plans currently on the drawing board someday take off, astronomy as a science and hobby will change - quite possibly for the rest of our lives. In all likelihood, planetary observation won't change much, and Electronically-Assisted Astronomy will still reveal deep space marvels. Yet my suspicion is that traditional telescopes - including big Dobsonian reflectors - will be far less effective for observations of diffuse objects far from our Solar System, such as nebulae or galaxies. You've been warned! Anyway, I did manage to see one spectacular sight in DC this summer. In May - just before the worst of the smoke surged south - a supernova exploded in the Pinwheel Galaxy. I hauled my EVScope to a nearby field and had a look. The above picture is all I managed to capture, but the view through the eyepiece was far more impressive. I still can't believe I managed to see an exploding star - and, in all likelihood, the formation of a black hole - 21 million light years from Earth. More recently, I travelled with my family to Winnipeg. Despite its closer proximity to the many wildfires burning through British Columbia, the city has been less affected by wildfire smoke than Washington, DC. The sky is not quite free of smoke, but it's a good deal more transparent than it's been further south. This was my first trip to the city since the pandemic, and I'd nearly forgotten that I cobbled together a fairly impressive little observing setup here. Four years ago, I had a Twilight I mount delivered to my in-laws. I also purchased a C6 shortly after I was last here, and it was still in the box when I arrived this time. I unpacked it with some trepidation - the last C6 I purchased was damaged upon arrival - but not to worry: to my relief, the little telescope was in perfect condition. With everything assembled, I was struck by how well the C6 fits on the Twilight mount. I don't think it could handle a C8, but a C6 is just about perfect. It's quite stable, convenient to look through, and remarkably easy to move. In fact, I can lift mount, tripod, telescope, diagonal, and eyepiece - everything - above my head with ease. I swapped out the standard Celestron diagonal - a child's toy - with a TeleVue Everbrite, and used a Baader Mark IV Zoom for an eyepiece. The field of view, I must admit, is a little too narrow, but then a Schmidt–Cassegrain really isn't a wide-field instrument. I was gifted one clear night after another since arriving here, and used the first two nights to admire the Moon. This far north, it doesn't rise far above the horizon right now, and it is tinted a beautiful pinkish-gold by the diffuse smoke in the upper atmosphere. Seeing was mediocre at best, but the telescope turned out to be well collimated, and the view was quite striking. As the above image attests, the Moon was not as sharp as it would be through one of my refractors. Even in mediocre atmospheric conditions that prevailed here, the Takahashi, I'm sure, could have shown me more. But when you consider the relatively low cost of a C6 - albeit much higher than it was pre-pandemic - the telescope is a remarkable performer. I was particularly impressed by how cleanly it snapped into focus; in fact, finding focus seemed a little easier with the C6 than it is with my refractors. I was genuinely delighted to discover that Saturn now rises high enough above the horizon to observe at around midnight. The planets might have drawn me outdoors this summer despite the wildfire smoke, but often they had set before I could step outside. Well - Saturn, at least, is back.

The C6 offered a really satisfying view of the planet, with the Cassini Division clearly visible at 75x. I'm not sure my Takahashi would have done that much better, given the seeing. In a cooperative atmosphere, I have no doubt that the refractor would outpace the Schmidt–Cassegrain; there is a delightful crispness to its views that the stubbier telescope can't quite match. And of course, it never needs to collimate or acclimate (for long). Nevertheless, I was stunned when, later, the C6 showed me Arcturus as a perfect orange point: something I had not expected from a Schmidt–Cassegrain. For those less obsessed than I am with getting the absolute best views that a (modest) aperture can provide, I suspect it would be impossible to justify the extra cost of a 4" apochromatic refractor over a C6. Well done, Celestron! Anyway, I had a truly wonderful half hour on the porch, the crickets chirping nearby as I admired the ethereal beauty of Saturn's rings. I was struck by how much their tilt relative to us has changed over the past year, and I fear that they will - briefly - disappear from view entirely in the months to come. It will be fleeting. Soon enough, the rings will return, and the planet will regain its grandeur. For me, one of the joys of astronomy lies in the knowledge that however badly we muck up our planet, countless wonders glitter beyond our reach. With or without us, it's a beautiful universe. It was Father's Day yesterday, and I had sanction to wake up late. When I found out the night would be clear, I was full of anticipation - until I realized that seeing was forecast to be about as bad as I can remember. I stepped out after sundown, however, and found the stars unusually visible in the night sky. Sure enough, transparency was high above average - which made sense, as the night as unusually crisp for a DC summer. Out I stepped at around 1:30 AM, burdened like a Tolkien dwarf with the EVScope II on my back, and a tripod in hand. This time I walked to a nearby school's soccer pitch, which not only affords an impressive view of the whole sky but is also (strangely) bereft of street lights. I set up in a few seconds, then targeted the heart of the Milky Way as it rose well above the southeastern horizon. The light pollution is very bad in that direction - it's right above the National Mall - but still, I had high hopes. I've largely praised the EVScope in these pages, and rightfully so. In a matter of moments the Omega Nebula emerged from the background light pollution, and wow that is an impressive effect. After a five-minute exposure, I moved on to the Lagoon Nebula, with much the same results. I now slewed to the Owl Nebula, but this time the view underwhelmed - even after five minutes - and it's not surprising: at around tenth magnitude, it's a challenge for the EVScope in light-polluted skies. As the chill began to set in, I finished up with the Sunflower Galaxy: a faint spiral roughly the size of the Milky Way, 27 million light years distant. It was a subtle view after six minutes or so, but still recognizable. I had profoundly mixed feelings as I walked home. On the one hand, it continues to amaze me that the EVScope brings nebulae and galaxies within my reach, from downtown DC. On the other - and this can't be stressed enough - using the telescope is not comparable to traditional observing. With a regular telescope, the bulk of your time is spent straining at the eyepiece. You train yourself to see like observers have for centuries - using averted vision, for example - and there's an art to it that you can improve over time. When you're not observing the obviously spectacular - Saturn or the Moon, for example - then what's visible through the eyepiece can be absurdly subtle. The average person would never recognize, let alone appreciate, what you can just barely glimpse. What makes it special is the sensation of seeing with your own eyes what can otherwise be admired only in enhanced pictures. You are truly experiencing the universe, albeit only as well as imperfect optics and a turbulent atmosphere will permit on any given night. With the EVScope, by contrast, you navigate an app on your phone. You stare at a screen as the telescope effortlessly targets and then observes your chosen object for you. Slowly, a picture emerges of the object you've selected. It's a little like a picture you can Google - something taken by Hubble, for example - except way worse. As the picture slowly brightens, you wait. You scroll through other stuff on your phone, perhaps, or you sit there thinking. One thing is for sure: most of the time, you aren't actually looking at space at all. Eventually, you turn your attention back to the app and if you're satisfied enough with the picture, you target something else. You end up with pictures that look impressive when they're small, on your phone, but - owing to their resolution or the unavoidable influence of light pollution - underwhelm when you blow them up on your laptop.

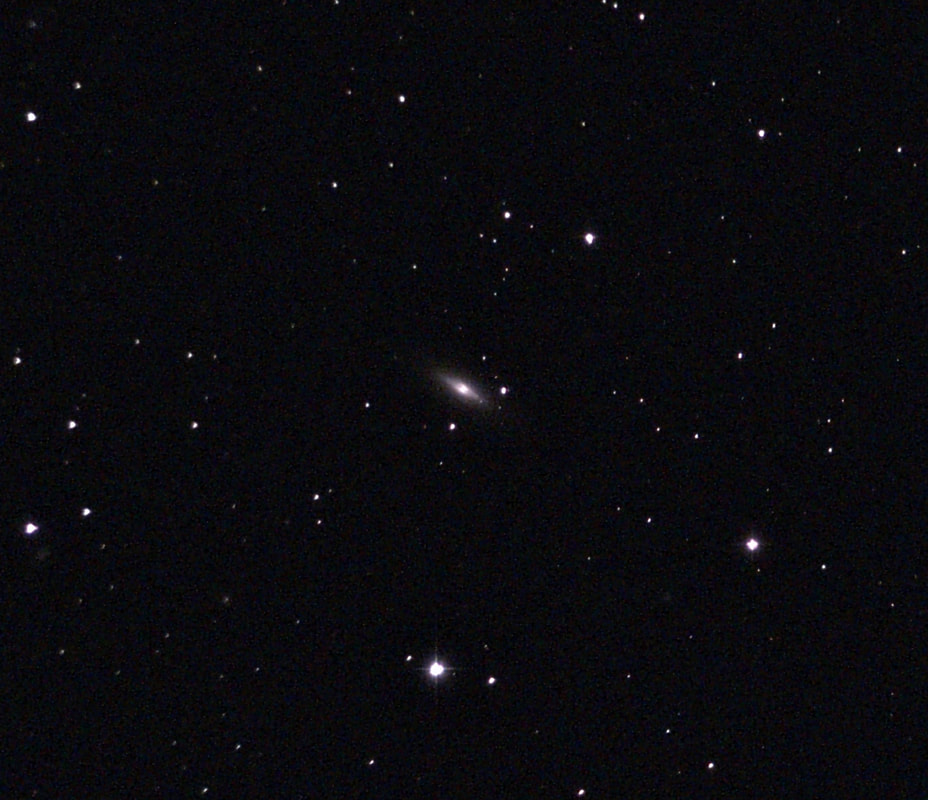

It's exciting to find what's out there, in the sky, that you could never see with traditional optics (barring a difficult-to-use astrophotography setup, of course). But sometimes, walking home, the experience leaves you cold. Sometimes, you feel like all you've done is played with screens. You haven't really experienced nature, and you certainly haven't learned an art. Everything was easy, so occasionally it feels like little was gained. You might as well played with a screen at home. On some nights, the EVScope can feel like a toy - whereas a more traditional telescope always feels like a tool. Maybe that's because of how and where I'm using the EVScope. Maybe the telescope could do more under a darker sky, and certainly the EVScope comes with citizen science features that I haven't begun to access yet. But with the similarly-priced FC 100DZ, for example, I feel like I'm engaging in an old art with a rich history. With the EVScope, I often feel more like I'm playing a game on my phone. Both have their virtues, but if I had to choose one telescope - it would be the refractor. Here in DC, it's hard to avoid thinking obsessively about the demoralizing news from eastern Europe. Yet the skies cleared recently, enough for an hour or two of late-night escapism. A few nights ago, I slipped out with the Takahashi. Transparency was really good but seeing was far worse than average, and since it was well below freezing I didn't want to stay out for long. Still, the FC-100DZ performs so well in poor seeing that I still managed to have a nice view of the waning Moon from my new backyard. Conditions were similar last night, with good transparency and poor seeing. By 10 PM the Moon was only just beginning to rise, which means that the sky was still quite dark. The Big Dipper was climbing towards zenith, and that gave me a chance to image Bode's Galaxy - M81 - with the EVScope 2. I tried imaging M81 with the EVScope 1 on several occasions last year. I have a particular fascination for barred spiral galaxies like M81, which at 12 million light years away is a little smaller than our galaxy. I'm not sure where that comes from exactly, though the shape is certainly aesthetically pleasing. As a kid, I vividly remember admiring a picture of a barred spiral - was it NGC 1300? - that really captured my imagination. Then I found out, when I was a little older, that our own Milky Way was actually a barred spiral, not the conventional spiral it's usually portrayed to be. That was a fun little eye-opener for me. In any case, observing Bode's Galaxy with the EVScope 1 was a disappointment for me. The galactic nucleus is bright enough, but the spiral arms are subtle and easily lost in the downtown DC light pollution. I never got much more than a blurry circle. The EVScope 2 allows me to take longer exposures, however, and that plus its higher resolution made me hopeful of a better outcome last night. And indeed, this is far better than anything I managed with the EVScope 1. To capture this 26-minute exposure from my backyard in downtown DC, after just a few seconds of setup time, seemed borderline miraculous to me. This time, I also peered through the new and improved eyepiece of the EVScope 2. What a huge improvement! Looking through the eyepiece of the original EVScope was like looking down through a barrel at a tiny, pixelated square. But the eyepiece of the EVScope 2 feels like . . . well, a proper eyepiece. The view is circular, it feels close, and it's noticeably higher resolution. In fact, it looks more impressive than the image above. The gallery above shows the difference between unprocessed 9-minute, 18-minute, and 26-minute exposures. The difference is subtle, but it adds up. Note the relative lack of a diffuse glow around the galaxy. With the EVScope 1, that glow used to creep into my exposures after a few minutes, as a result of light pollution here in DC. That's one reason that my views were so much better out of the city. The EVScope is much better at filtering out light pollution, which makes it a far more capable telescope for deep space observing in the city.

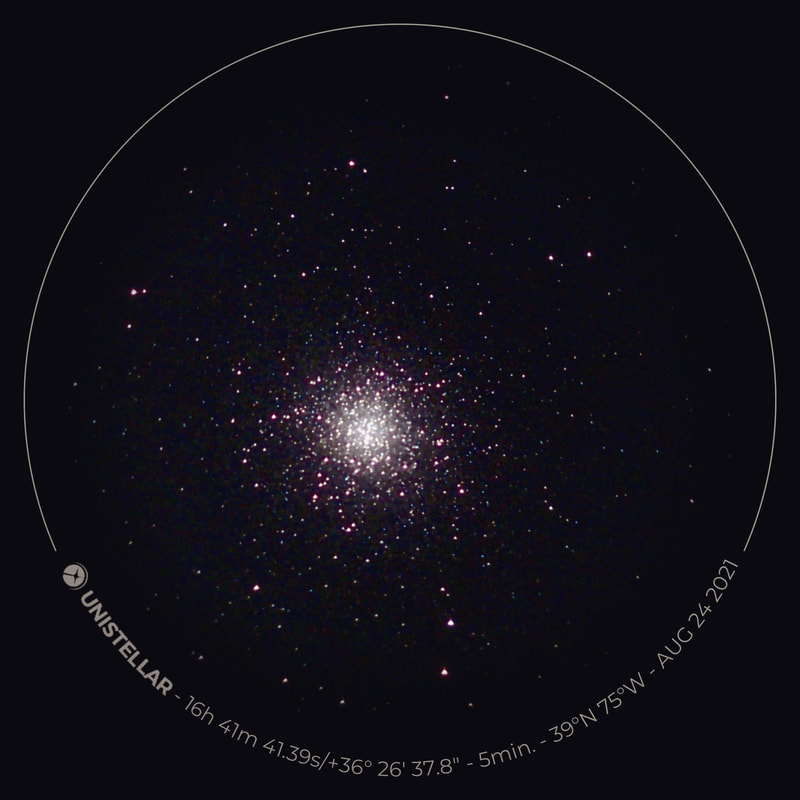

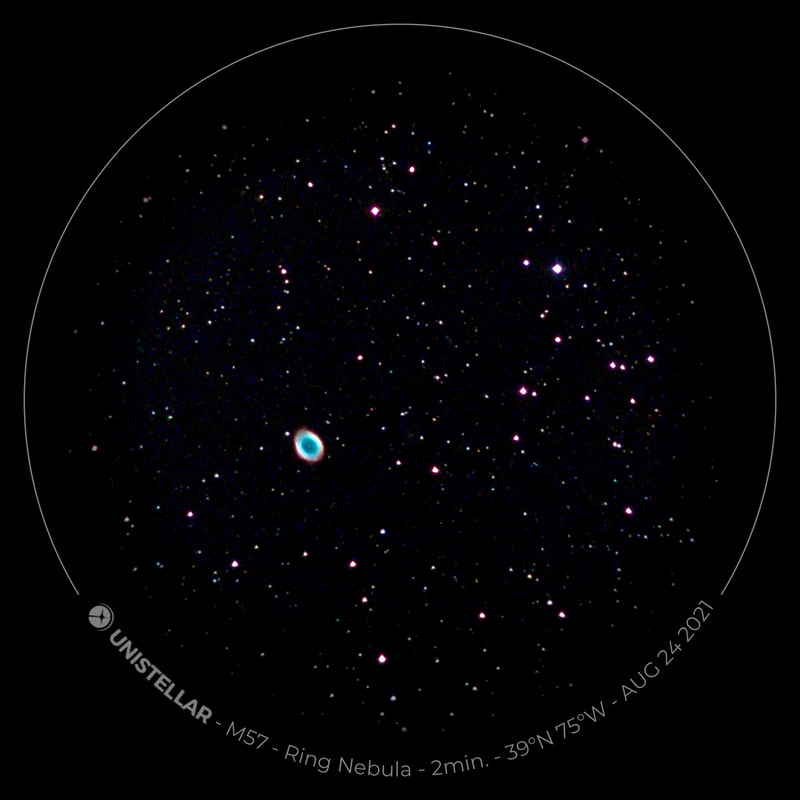

When I ranked the telescopes I'd owned last September, the EVScope 1 came it at number 7. I'd rank the EVScope 2 a good deal higher - definitely in the top five, maybe even the top three. It's that good. Two things have kept me from posting - and observing - these last three months. First: the weather. This has been about the worst stretch of cloudiness and terrible seeing that I can remember in DC. On the rare nights that seemed promising, conditions worsened just as I was about to step outside with my gear. I remember a similar though slightly less atrocious stretch of bad weather last year at around this time, when I was so impatient to see whether my new Takahashi FC-100DZ really provided better views than the Takahashi FC-100DC I had just sold. Now I wonder: is this the start of a new trend, or perhaps a regression to a mean that existed before I started observing whenever I could? But second, I bought a home. That turned out to require a lot of work - more than enough to keep me in, even if the nights had been clear. The new place is a condo with a fenced-in backyard. A backyard! It's what I've always dreamed of. Okay, it's small, and it's mostly for the kids. But when my wife saw the yard for the first time, she reported a gap between the trees that "might be good for your telescopes." My heart skipped a beat. Can you ask for anything more from a partner? We moved in just two weeks ago. It's been quite cloudy since, but then, last night, the clouds parted, and the forecast called for better than average seeing and transparency. So I woke up at 4 AM, ready to go. I didn't have to go far: whereas I've long had to walk for ten or fifteen minutes to reach a nearby(ish) park, now I just step out the back door. What a thrill! Admittedly, the backyard affords only pockets of open sky, nearly all of them facing east-southeast. When the overhanging trees sprout their leaves this spring, most of those pockets will fill up. For now, however, I was thrilled to see Ursa Major, Hercules, and Lyra all hanging overhead. There are some streetlights nearby, but they're not blinding and their light points down at the ground. For a condo backyard, you can't ask for much more. I slipped outside with my EVScope 2. That's right: I've upgraded from my first-generation model. The sequel has a higher-resolution sensor that shows more of the sky, along with a much-upgraded eyepiece. Those were exactly the upgrades that I've yearned for, so when I heard about them I had to pounce. The EVScope 2, however, is not exactly cheap. I bought it at about $1000 more than the original, which of course I had to sell to make the purchase remotely possible. When I stepped outside, it was -7 degrees Celsius - that's about 19 degrees Fahrenheit. To cover the approximately 30 degree (Celsius) delta between inside and outside temperatures, the EVScope required a good thirty minutes to acclimate. When I tried to capture an image before it had cooled down, it was predictably blurry and unsatisfying. But after the telescope had reached ambient temperature, the view was rock-steady. The EVScope 2 seems to align itself even more easily than the original. It honestly takes no more than ten seconds or so, and then it's ready to slew anywhere in the night sky. Objects also appear more consistently centered in my view after the telescope finds them. I'm not sure what accounts for this; is there really something about the EVScope 2 that could be responsible for it? I'm not sure. Maybe I was unlucky with my first unit. But the improvement sure is handy. M51 - the Whirlpool Galaxy - is always a favorite target. Last night it was a little close to the balconies above us, which required me to reposition and realign the telescope a few times to get a decent angle. Then, in just six minutes, I got the above picture. I think it's about as good as the image I got in Lewes, Delaware last summer, with the EVScope 1 under far darker skies. I think the new version handles light pollution far better than the original; certainly it seems to take far longer exposures before the image starts brightening around its edges. The amount of detail on M51 is really extraordinary when you consider it took just a few minutes to get that shot in a light polluted, Bortle 7-8 sky. As readers of this site will know, I get such a kick out of M57, the Ring Nebula. With a four-inch refractor in DC it is just barely - barely - there, and then only with averted vision. A larger refractor shows more, but not much. The EVScope, of course, makes it so obvious, and so colorful, in just a few minutes. The EVScope 2 provides meaningfully less grainy images; the nebula looks smoother here, and much more true to life. As the eastern sky showed its first signs of brightening, I turned to M13, the Hercules Cluster, to close out the night. There's just something about a globular cluster that is always such a thrill for me, and of course the great Hercules cluster most of all. This view did not disappoint: easily the rival, I thought, of what the EVScope 1 revealed under far darker skies. The EVScope 2 seems to more consistently permit longer exposures; I found that my phone frequently lost its connection to the EVScope 1 when my exposures passed ten minutes or so. Maybe that was just my unit, but still: it was nice to easily cruise on to 12 minutes on an object like M13.

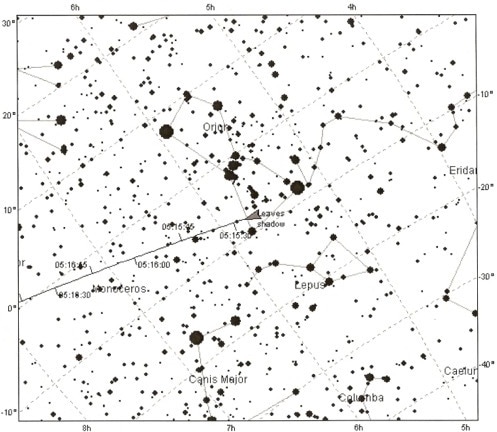

I kept slipping back inside to warm my fingers as the telescope started taking exposures. That's one wonderfully convenient luxury of a backyard. Still, I didn't lose that early morning magic, when all seems still, even in the heart of a city - breathless with anticipation for the rising Sun. There's just nothing quite like that feeling of being outside with a telescope in the hours before dawn, gazing millions of years back in time and space. The sky was that beautiful, robin egg blue yesterday, and sunset faded into an equally clear night. Seeing and transparency were both well above average, so I thought I'd take the TEC 140 out again to have my first look at the Orion Nebula since the spring. Sadly, the hour lost with the daylight saving time adjustment means that the bright planets are now too low in the night sky by the time I can make it out of the house; I'll look for them again in the spring. By midnight Orion was well above the horizon, with Sirius right behind, climbing up out of the glow of the National Mall. After a few minutes telescope and eyepieces acclimated to the crisp evening air. When they did I took out a 10mm Delos eyepiece, and was delighted to find that I could clearly make out six stars in the Trapezium (Theta-1 Orionis) - the little star cluster at the heart of the Orion Nebula - without using averted vision. I've never been able to see the E and F stars so clearly, and I was especially impressed because they were still emerging from the worst of our DC light pollution. The green-blue glow of Orion billowed around those stars, of course, with plenty of nebulosity dimly visible (this time with averted vision) even well beyond the brightest arc of the nebula. As usual, the effect was mesmerizing. Under an urban sky, Orion may be the only nebula or galaxy that looks better through one of my refractors than it does through the EVScope. With a 24mm Panoptic eyepiece I could observe just about the entire sheath of Orion's sword, with the nebula at the heart of it - truly a sublime view. It was getting late by the time I'd had my fill of Orion, so in spite of myself I decided to forego looking at any of the beautiful double stars in the sky right now (except Rigel, an old favorite). Instead I turned to the Andromeda Galaxy, just to remember what it looked like from the city with a truly top-tier refractor. It was a dim blob, of course; no match for what electronically assisted astronomy can reveal. But still, as always a thought-provoking sight.

The march home was painful and exhausting - I had to stop a couple times along the way - but still I was happy to have the season's first view of Orion. Next time with the EVScope, I think. Another clear night on the Atlantic Coast, again with good seeing (but mediocre transparency). Once again I quickly set up my EVScope, and this time I had eyes on the galaxies in the Big Dipper, towards the north, and the Nebulae around the galactic core in the south. The galaxies turned out to be a little disappointing, partly because the EVScope's "enhanced vision" - its image-stacking mode - kept cutting out after just a few minutes. I've had a spotty and unpredictable wifi signal here, which might be to blame. Light pollution is also worse towards the north, and the Big Dipper was low on the horizon. The nebulae to the south, however, were nothing short of spectacular. Below (clockwise from top left) are the Lagoon, Omega, Trifid, and Eagle nebulae, in five- to 10-minute exposures. What really strikes me is the amount of subtle detail in each of these short exposures, especially the dark lanes weaving through each nebula. I took all of these shots, collectively, in about 30 minutes - and then packed up my telescope in around 10 seconds. So, another successful night here in Lewes, Delaware. Now it's back to our light-polluted skies in DC, where my next targets will probably be Jupiter and Saturn.

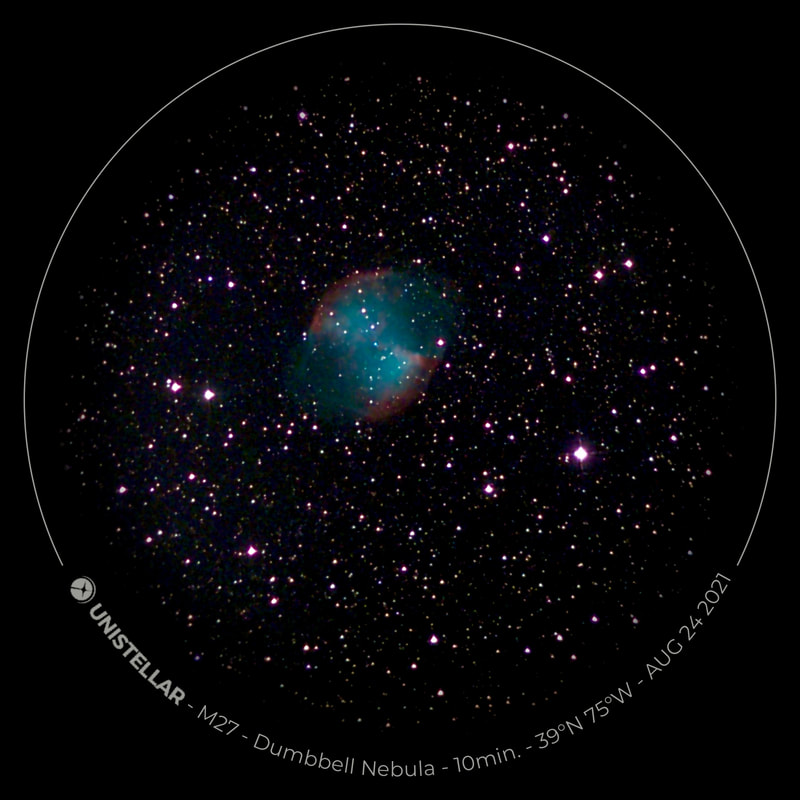

It's been boiling hot and cloudy at night through much of July and August in DC, but this week we escaped to the Atlantic coast. I asked my five-year-old daughter which telescope I should bring, and though Jupiter amd Saturn are high and bright right now she was adamant: the one that would give the best views of nebulae and galaxies. Though I was tempted to bring my TEC 140, the EVScope was the clear choice. I set up the little telescope beneath skies in Lewes, Delaware, that were just about dark enough to reveal the Milky Way. Seeing was really good and transparency was about mediocre. While lying on a hammock in the sun room, I controlled the EVScope and slewed it from one target to another, checking its progress on my phone. You just can't beat that convenience. When there's a lot of light pollution - as in DC - I quickly notice a brightening at the edges of the screen when taking EVScope exposures that are more than a few minutes long. No such trouble here in Lewes, where the light pollution is not comparable to what it's like in DC. I realized things were different right away, with this exposure of the Whirlpool Galaxy. I've written this before, but wow what a thrill to set up a suitcase-sized telescope and, within minutes, observe nebulae in a galaxy 30 million light years away! The more I use the EVScope, the more I find myself thinking that telescopes like it represent a huge part of the future of amateur astronomy. Light pollution is unlikely to get much better any time soon, and attempts to reduce future warming by increasing the opacity of the atmosphere are becoming increasingly plausible (this is known as solar geoengineering). Electronically assisted astronomy (EAA) will help observers overcome these obstacles - while giving them views of the distant universe that simply can't be matched with traditional optics (at least not in a portable package). The technology will only get better, and I can imagine telescopes that can switch seamlessly between modes ideal for Solar System and deep space object observation. While the EVScope can deliver impressive views within the biggest cities, it dawned on me last night that it really comes into its own under darker skies. Perhaps it's no surprise that even EAA follows the same principle as traditional astronomy: the darker the sky, the better the view. The EVScope only reduces - enormously - the usually extreme difference between dark-sky and polluted-sky observing. For example, I've been trying to get a good shot of the Dumbbell Nebula for the longest time in Washington, DC, but whenever I tried I ended up with little more than a disappointing blob. But just look at the view after just 10 minutes in Lewes. To me, the level of detail and color is nothing short of phenomenal. And what a thought: the Dumbbell Nebula is illuminated gas released by a red giant star before its collapse into a white dwarf (in this case, the largest white dwarf known to astronomers). This is what our Solar System could look like in six billion years or so. So yes: when it comes to the EVScope, it's hard to beat the views. And it fits in a tiny corner of my car's trunk, tripod and all!

I've written about the EVScope and Electronically Assisted Astronomy (EAA) quite frequently in these pages. I was skeptical at first - partly because my EVScope had a technical problem - and only came around slowly. Only last night did I become an enthusiastic supporter. I stepped out on a warm, breezy night with the EVScope in its backpack. Transparency and seeing were both around average; there was no Moon. When I reached our nearby park, I set up in all of 30 seconds. I decided that my first target would be the Eagle Nebula, which I've never glimpsed through a regular telescope. The galactic core was lost in light pollution over the National Mall - the sky seemed closer to white than black - so I wasn't optimistic. And yet! When the EVScope found its target - in just a few moments - and started gathering light, a multitude of stars snapped into view, and then the nebula. After a couple minutes, light pollution started to cloud the view - I haven't tried to tinker with the settings that could help me resolve that issue, not yet - so I stopped the exposure after eight minutes or so. I was left with this: In the dark, on my phone, it looked spectacular. Look! There are the pillars of creation - star-making factories so memorably imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope - somehow visible from downtown Washington, DC, just nine or so minutes after setting up in an urban park. This image does it for me - I like my nebulae ghostly and ethereal - but with a little image processing, even more detail pops out (see the picture at the beginning of this post). Now it was on to the Trifid Nebula nearby, it too lost in downtown pollution. Not for long! Again, I'd never seen it with a regular telescope, yet again, it didn't take long to pop into view through the EVScope. This image I like a little less; the unprocessed version doesn't quite bring out the blue. Still, getting this detail so easily in the middle of a city feels nothing short of miraculous. Then it was off to the Ring Nebula which, of course, never fails to impress - albeit in very different ways through an optical versus an EAA telescope. Whether because of a software update or an unusually transparent sky - I suspect the former - I was, for the first time, able to see the white dwarf at the heart of the nebula. Seeing that would require an enormous regular telescope - too big for my car - and a very dark sky. Imagine my wonder at glimpsing the dead star from the city: our Sun's future, six or seven billion years from now. I didn't have much time left, but I wanted to see how far I could reach. I turned to NGC 5907, a galaxy marginally larger than our own, around 54 million light years distant. I could only take a short exposure - I really did have to leave - but there: an edge-on spiral galaxy that I would never have been able to observe even with my TEC 140. The light in this picture left its source not only after the dinosaurs went extinct. What a thought!

I packed up just as quickly as I set up, and then a pleasant walk home with my backpack. It is simply remarkable to see so much so easily. I've often seen the EVScope's hardware discussed and praised, yet what really stands out to me is the software. If only other mounts, carrying regular telescopes, were so easy to use. It seems that the cloudy, turbulent days of winter - in more ways than one - are finally coming to an end. In the wee hours of March 20th, the sky was clear, transparency was (supposed to be) high, and seeing was about average. Conditions, in other words, were about as good as we've had in months. I trotted out with my EVScope, intent on imaging some of the deep space wonders that are now prominent in the early modern sky. After a lightning-quick setup, as usual, I directed my attention to M51, the Whirlpool Galaxy, which is colliding with (and ripping apart) NGC 5195, a smaller galaxy. After a seven-minute exposure, the results impressed me - and for once I noticed that the image looked better when I peered through the eyepiece. Two other galaxies beckoned around the same constellation (Ursa Major, or the Big Dipper): Bode's Galaxy (M81) and the Pinwheel Galaxy (M101). Both are much trickier targets. Bode's bright core is easy to find, but its spiral arms are easily lost; the Pinwheel is big, but has generally low surface brightness. While transparency was supposed to be high, the sky was actually remarkably bright, and I noticed clear halos around street lamps. If anything conditions promised to be poor for both galaxies, and sure enough I wasn't pleased with the results. Here's a three-minute exposure of the Pinwheel Galaxy; you'll see it doesn't exactly impress. That's the thing with the EVScope, and something I haven't seen mentioned in any review: like all telescopes, it performs much better under a dark sky. While there's a lot of hype about how it will reveal deep space objects in the middle of the city, that promise holds up much better for objects that are already bright. Fainter objects can be lost in the glare of light pollution, just as they are in traditional optical telescopes. I'll try these galaxies again when conditions are better, but I don't expect radically different results. By the evening of the 20th conditions had improved dramatically. Both seeing and transparency were now good: a confluence we haven't had here in DC since November, maybe October. Although I was exhausted from waking up early on the previous night, I had to walk out with my Takahashi to catch the Moon while it was still quite high in the sky. As I've written, I've been a little disappointed since swapping my FC-100DC for the DZ, which is supposed to offer slightly better color correction. While I had only used it in nights of bad seeing, I was beginning to worry that it might have been knocked out of collimation in transport. After I set up on the night of the 20th and glanced at the Moon, those worries only grew: the image looks distressingly soft, and I started thinking about how to contact Takahashi. Yet after a few minutes the telescope cooled down, and then: wow. Suddenly the Moon snapped into crystal clear, razor-sharp focus, with absolutely zero false color anywhere - including along the lunar limb, where the slightest undulations and shadows were totally crisp. No matter which eyepiece I used, the detail was spectacular. What stood out the most? Probably the rilles; they seemed to be everywhere, and so delicate that they looked like veins on a living thing. After a little while I concluded that the view seemed best with my 6mm Delos at 133x. At that magnification I could still see the entire Moon, but I was close enough to make out truly breathtaking detail, in every conceivable shape and form. It truly felt as though I was looking out the window of a spaceship, approaching the Moon after a long journey from Earth. There are times when the atmosphere cooperates, and something spectacular is in the night sky, that it doesn't take long for me to have my fill; to feel as though I can't take in any more, because I just want to savor and remember what I've seen. So it was this night. After about 40 minutes, I packed up and walked home. So yes, the FC-100DZ is an extraordinary telescope. To me, it has a bit less false color than the DC and significantly less than the TV-85, although both of those telescopes really had very little, and that gives it a small edge in sharpness. The difference is subtle but noticeable - on nights of good seeing. Of course, those night don't come along very often, and I've found that on most clear nights the state of the atmosphere matters far more than slight improvements in instrumentation. The FC-100DZ's bigger improvement over the DC, as I've written, is probably its modest but meaningful mechanical upgrades. Still, owing fine refractors has made me a little obsessive about the details, and for me the move from a DC to a DZ appears to have been worth it. That's a relief! |

Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed