|

Our indefatigable news media seems to have transformed every full Moon into a show-stopping event. It's always a super blue wolf harvest something or other. To be fair, the hype stirs up a good deal of popular interest in our neighboring world, and to my mind that can only be a good thing. Of course, amateur astronomers know that because a full Moon has no shadows, it can be unsatisfying to observe with a telescope. The craters, mountains, and rilles that are otherwise so obvious seem washed out in a sea of milky-white brilliance. Still, the trees in my backyard have not yet unfurled their budding leaves, and pockets of the night sky remain visible just steps from my kitchen. The other night, I couldn't resist setting up my Takahashi TSA 120 as the full Moon moved through a gap in the bare branches. Atmospheric transparency and seeing were both about average - at least in theory. In practice, conditions seemed to shift by the minute. Occasionally a watercolor softness blurred the Moon, but then it snapped into focus for many seconds at a time. For amateur astronomers, our atmosphere truly is a fickle antagonist. Using my iPhone, I don't believe I managed to get a picture of the Moon in its clearest moments. Still, just look at those mountains outlined in sharp relief on the limb of the Moon. Rarely have I managed to get such an obvious look at them. Crater rays, meanwhile, are actually a lunar feature that becomes obvious only with the Moon fully illuminated. It was wonderful to follow their tendrils across the the Moon's silvery regolith. As for the telescope, what is there to say? Among apochromatic refractors, the TSA 120 is about as perfect as it gets. Nitpicking comes easy to me, but in this case there are no nits to pick. Actually, the telescope's size reminds me a little of the Vixen ED115S that I used to own (with its oversized Moonlite focuser). I thought the Vixen was the perfect size for a refractor, but the TSA might be even better. It actually feels a bit lighter and more compact, but the aperture is just a bit bigger. A five-inch refractor is a really ideal: it edges out the performance of a four-inch, but doesn't need a much bigger mount and tripod (which can be necessary with just half an inch of extra aperture). I recently acquired a DSV3 mount from Desert Sky Astro. This is a manual mount that isn't too heavy and seems extremely well made. It includes both slow-motion controls and a handy "quick balancing system" that allows you to easily compensate for the weight of different eyepieces. With just a flick of the wrist, the telescope stays balanced. It's a clever little feature that, I discovered last night, makes observing just that much easier.

Readers will know that I'm a manual mount aficionado. When you don't have much time to observe, or if you want to avoid all hassle in a public park, there's simply nothing better. So far the DSV3 seems like the best medium mount I've used, and I've tried just about all of them. It's at least as well made as the best mounts on the market, and it includes features that its competitors simply don't offer. For the TSA 120, it truly is just about perfect. After I'd observed for no more than 30 minutes, the Moon rolled behind my building, and with fingers numb from cold I packed up my telescope. As I've mentioned here before, it's hard to think of a better use of time than exploring another world from the comfort of your backyard.

0 Comments

If November isn't my favorite month to observe here in Washington, DC, it's right up there with March and April. Most nights are cool, crisp, and imbued with an ineffable fragrance - of decaying leaves in autumn, of budding blossoms in spring - that encourages deep breaths. The mosquitoes are resting after (or before) the horrors of summer, and seeing hasn't yet slumped to its winter lows. I try to use my telescopes as much as I can in late autumn and late spring, but there's a problem: these are the busiest times in the academic calendar, and it's not always easy to juggle my hobby with my work. Worse, both seasons are times of unrelenting illness for any parent with young children. So it is that while the sky has been routinely clear for the last month, with seeing typically average, I haven't had much chance to exploit it. Finally, on November 13th, I felt just healthy enough to venture outside with my TSA 120. At just before midnight, Jupiter was nearing zenith. Although atmospheric conditions were not exactly ideal, I couldn't pass up the chance to have a look. I had let my TSA 120 sit outside for about 45 minutes before using it, and it paid off: while temperatures were no higher than 10 degrees Celsius, the telescope had completely cooled down. Yet when I turned to Jupiter, the planet initially resembled a circle of bubbling milk, surrounded by a smattering of drops (the Galilean moons). Why had I sacrificed sleep for this? Then, as I considered packing up, the atmosphere abruptly stabilized - and now a staggering wealth of detail shimmered into view. It was fleeting - "revelation peeps," to use a Lowellian term, often are - but it was more than enough to keep me glued to the eyepiece. Over the next hour, belts, zones, and the Great Red Spot all flickered across the pale Jovian disc, and I nearly lost track of time. Finally, it dawned on me that even a bad night's sleep was slipping away, and I hastily carried my equipment inside. Perhaps it's a character flaw that I like to obsessively compare my instruments; if so, it is a flaw I share with most amateur astronomers. In this case, I couldn't help but reflect on the TEC 140 I once owned. In a vacuum, I might prefer that telescope over the TSA 120. But the difference in the optical performance of both telescopes is slight enough that I prefer the far greater portability of my TSA 120 setup. It weighs half as much, and that makes it so much easier to use when I'm tired. Of course, when it comes to portability and ease of use it's hard to beat my EVScope 2. With Orion starting to rise high above the horizon in the wee hours of the night, I decided to use that telescope to view the constellation's famous nebula. On the 18th I parked the telescope in my backyard, found a gap in the increasingly bare trees, and had a look. As usual, within seconds the EVScope delivered a view that no traditional telescope could match under an urban sky. Yet using the telescope so soon after observing with my TSA 120 gave me a clear sense of what bothers me about it. The EVScope is easy. There are no "revelation peeps" - no flashes of transcendence - because everything is smoothed out in a (relatively) pretty picture. There's no craft to observing, no sense of taking in the universe with your own eyes. You see more - but you feel less. Sometimes, that's okay. There are whole classes of object - white dwarfs for example - that I can only glimpse with my EVScope (at least in our light-polluted skies). Yet if I were forced to give up one telescope, I would choose the EVScope without a second's hesitation. My health improved this week, and my workload (temporarily) eased. Now I steeled myself for a challenge I've dreaded for weeks: collimating my new Mewlon 210. I've been so unwilling to try it that I even - very briefly - placed the telescope for sale. Yet I read up, prepared my Allen key - and left the Mewlon out for an hour to cool down.

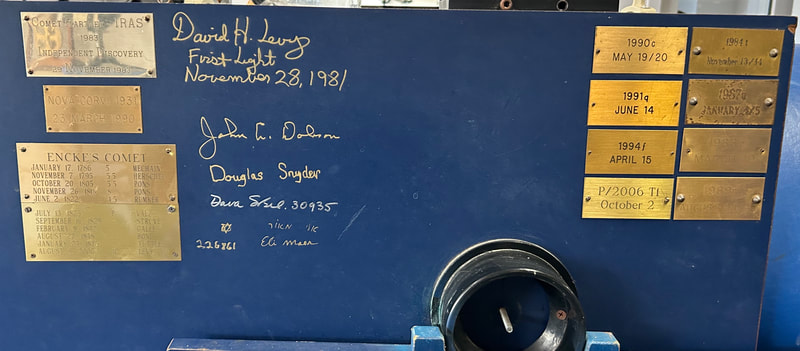

When I returned outside, I found that the telescope still had not completely acclimated to temperatures that were not far above freezing. I waited another half hour, then tried again. Now the telescope seemed cool enough, but to my surprise my first view of a star was so underwhelming that I again considered whether to sell the telescope. A blob is the best I could get - a far cry from the pinpoints I see through my refractors. I'd hoped that I'd been wrong about the Mewlon's collimation, but now there was no doubting it: the telescope's secondary mirror simply did not perfectly align with the primary. I set to work tightening bolts, and to my surprise I didn't mind it. Years of tinkering with mechanical watches and bicycles had prepared me well, I suppose, because after 15 largely painless minutes I was just about done. I could scarcely believe my eyes when I returned to that star. Instead of a blob, there was a perfect little diamond. To my amazement, the telescope's diffraction spikes - a product of the four vanes that hold its secondary mirror - actually added to the star's beauty. It wasn't perfect - seeing was actually below average - but it was about as beautiful a stellar image as I can remember seeing. Jupiter offered some of the same revelation peeps I'd enjoyed with my TSA 120, except with a bit more color (and this time, the diffraction spikes were a bit distracting at lower magnifications). Turning to the Trapezium in Orion clearly revealed five, perhaps six stars - a challenge for fine optics even in good seeing - but it was Betelgeuse that truly stole the show. The star was simply a spectacularly beautiful orange gemstone when viewed through the Mewlon. The telescope's large aperture (compared to my refractors), total lack of false color, and yes, diffraction spikes made me appreciate simple stars as I never have before. With any luck, I'll use the Mewlon to spend happy hours admiring the double stars that are easily visible in our city. But on this night, it was time to pack up - and to banish all thought of selling the Mewlon. It was midnight on September 1st, and the atmosphere was about as good as it gets for stargazing here in Washington, DC. Transparency was high, seeing was great, Saturn was high in the sky and Jupiter was wheeling over the horizon. My had prepared my TEC 140 in the living room, and prepared to haul it outside. I knew I'd have to walk for a few minutes, and I tried to figure out how best to do it. The telescope itself is just over 20 pounds. The DM-6 mount that holds it well? With its extender, also just north of 20 pounds. The Planet tripod that keeps it all stable? Another 27 pounds. With my eyepieces and including all the cases and bags that house the gear, I was looking at hauling more than 80 pounds. That might have seemed doable were it not for the size everything took up. I simply could imagine no way to drag my gear to my only nearby observing site in fewer than two - possibly three - walks. It had been a long day at work, and I was still tired from recent travels. I left my gear in place. There would be other nights. The next morning, it dawned on me that something was out of whack. Since my little backyard faces north and is usually too shrouded by leaves to be useful for astronomy, I need to be able to easily transport my gear to a more suitable spot. Last year I bought a wagon to make that easier, but dragging it around turned out to be nearly as difficult as carrying my equipment. Given my need to walk to observe, I'd long ago decided that my heaviest telescope would be a medium-sized refractor, and the TEC seemed like the best option available. Somehow, however, I'd ended up with a heap of gear that was almost impossibly heavy to walk with. What happened? Well, it turns out that in amateur astronomy - as in many other things - a sufficient number of little changes can collectively create a new paradigm. The trouble was that the TEC 140 is just a bit heavier and (especially) longer than a medium-sized mount can handle, and that required a big, hulking DM-6. Both DM-6 and TEC 140 are also just a bit too heavy for a medium-sized tripod, especially on a hard surface. Enter the Planet tripod. A medium-sized telescope therefore required gear that was heavy enough to hold something much larger. Yes, it was beautifully stable once set up. But that didn't mean much if it was too massive to move. With a heavy heart, I put my TEC 140 up for sale. Within hours, a friendly local buyer had scooped it up. While I was, on some level, sorry to let it go, it also struck me that I'd made few genuinely special memories with it. I tend to grow attached to instruments that have genuinely shown me something new. My dearly-departed TV 85, for example, revealed just how much sharper a refractor could be in our DC weather than any other kind of telescope - and gave me my first unambiguous view of the Great Red Spot. My Takahashi FC 100DC gave me truly unforgettable views of Mars, and the shadows of Jupiter's moons. My APM 140 gave me even more stunning views of Mars and Jupiter, and then the 100DZ left me breathless while gawking at the Moon. The TEC 140 did give me a wonderful sensational of texture in the Jovian clouds. But that wasn't quite enough to build a bond. After I sold my now-useless DM-6 and Planet tripod, I had some decisions to make. Should I downsize by, for example, buying a jewel-like Questar 3.5? I opted it against it after reading convinced me that the iconic little telescope could simply not compete with the also-portable 100DZ. I opted to attempt to buy two lighter but still medium-sized telescopes that I hoped could largely replace - or even improve upon - the capabilities of the TEC, while requiring a much lighter tripod and mount. The first of those telescopes: a TSA 120. Takahashi's four-inch refractors have long been my favorite telescopes. I decided to try something a little bigger in the five-inch TSA 120, an air-spaced triplet (a refractor with three lenses) that, I thought, could gather meaningfully more light than the 100 DZ. I'd long resisted buying an air-spaced triplet, since these telescopes weigh more than doublets and take much longer to cool down. The weight of the TSA 120, however, splits the difference between the TEC 140 and 100 DZ, and I figured I could simply let it acclimate in my backyard before carrying it to a more suitable observing site. To my delight, I managed to buy the TSA 120 on sale. When it arrived, I was immediately surprised by its compact size. Although its aperture is just a bit lower than that of the TEC 140, its dimensions seem closer to those of the 100DZ than the TEC 140. I also had not expected it to ship with a quality two-speed focuser. You can purchase the telescope with the bulkier but ostensibly more precise Feathertouch focuser, but Takahashi's equivalent is, to my mind, just about as good. Truth be told, I don't really understand the obsession with replacing the focusers on premium telescopes, like the Takahashi refractors. All you need is something that gets the telescope in focus, and to my mind the stock focusers do that very well. It's a small point and one I've brought up before, but still: I can't get enough of the Takahashi aesthetic. The white tube, black trim look is classic for a reason, but here's to doing something a little different. I think Ed Ting once mentioned that Takahashi telescopes have an indefinable Zen character to them, and that feels about right. It makes me inexplicably happy to see them. That's not to say that the build quality of the TSA 120 exceeds that of the TEC 140, but I do prefer that cream-colored paint with mint-green accents. Anyway, on September 14th the sky cleared and temperatures cooled just after I'd finished setting up my new TSA 120 (with Moonlite tube rings courtesy of a very helpful veteran of the Cloudy Nights forum). By then, I'd found that my Berlebach Uni tripod and (wonderful) NoH's Mount CT-20 easily support the TSA 120, which made for a setup that weighs about 40 pounds total - half as much as the TEC 140 and its equipment! I bought a Stellarvue C9S case for the TSA 120 that fits it exceptionally well, and I left the telescope outside, in its case, for about 40 minutes before using it. This time I easily walked to my nearest observing site, in the courtyard of my building. Saturn is just about a month past opposition, and high above the horizon at about 11:00 PM. I decided that its light would be the first that entered my new telescope. I have a strange relationship with Saturn. To me, it's still the most impressive object in the night sky. Yet as a target for repeat observation, it pales in comparison to Jupiter and Mars. Its rings change their tilt over time, sure, but I can rarely make out enough detail on its disk to give me the impression that I'm viewing an evolving world. Well, the TSA 120 might change that. At about 90x with my Delos 10mm eyepiece, Saturn was spectacularly well defined. I'm not sure I've ever seen such fine detail in the grey clouds above its rings. The outline of its rings was razor-sharp, the Cassini division clearly outlined. It was, I decided, about the best view I've had of the planet. Mosquitoes started to emerge, whining near my ears, but I was so distracted that I soon found myself covered in bites. I packed up and walked back home - easily. When I got inside, I was a little taken aback. I wasn't sure exactly how my view of Saturn compared to the best I had with the TEC 140; almost exactly two years ago I marveled in these pages that the bigger refractor gave me an "absolutely stunning" look at that planet. And yet, I couldn't say while unpacking the TSA 120 that I'd ever had a better view of Saturn. The sharpness is what most impressed, and the collection of bright little moons, swarming around the planet like moths around a lantern. Granted, both seeing and transparency had seemed better than average. But if the TSA 120 gave me a view that left me so satisfied, why had I hauled around so much more weight for so long? On September 15th, the pellucid evening sky invited another round with Saturn. This time, I brought out the second telescope I'd purchased: a Mewlon 210. These unusual Dall-Kirkham telescopes are a little like condensed Newtonian reflectors, with very long focal lengths. They cool down more quickly than other catadioptric telescopes - like the ubiquitous Schmidt–Cassegrain - and have none of the dew problems that can hamper these telescopes in a humid environment (Washington, DC certainly qualifies). Takahashi makes its Mewlon variants to exacting specifications, and that should in theory make them exceptional planetary telescopes. They are famously tricky to collimate, however, and they must be perfectly collimated to realize their potential. They also take a lot longer to cool down than (smaller) refractors, and their field of view is much narrower. They are much more sensitive to poor or mediocre seeing than those refractors, and the vanes that hold their little secondary mirrors produce faint rays around bright objects. The Mewlon is, therefore, a specialist instrument. Yet when conditions are right, all Mewlon variants are designed to give spectacular views of the Moon, planets, and double stars: precisely those objects I most enjoy observing in the city. At over eight inches in aperture, in good seeing the Mewlon 210 should in fact reveal those objects with even greater brightness and detail than the TEC 140. And - remarkably - it weighs much less than that telescope, despite looking much heavier. On that note, I will add that, in my view, the Mewlon 210 is quite possibly the most impressive amateur telescope to look at. It is simply beautiful. It looks like a jet engine crafted with care by a Swiss clockmaker. What's more, it comes complete with a finder scope that stays perfectly aligned with the telescope, and is so robust that you can use it as a handle. You may have to collimate the telescope from time to time, but you never have to align the finder - and that makes up for a lot. So how did the Mewlon perform on Saturn? Sadly: not as good as the TSA 120. It was clear from the box that the telescope had been handled roughly on its way to me, and something - or someone - had knocked it out of collimation. All the same, it was only a little off, and I hope I can tweak it to perfection sometime soon. Maybe in my backyard, after the leaves finally fall? Remarkably, atmospheric seeing and transparency were again above average last night, so I stepped out again with my TSA 120. This time, I waited until about midnight, when Jupiter had climbed above the horizon. I turned to Saturn first, and now the view was truly breathtaking: slightly but meaningfully more vivid - more crisp - than I'd seen even a couple nights earlier. I quickly switched to a 4.5mm Delos, giving me a magnification of exactly 200x. In my experience, Washington's sky rarely allows that kind of power. Yet to my astonishment, the atmosphere repeatedly settled down to allow a remarkably sharp view at that magnification. The subtle mingling of grey, beige, and buttermilk threads in the planet's atmosphere was simply a joy to tease out, and I could make out glimpses of structure in its ring system that I'm not sure I've ever seen before. Was this my best-ever view of Saturn? I concluded that it probably was, and again I was so enthralled that I lost track of the mosquitoes biting me. Eventually I wheeled the telescope around to Jupiter, and now the view was a little softer. The planet was still climbing out of (Earth's) thicker atmosphere near the horizon, and seeing seemed less stable in its corner of the sky. Still, I routinely made out wonderfully delicate detail in its many belts and zones. It's a little silly to compare the view through different telescopes on different nights, and perhaps sillier still to compare exceptional refractors to one another. Yet even (or perhaps especially) the most unscientific comparisons are fun, and in this case I think they're instructive. On my nights of observing, I judged that the TSA 120 showed just a bit less contrast - on Jupiter especially - than the TEC 140, and perhaps the APM 140 I once had. Yet it showed more contrast than the 100DZ - the planets seemed just a bit more vibrant - and the views were just as sharp; sharper than anything I could remember seeing through the bigger refractors. I was particularly impressed by how easily the TSA 120 snapped into focus, and how readily it gobbled up magnification. On both fronts, it seemed to exceed the performance of any telescope I've tried using. Now, all the usual caveats about the atmosphere certainly apply, but that's the point. When telescopes get to a certain quality and size, it's often factors beyond the performance of their optics that are most important. I truly did love my TEC 140. Yet I can't conclude that it's superior to the TSA 120. Both telescopes have brilliant optics that, in Washington DC, are almost invariably limited by the atmosphere, rather than their innate capabilities. Yet a setup that supports one telescope is fully twice as heavy as the other. When you're tired at the end of a long day, it doesn't take much to discourage even a quick observing session. With that in mind, the lighter, more portable setup is more often the best one. At least, it seems like it is for me. I know this is a long entry, but I can't conclude without mentioning a recent trip to the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada archive in Toronto. Since I was last there, the society's staff have set up several dozen telescopes that had me feeling like a kid in a candy store. There were two beautiful Unitron refractors, an exceptionally long Antares achromatic, a huge Cave reflector . . . the list goes on. But one in particular stood out - the ugliest one, by a long shot. Yes, that's David Levy's trusty telescope: a makeshift Dobsonian reflector complete with duct tape and what looks like a jar (!) over a finder scope. Plaques commemorating discovered comets line its base like kills on a Spitfire. Here was a poignant reminder that the best telescope - or indeed the best machine of any sort - is the one that works for you, and you alone.

|

Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed