|

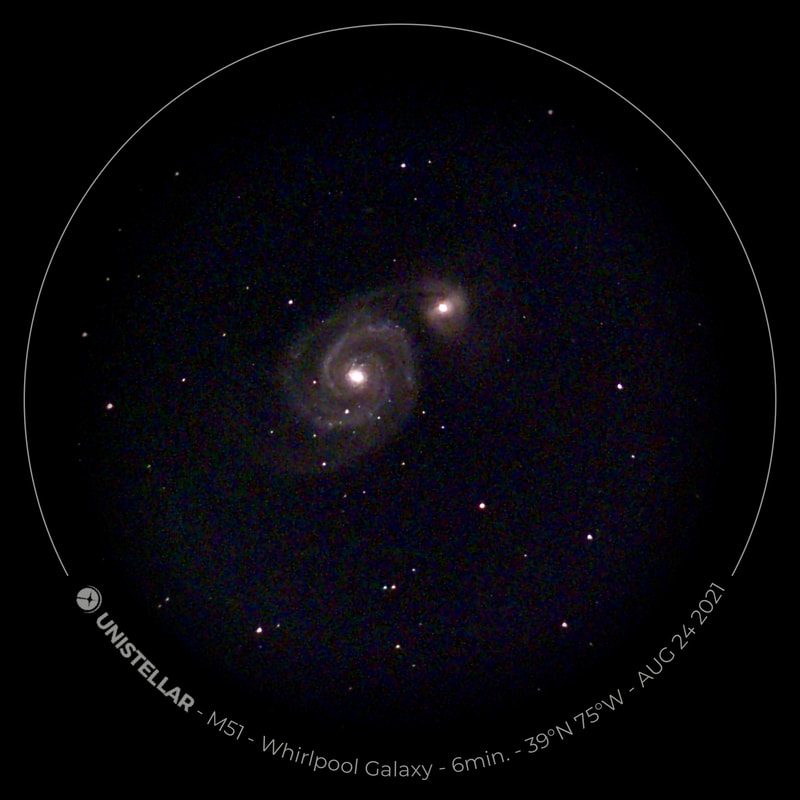

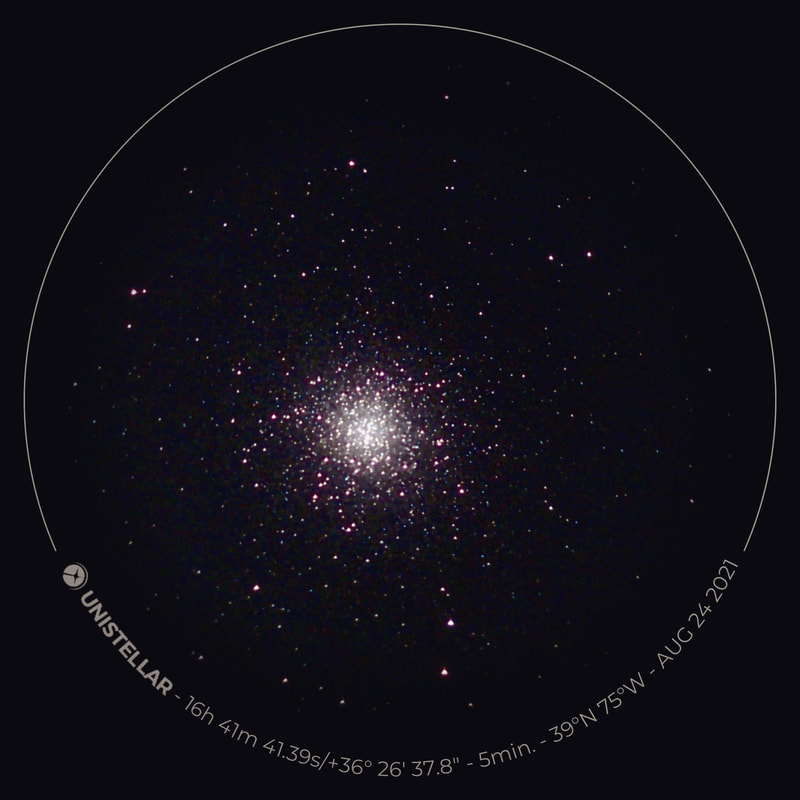

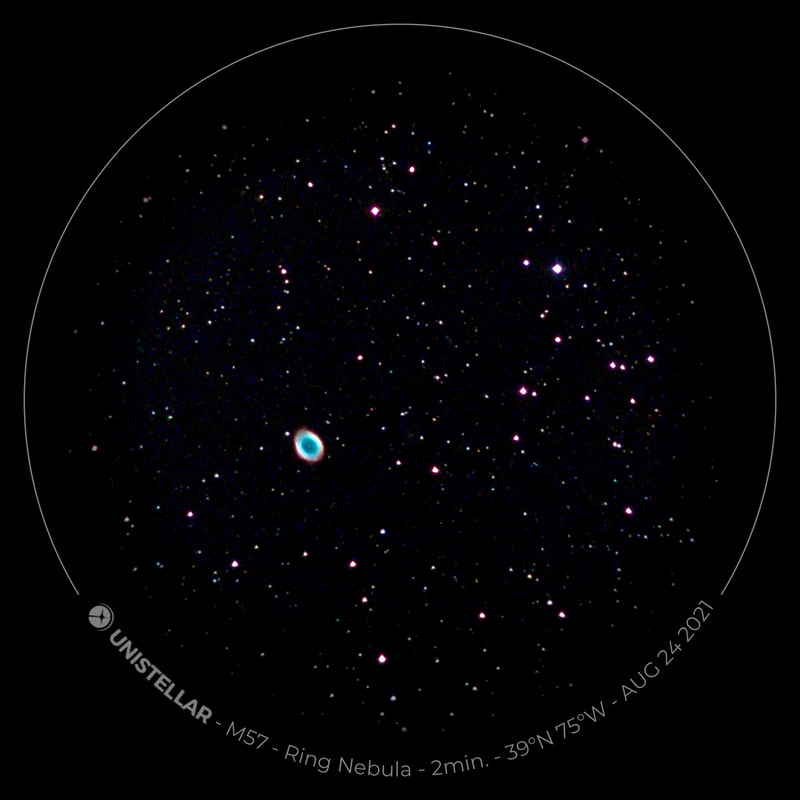

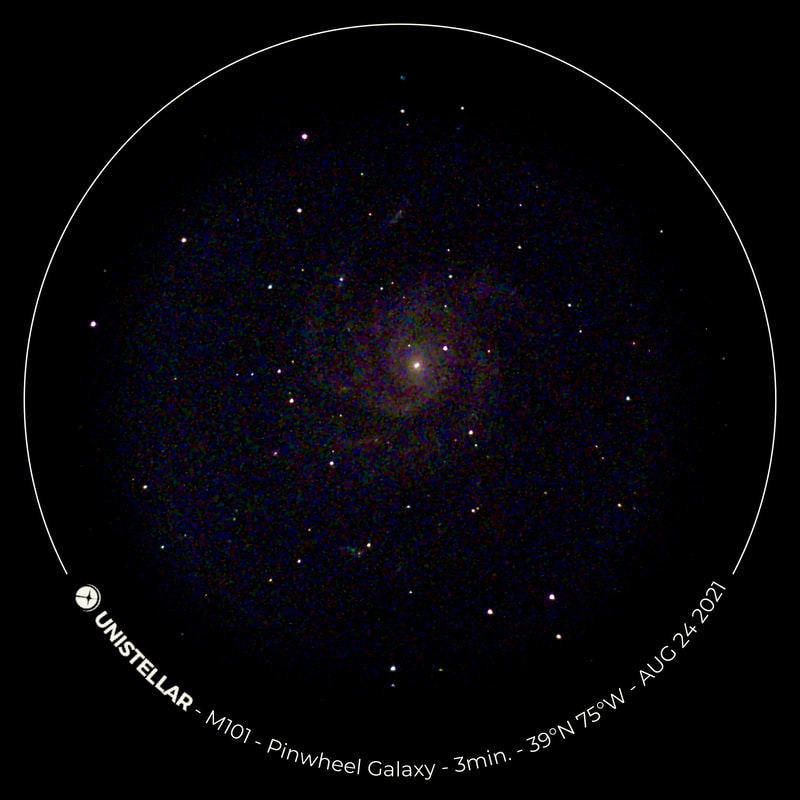

Two things have kept me from posting - and observing - these last three months. First: the weather. This has been about the worst stretch of cloudiness and terrible seeing that I can remember in DC. On the rare nights that seemed promising, conditions worsened just as I was about to step outside with my gear. I remember a similar though slightly less atrocious stretch of bad weather last year at around this time, when I was so impatient to see whether my new Takahashi FC-100DZ really provided better views than the Takahashi FC-100DC I had just sold. Now I wonder: is this the start of a new trend, or perhaps a regression to a mean that existed before I started observing whenever I could? But second, I bought a home. That turned out to require a lot of work - more than enough to keep me in, even if the nights had been clear. The new place is a condo with a fenced-in backyard. A backyard! It's what I've always dreamed of. Okay, it's small, and it's mostly for the kids. But when my wife saw the yard for the first time, she reported a gap between the trees that "might be good for your telescopes." My heart skipped a beat. Can you ask for anything more from a partner? We moved in just two weeks ago. It's been quite cloudy since, but then, last night, the clouds parted, and the forecast called for better than average seeing and transparency. So I woke up at 4 AM, ready to go. I didn't have to go far: whereas I've long had to walk for ten or fifteen minutes to reach a nearby(ish) park, now I just step out the back door. What a thrill! Admittedly, the backyard affords only pockets of open sky, nearly all of them facing east-southeast. When the overhanging trees sprout their leaves this spring, most of those pockets will fill up. For now, however, I was thrilled to see Ursa Major, Hercules, and Lyra all hanging overhead. There are some streetlights nearby, but they're not blinding and their light points down at the ground. For a condo backyard, you can't ask for much more. I slipped outside with my EVScope 2. That's right: I've upgraded from my first-generation model. The sequel has a higher-resolution sensor that shows more of the sky, along with a much-upgraded eyepiece. Those were exactly the upgrades that I've yearned for, so when I heard about them I had to pounce. The EVScope 2, however, is not exactly cheap. I bought it at about $1000 more than the original, which of course I had to sell to make the purchase remotely possible. When I stepped outside, it was -7 degrees Celsius - that's about 19 degrees Fahrenheit. To cover the approximately 30 degree (Celsius) delta between inside and outside temperatures, the EVScope required a good thirty minutes to acclimate. When I tried to capture an image before it had cooled down, it was predictably blurry and unsatisfying. But after the telescope had reached ambient temperature, the view was rock-steady. The EVScope 2 seems to align itself even more easily than the original. It honestly takes no more than ten seconds or so, and then it's ready to slew anywhere in the night sky. Objects also appear more consistently centered in my view after the telescope finds them. I'm not sure what accounts for this; is there really something about the EVScope 2 that could be responsible for it? I'm not sure. Maybe I was unlucky with my first unit. But the improvement sure is handy. M51 - the Whirlpool Galaxy - is always a favorite target. Last night it was a little close to the balconies above us, which required me to reposition and realign the telescope a few times to get a decent angle. Then, in just six minutes, I got the above picture. I think it's about as good as the image I got in Lewes, Delaware last summer, with the EVScope 1 under far darker skies. I think the new version handles light pollution far better than the original; certainly it seems to take far longer exposures before the image starts brightening around its edges. The amount of detail on M51 is really extraordinary when you consider it took just a few minutes to get that shot in a light polluted, Bortle 7-8 sky. As readers of this site will know, I get such a kick out of M57, the Ring Nebula. With a four-inch refractor in DC it is just barely - barely - there, and then only with averted vision. A larger refractor shows more, but not much. The EVScope, of course, makes it so obvious, and so colorful, in just a few minutes. The EVScope 2 provides meaningfully less grainy images; the nebula looks smoother here, and much more true to life. As the eastern sky showed its first signs of brightening, I turned to M13, the Hercules Cluster, to close out the night. There's just something about a globular cluster that is always such a thrill for me, and of course the great Hercules cluster most of all. This view did not disappoint: easily the rival, I thought, of what the EVScope 1 revealed under far darker skies. The EVScope 2 seems to more consistently permit longer exposures; I found that my phone frequently lost its connection to the EVScope 1 when my exposures passed ten minutes or so. Maybe that was just my unit, but still: it was nice to easily cruise on to 12 minutes on an object like M13.

I kept slipping back inside to warm my fingers as the telescope started taking exposures. That's one wonderfully convenient luxury of a backyard. Still, I didn't lose that early morning magic, when all seems still, even in the heart of a city - breathless with anticipation for the rising Sun. There's just nothing quite like that feeling of being outside with a telescope in the hours before dawn, gazing millions of years back in time and space.

0 Comments

We've had some clear skies over the past week, and of course for me that involved hauling my telescopes outside. With Jupiter and Saturn high above the horizon early in the evening, now is a great time for planetary observation. I set up my Takahashi FC-100DZ on our rooftop one night, but although it was convenient - and the National Mall looked spectacular in the distance - plumes of heat rising from our building marred the view. Jupiter was a boiling mess, and Saturn looked only slightly better. Smoke from the west coast wildfires moved in early this week, so the transparency of the sky plummeted. Yet seeing was above-average, and - knowing that a little haze in the sky can sometimes improve planetary views - I stepped out anyway, Takahashi in hand. I mount the telescope on a DiscMounts DM-4, and although the mount should easily be able to hold the Takahashi with minimal vibration, so far its stability doesn't compare to that of the AYO II I recently sold - even on my heaviest tripod. Perhaps I need to play around with the tension? I suppose I'll keep experimenting. I wasn't prepared for the thickness of the wildfire smoke at high altitude - yes, that's more than a little depressing - and so Jupiter and especially Saturn were dimmer than I'd anticipated. Yet seeing was, at times, phenomenal. All of Jupiter's moons were visible, and all looked like clear disks of varying color and size. Orange Io and giant Ganymede were especially easy to pick out at 177x, and for once I wished I had more magnification (unfortunately, I'd left my Nagler zoom eyepiece at home). On nights of bad seeing, one two dark belts can be visible on Jupiter. Now, I saw some spectacular detail. Not only were the two northern and two southern temperate belts plainly visible, but I could make out delicate, at times feathery texture all along each belt. I lingered a while on that view. Saturn, unfortunately, was less impressive: the smoke was just too thick to permit more than a dim view. On a night with higher transparency, I walked out with my EVScope. I confirmed what I'd long suspected: in a light-polluted urban sky, brightening at the edges of the view precludes long exposures. While you can still get impressive urban (!) views of many nebulae, star clusters, and galaxies, the telescope performs much better when the light pollution isn't as bad.

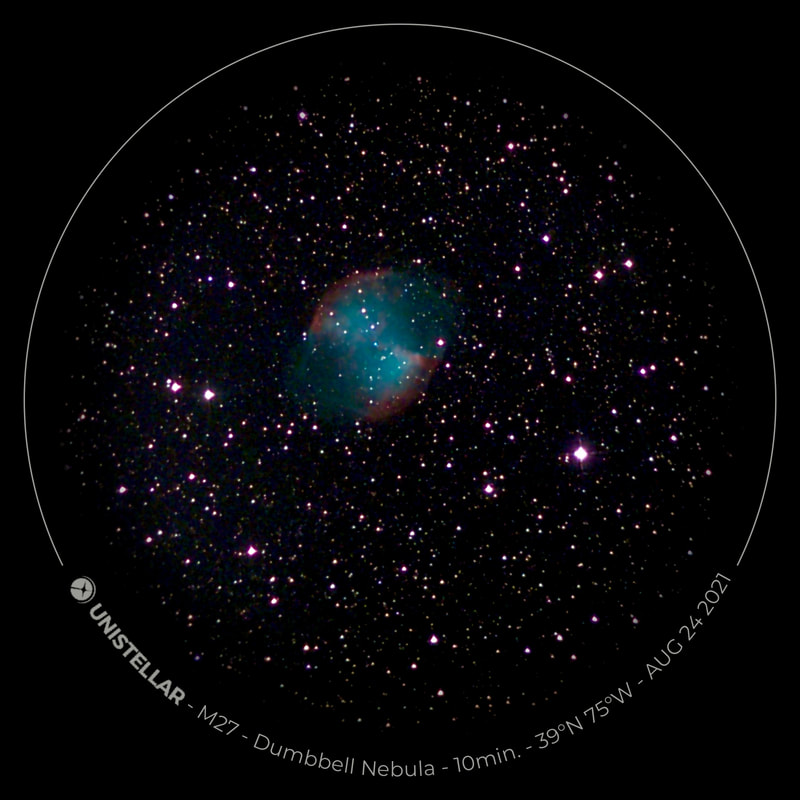

The comparison above shows what the EVScope can do under a suburban sky (top) and in ideal conditions under an urban sky (bottom), with similar exposure times. It should be stressed that conditions for the bottom image were truly ideal: the nebula was near zenith, there was no Moon, and transparency was excellent. Still, it's clear that the telescope goes a bit deeper when the light pollution is lower. Of course, I also could have had a much longer exposure under that suburban sky, had I wanted to do that. All in all, two good nights of very different observing - and one pleasant view from our rooftop. It's been boiling hot and cloudy at night through much of July and August in DC, but this week we escaped to the Atlantic coast. I asked my five-year-old daughter which telescope I should bring, and though Jupiter amd Saturn are high and bright right now she was adamant: the one that would give the best views of nebulae and galaxies. Though I was tempted to bring my TEC 140, the EVScope was the clear choice. I set up the little telescope beneath skies in Lewes, Delaware, that were just about dark enough to reveal the Milky Way. Seeing was really good and transparency was about mediocre. While lying on a hammock in the sun room, I controlled the EVScope and slewed it from one target to another, checking its progress on my phone. You just can't beat that convenience. When there's a lot of light pollution - as in DC - I quickly notice a brightening at the edges of the screen when taking EVScope exposures that are more than a few minutes long. No such trouble here in Lewes, where the light pollution is not comparable to what it's like in DC. I realized things were different right away, with this exposure of the Whirlpool Galaxy. I've written this before, but wow what a thrill to set up a suitcase-sized telescope and, within minutes, observe nebulae in a galaxy 30 million light years away! The more I use the EVScope, the more I find myself thinking that telescopes like it represent a huge part of the future of amateur astronomy. Light pollution is unlikely to get much better any time soon, and attempts to reduce future warming by increasing the opacity of the atmosphere are becoming increasingly plausible (this is known as solar geoengineering). Electronically assisted astronomy (EAA) will help observers overcome these obstacles - while giving them views of the distant universe that simply can't be matched with traditional optics (at least not in a portable package). The technology will only get better, and I can imagine telescopes that can switch seamlessly between modes ideal for Solar System and deep space object observation. While the EVScope can deliver impressive views within the biggest cities, it dawned on me last night that it really comes into its own under darker skies. Perhaps it's no surprise that even EAA follows the same principle as traditional astronomy: the darker the sky, the better the view. The EVScope only reduces - enormously - the usually extreme difference between dark-sky and polluted-sky observing. For example, I've been trying to get a good shot of the Dumbbell Nebula for the longest time in Washington, DC, but whenever I tried I ended up with little more than a disappointing blob. But just look at the view after just 10 minutes in Lewes. To me, the level of detail and color is nothing short of phenomenal. And what a thought: the Dumbbell Nebula is illuminated gas released by a red giant star before its collapse into a white dwarf (in this case, the largest white dwarf known to astronomers). This is what our Solar System could look like in six billion years or so. So yes: when it comes to the EVScope, it's hard to beat the views. And it fits in a tiny corner of my car's trunk, tripod and all!

I've written about the EVScope and Electronically Assisted Astronomy (EAA) quite frequently in these pages. I was skeptical at first - partly because my EVScope had a technical problem - and only came around slowly. Only last night did I become an enthusiastic supporter. I stepped out on a warm, breezy night with the EVScope in its backpack. Transparency and seeing were both around average; there was no Moon. When I reached our nearby park, I set up in all of 30 seconds. I decided that my first target would be the Eagle Nebula, which I've never glimpsed through a regular telescope. The galactic core was lost in light pollution over the National Mall - the sky seemed closer to white than black - so I wasn't optimistic. And yet! When the EVScope found its target - in just a few moments - and started gathering light, a multitude of stars snapped into view, and then the nebula. After a couple minutes, light pollution started to cloud the view - I haven't tried to tinker with the settings that could help me resolve that issue, not yet - so I stopped the exposure after eight minutes or so. I was left with this: In the dark, on my phone, it looked spectacular. Look! There are the pillars of creation - star-making factories so memorably imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope - somehow visible from downtown Washington, DC, just nine or so minutes after setting up in an urban park. This image does it for me - I like my nebulae ghostly and ethereal - but with a little image processing, even more detail pops out (see the picture at the beginning of this post). Now it was on to the Trifid Nebula nearby, it too lost in downtown pollution. Not for long! Again, I'd never seen it with a regular telescope, yet again, it didn't take long to pop into view through the EVScope. This image I like a little less; the unprocessed version doesn't quite bring out the blue. Still, getting this detail so easily in the middle of a city feels nothing short of miraculous. Then it was off to the Ring Nebula which, of course, never fails to impress - albeit in very different ways through an optical versus an EAA telescope. Whether because of a software update or an unusually transparent sky - I suspect the former - I was, for the first time, able to see the white dwarf at the heart of the nebula. Seeing that would require an enormous regular telescope - too big for my car - and a very dark sky. Imagine my wonder at glimpsing the dead star from the city: our Sun's future, six or seven billion years from now. I didn't have much time left, but I wanted to see how far I could reach. I turned to NGC 5907, a galaxy marginally larger than our own, around 54 million light years distant. I could only take a short exposure - I really did have to leave - but there: an edge-on spiral galaxy that I would never have been able to observe even with my TEC 140. The light in this picture left its source not only after the dinosaurs went extinct. What a thought!

I packed up just as quickly as I set up, and then a pleasant walk home with my backpack. It is simply remarkable to see so much so easily. I've often seen the EVScope's hardware discussed and praised, yet what really stands out to me is the software. If only other mounts, carrying regular telescopes, were so easy to use. I've written it before, but wow: Washington, DC is such a feast or famine city for amateur astronomy. We've had bad seeing on just about every clear night (and there haven't been many) for around five months now. At last, this month, the clouds parted - but on night after night, the seeing remained poor at best. I took out the Takahashi FC-100DZ twice, and both times found the seeing well below average. Both times the Moon failed to impress as it otherwise might, and stars shimmered and danced in the eyepiece. Mars had long since set; I won't have another good look at the planet until 2022. At last, at 4:30 AM on Wednesday morning I stepped out with my EVScope and found the seeing to be . . . okay? It was windy near the ground, to my great frustration, but the stars scarcely twinkled and the internet confirmed it: seeing, it seemed, was about average. Of course that doesn't matter as much as transparency when you want to observe most deep space objects, but transparency was average, too. The sky, in other words, was about as good as it's gotten since autumn. It was a little cold, however, and muddy where I set up in the park. I hoped to test the EVscope on the Ring Nebula and the Hercules cluster: two objects I admired last year with my refractors. The scope aligned itself within seconds - why can't other mounts do this? - and I soon found it to be in perfect collimation. Moments later, it had found the Ring Nebula and I began a short exposure. As I wrote last year, under urban skies the Ring Nebula looks like a ghostly grey ring with a fine four-inch refractor - a ring you can just, just make out with direct vision. Using the APM 140 with averted vision, the ring was plainly obvious. In darker skies, with a four-inch Takahashi, the ring was equally obvious and appeared a little flattened. Every time I looked, there was a visceral thrill to seeing it, with just a couple lenses between my eye and the nebula. Yet through the eyepiece, the object itself was a subtle pleasure. The experience couldn't be more different with the EVScope. That thrill of seeing something with your own eyes is just about gone. Unlike others, I really don't like looking through the scope's eyepiece; it's like looking down a barrel, for one, and at the bottom of that barrel it's clear that you're seeing a screen. Maybe I've been spoiled by fine refractors and fine eyepieces, but it's a letdown. So I look at my phone, and for the most part I wait. The experience of observing - of learning how to see - is completely lost with the EVScope. Yet the thrill of seeing deep space objects otherwise barely visible from the city beginning to resemble their true selves is simply something you can't get with a traditional telescope under an urban sky. This time I really was floored when the nebula almost immediately turned green on my screen, and then when its perimeter began to seem orange, and then when its interior started to take on a greenish hue. The breeze pushed on the tube just enough to blur some of the stars, but what a wonder. Observing the Hercules cluster was a slightly different story. The cluster is always a highlight for me, not least because it's three times older than Earth - or because we beamed a message there from Arecibo, in 1974. With one of my refractors, it looks like a smudge at first from downtown DC, but after a while the stars come out, like diamond dust on a velvet background. It's subtle - exceptionally so with one of my smaller scopes - but magical nonetheless.

Again, the experience couldn't be more different with the EVScope. Hundreds of stars are easily visible, but of course they're slightly bloated; they lack that crushed gemstone beauty that you get with a fine refractor. Many of the stars are also clearly red, a testament to their age: again, things are visible through the EVScope that just aren't accessible with a regular telescope. Is the view more impressive? Maybe not to an experienced observer, but it's different, and that's a good thing. Some complain that the EVScope delivers the same experience you might get with a much cheaper (and more unwieldy) astrophotography setup. That's just not true. The EVScope is marvelously portable, and I can set it up in about one minute. It needs virtually no time to cool down. It's a joy to use and on most nights there's no fuss at all. In half an hour I can pack up - this takes another minute - having observed at least three deep space wonders as I otherwise never could. The key point is that the EVScope delivers a fundamentally different experience than you'd get with either a traditional telescope or an astrophotography setup - and again, I view that as a very good thing. This weekend, we travelled to the Shenandoah Mountains with our "bubble family" for a much-needed getaway from Washington, DC. It took a little negotiation - even a short trip with kids requires a lot of luggage - but I eventually received authorization to stow a telescope in the trunk. There wasn't much room, so the telescope had to be small, and that left two options: the TV 85 or the Takahashi FC-100DC. I decided I wanted the extra reach of the Takahashi, so I unscrewed its focal extender - shortening and lightening it - and then found a way to make it fit with my lightest tripod. To my delight, our cottage turned out to have two balconies, both isolated from surrounding houses, and was just enough of a clearing in the trees to reveal a part of the night sky. That part, I soon realized, could not have been better placed: it would reveal the Ring Nebula and the Hercules Globular Cluster in the evening, and the Andromeda and Triangulum galaxies in the morning. Even better: the forecast called for clear skies on both nights we were there. What are the odds? On the first night, I stepped directly from my bedroom to the cottage's narrow, second-floor balcony. The air was alive with the squawking of birds and the buzzing of bugs. Luckily I brought plenty of mosquito repellant - although it was hard to forget about the legions of spiders spinning webs just overhead - and wow: what a night sky! Bortle 4, by one classification scheme; yellow or maybe green by another. It was, admittedly, not perfectly dark, but to this city slicker it was nothing short of a revelation. It's been so long since I've seen the Milky Way - but there it was, clearly visible. There were in fact so many stars that it was hard, for a moment, to pick out the constellations! Oh, what I've been missing in DC. To my surprise, Jupiter and Saturn both turned out to be high enough to view from the upstairs balcony. Saturn was beautiful, but I've had better views from the city. Jupiter, by contrast, was so clear and full of contrast - and, lucky me, I had tuned in just on time to see another shadow transit! To think that I'd never seen one before this month. Callisto, it turned out, had just finished traversing the planet, and its shadow was still in the clouds. The shadow seemed a bit more distinct - a bit more clearly round - than it had been on the surface of Jupiter with the APM 140 on the 10th, but I found I couldn't increase the magnification beyond 123x without the view breaking down. To my surprise, I also found that a new Delos 6mm eyepiece presented a clearly better view than my trusty Nagler 3-6mm zoom. Next, it was off to deep space. It has literally been decades since I had a telescope under a reasonably dark sky, and so it was such a pleasure to simply trawl through the Milky Way at low magnification, admiring the knots and clusters of random stars. Every patch of the galaxy, every view, resembled an open cluster from urban skies. Incredible. There are, I realized, deep space objects that look better under dark skies - that is, more of the same - and those that look different. The Ring Nebula, I realized when I finally look that way, mostly looks better. I could easily make out a ring without using averted vision, which I can't do with anything smaller than the APM 140 in DC. Yet I could also make out subtle nebulosity within the ring - a first for me - and the ring didn't look quite as round as it seems in the city. The Hercules Cluster, however, looked completely different: less a fuzzy ball and more an explosion of innumerable stars, textured and complex right down towards the center of the cluster. When I saw textured, I mean it was almost as though someone had sprinkled especially dense clumps of glitter haphazardly over a page already covered with a thinner dusting. An unforgettable sight. On the following night, I decided to sneak out in the morning, this time on the bigger, first-floor balcony so I could see more of the sky. I never have much time with how little my son sleeps, but I hoped to get a good view of two huge deep space objects whose surface brightness is just too low for urban skies - the Andromeda and Triangulum galaxies - before catching a glimpse of Mars.

Andromeda was impressive: a bright, fuzzy nucleus (of course) and a subtle but immense disk, stretching out of view even at 25x. I thought that maybe - just maybe - I could make out a dust lane after around 15 minutes of peering, but that might have been my imagination. At last I tore myself away from the view and started scanning for the Triangulum Galaxy, which I've never managed to spot before. After about 15 minutes I tracked it down, and wow - was it ever subtle. I could make out its pinwheel shape using averted vision, and that was incredibly special to me. At last, Mars became impossible to ignore. Snapping in the 6mm Delos I was treated to an absolutely spectacular view of the planet at 123x, featuring that southern ice cap, of course, surrounded by a ring of remarkably dark dunes, and the unmistakable peninsula of Syrtis Major Planum. I have never had such a detailed view of Syrtis Major, and what timing: the Perseverance rover will soon blast off to land at Jezero crater on the border of the region. To be honest, this view alone exceeded my wildest hopes for the Mars opposition of 2020. Amazing to think that the planet will only seem bigger over the next few months! Yet just as on the previous night, although the view was full of contrast at 123x it broke down when I pushed the magnification much further. I had high hopes for 185x with the Nagler Zoom, but no dice. After a while, it was time to pack up. I was sorely tempted to look at the Pleiades, then just wheeling into view, but I had to be ready in case my son woke up. I couldn't complain, of course; together, both nights were nothing short of unforgettable. I now know: there's nothing better than a fine telescope under dark skies. With regards to the rest of my setup, I was really impressed with a new purchase: that 6mm Delos eyepiece. Beautiful contrast, incredibly easy on the eyes, and a nice field of view. The 30mm TeleVue Plössl was less impressive - actually, it's long been my least favorite eyepiece in my Plössl collection. Stars seem a little stretched out away from the center of the eyepiece; at first, it's like they're not quite in focus, and then, towards the edge of the view, they stretch out into miniature arcs. I think I might need another kind of eyepiece for beautiful wide-field views under dark skies. All in all, a memorable trip, and a welcome relief from these COVID times. It's been quite a stretch of clear nights in these parts - as I wrote before, DC is a feast-or-famine city for amateur astronomers - and I've been determined to take full advantage. Last night, I hauled my APM 140 out the door for what I hoped would be an hour of deep space urban observing. As I embarked on the 15-minute walk to the park with, what, sixty pounds worth of equipment, I fretted about a fleet of clouds flitting by overhead. When I got to the park, however, the clouds had largely passed, and although I was drenched with sweat after all that hauling I was more or less ready to go. I was curious to see what the APM could do with no Moon in the sky. The first thing I noticed is that transparency wasn't great, but also that stars were pinpoints almost immediately. Although the difference in temperature from inside to outside wasn't great, I was still impressed that the telescope acclimated just about instantly. The Ring Nebula is almost comically easy to find these days, so I started with it. I could see a clear ring with no averted vision - always nice - but I can't say the view was much brighter then it had been a few days back, when the Moon was out. Still, a nice way to start the night. Next, I tried to track down some globular clusters in Scorpio, then rising out of the worst of the city's light pollution to the south. The double star Al Niyat was a gorgeous sight, but the globulars - M4 and M80 - were underwhelming. I abandoned the effort and switched to simply admiring some bright stars for a while, beginning with Antares. This, to my mind, is a principal difference between refractors and other kinds of telescopes. Stars look so much more beautiful - more natural - through refractors, in a way that's hard to explain. It's something, I think, about the size and color of the "disk." I decided to see if I couldn't track down the Whirlpool and Pinwheel galaxies around the Big Dipper. After spending about five minutes in futility, it suddenly dawned on me that the year was far enough along for Jupiter and Saturn to be rising in the evening sky. Sure enough, when I moved out of the shadow of a tree there they were, high enough already to observe. I didn't expect too much; they were still quite close to the horizon, after all. But when I turned to Jupiter I just about fell off my stool. There, on the limb of the planet, was the pitch-black shadow of a Galilean moon. And there, framed by Jupiter's North Equatorial Belt, was the moon: Europa, if I'm not mistaken. Suddenly the seeing stabilized, and wow: I've never seen so much detail and color on the planet. It was like viewing a Hubble image, at a little distance, while squinting ever so slightly. The Galilean moons were actual disks, not just points of light, though I couldn't see their color, let alone any albedo features on their surfaces. The seeing, I judged, was good but not great. But the telescope! What a thrill to observe the planet with a nearly six-inch refractor. When I turned to Saturn, I was nearly as impressed. The planet just had such a satisfying color through the big refractor: a creamy, buttery pale yellow, with mottled bands of grey cloud. Again, there was a space telescope - or maybe space probe - kind of feel to the image, a three-dimensionality and intricacy of detail that I've rarely seen before. I swung back to Jupiter. As I watched, Europa's shadow vanished in the limb of the planet, and the moon itself started to edge into black space. Then, the Great Red Spot rotated into view - and above it, on the northern hemisphere of the planet, an even darker mass of clouds. When the atmosphere really settled down, every cloud belt and zone was just absolutely full of delicate detail. What a thrill. I could have stayed for so much longer, but I knew it would be just four or five hours before my toddler woke up, and I had to get what little sleep I could salvage. What a memorable night! I've always wanted to be able to see real change on Jupiter - to observe the true dynamism of the inconstant planet. Finally, I had the chance to see the best the planet has to offer in real-time. I can't imagine any of my other telescopes would have shown me as much; the Takahashi might have come close, but not with so much color. I never imagined I'd be able to use such a big refractor before having a backyard. As I lugged the telescope back home, I couldn't stop thinking: it's so worth it for even one special hour with the giant planets. Rocking a fussy baby is a dangerous thing. The mind latches on to anything that can distract from the crying, and for me that means telescopes. Could I really use my Mewlon 180, I wondered lately? The telescope is beautiful, but it takes at least an hour to cool down - about as long as I often have to observe. And would I really feel comfortable collimating it in a park? Could I even haul it to a park in the handsome but bulky carrying case I bought for it? The answer to all these questions, I ultimately decided, was no. At the same time, I happened across a new telescope model: a 140mm refractor made by a German company, APM. At just under 20 pounds, this telescope is remarkably lightweight for a 5.5" refractor, and because it's a doublet - meaning it has two lenses - it cools downs quickly. Color correction is also excellent - maybe not quite as good as my Takahashi FC100, but on par with my TV 85 - and a sliding dew shield means the whole assembly is quite compact. Quality control is so good that the telescopes can ship with strehl reports, meaning you know exactly what effect unavoidable wavefront aberrations will have on image quality. The price, meanwhile, is unbeatable for a big apochromatic refractor. I couldn't help but think that the APM would work much better for me than my Mewlon, especially as I've gotten used to those pinpoint refractor stars. Once the idea was in my head, as usual, I couldn't shake it. I sold my Mewlon and a few eyepieces - including my cherished Ethos - then bought a rarely used, second-hand APM with an unusually high strehl of 0.958. To my surprise, the big telescope rides quite easily on my AYO II mount. I had been told that the mount can't quite handle refractors with similar apertures, such as the TEC 140. But if I balance the refractor just right, it does fine - provided I don't use a heavy eyepiece. Which, hey, I had to sell to buy the telescope anyway. Although I promised myself after June 9th that I'd only take a telescope out in the early morning if the seeing seemed above average, by July 1st I couldn't wait any longer. Both seeing and transparency promised to be below average on the morning of the 2nd, but the sky was clear and I wanted to test the refractor. I went to bed at 10:30 PM, woke up at 2:30 AM, and was out the door at 3:05. I'd bought a large soft case to haul the telescope and all my equipment except my mount, and it certainly made it much easier to walk the 15 or so minutes to my new favorite observing site. When I got there, however, my arm was nevertheless ready to fall off. This urban observing location is really special: screened by bushes in a large park that I have permission to use at night. As on the 9th, I was surrounded by rabbits and fireflies, and by 4 AM a cacophony of birds started calling all around me. The nearby trees are alive with noise - not bird calls, but animals moving through them. An army of squirrels? A flock of pterodactyls? Either way, it's a memorable experience being out there in the early morning. Turning to Mars, the image was clearly brighter than what I observed through the FC-100DC on June 9th, but also softer with a bit more light scatter. Nevertheless, that southern polar cap and some delicate dark albedo features were clearly visible. Switching to Jupiter and Saturn, it was clear that poor seeing and to a lesser extent transparency, not the optics of my telescope, would limit my morning views. Both planets had more color than they do through my Takahashi, and I could see a whole family of moons around Saturn - always a thrill. Even at high magnifications, the view remained bright - another step up over the Takahashi. Yet I couldn't really push past 100x and still see detail; the seeing was just not good enough. Still, the great red spot was as obvious as I've ever seen it. I wanted to have a look at the Ring Nebula to compare the light gathering capacity of the APM to my other refractors. With so much light pollution in the muggy sky, the nebula still seemed faint. But I could clearly make out a ring without using averted vision - a first for me. Then, at around 4:15 AM, I noticed a bright light on the eastern horizon. Was it a plane? Or could it be Venus? I had a look, and yes - there it was, a delicate golden crescent. I've never seen Venus look so beautiful; a mesmerizing sight that defied all my iPhone attempts to take a picture. Walking back was another huge chore, and when I returned I noticed that the wheels on my case already had some wear and tear. Still, I thought the telescope acquitted itself very well. The only false color I detected, I think, was a function of seeing. Stars were, of course, pinpoints. The view was noticeably brighter than it is through my Vixen - about as bright as it was through my dearly departed C8, I figured. Thermal acclimation was nearly instantaneous. The mount was sturdy, with vibrations at well under two seconds. This telescope is a keeper. On the evening of the 2nd, I realized that the sky would be clear again on the morning of the 3rd - except now the seeing and transparency promised to be average. Could I really function for a second day on four hours of interrupted sleep? Yes, I decided I could - and there I was again, in the park by 3:30 AM. This time I brought my Takahashi. I didn't have the energy to lug out my APM on so little sleep, and I wanted to compare the view through the FC-100DC with what I'd had with the APM. Mars was, once again, my first target. I had been a little disappointed with the view of Mars through the APM, although to be honest I would have been blown away had it not been for that magical morning on June 9th. Now, using the Takahashi again, I realized that the view on the 9th was a function of good seeing and good transparency - and a great little telescope, of course. The view on the morning of July 3rd was similar to what I'd had using the APM on the 2nd, albeit less bright and with a bit less scatter (possibly owing to better seeing). The south polar cap was easily visible, and some dark albedo features too - a fine view, but not comparable to what I saw on the 9th. When I turned the telescope south to Jupiter and Saturn, I was surprised: the seeing in that part of the sky was actually worse than it had been on the previous morning. Jupiter in particular was a hot mess, with nothing visible aside from the most obvious belts and zones. I could just make out the Cassini Division on Saturn, and I actually got some half-decent iPhone photos. Saturn photographs much better than the other planets largely because it's fainter. My phone washes out all detail on brilliant objects on a black background, so Jupiter especially almost always comes out as a bright white ball - except in those especially blurry moments, while taking a video, in which the picture just passes into or out of focus. In general, views of Jupiter and Saturn were worse using the Takahashi than they had been with the APM, but a lot of that comes down to a slight difference in seeing. I would say that, with the focal extender, the Takashi probably gives slightly sharper but less colorful and somewhat dimmer views. With that said, the difference in brightness on the planets was less than I expected; the Takahashi puts up a hell of a fight against any telescope, it seems.

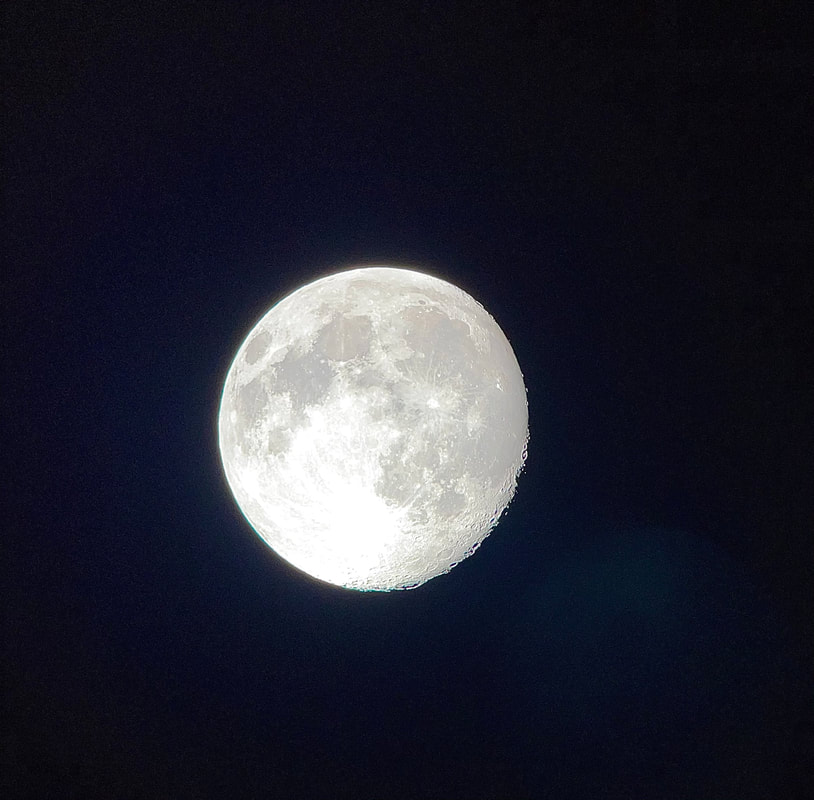

Turning to the Ring Nebula, the picture was very different. In subpar transparency - the forecast lied - the nebula was only barely perceptible at all. I needed averted vision to see a ring, and then again - just barely. I guessed that the view with the APM was twice as bright, a gigantic difference, of course, when it comes to observing deep space objects. Once again, Venus loomed on the horizon when it was time for me to start thinking about packing. Once again, the view was glorious - and the iPhone washed out all details (ditto for Mars). Oh well - I took a shot anyway, and now it's on this website. Somehow, even terrible pictures help me remember the wonder. Dodging crowds of rabbits, I made my way home. The lack of sleep hurts, but I'll cherish these early morning memories. And I sure am happy to have another telescope in the fold. Washington is a feast-or-famine city for amateur astronomy. Clouds and bad seeing can endure for weeks - even months - with little relief, and then, suddenly, the weather clears for a week. When that happens, I've learned to take advantage of it - no matter how tired or distracted I may be. So when the sky cleared last week, I was ready. Unfortunately, the first couple nights were marred by bad seeing. But the last two nights may have been my best since I started this hobby, many years ago now. On night one - on the seventh - I hauled my Vixen 115SED to a park about a ten minutes' walk from my home. With its various upgrades and attachments - including the diagonal - the Vixen weighs just under 15 pounds. My larger tripod - a Berlebach - weighs around 12 pounds. Everything else probably weighs about as much. Walking ten minutes with all that gear - in three big bags - is about all I can take. But I made it, and after thoroughly dousing myself with mosquito spray, I walked towards the center of the park. There, I found a depression screened with bushes: quite possibly the best observing site I've encountered in a city. As I unpacked, I found I was surrounded by rabbits. Over the next two hours, they would routinely hop by, some no more than six feet away. I could see the flash of their white tails bounding along from time to time. My attention, however, was elsewhere. The Moon would rise only after I had to walk home, which meant that conditions were ideal for deep space observing. Of course, while seeing was pretty good, transparency was much worse, and at the beginning of the evening banks of high-altitude clouds seemed to obscure exactly what I most wanted to observe. Still, even then I had a good look at some particularly beautiful and bright stars: Arcturus, for example, glowing like an ember in the dark. Whenever I take out the Vixen - okay, it's been just three times now - I'm impressed by how comfortable it feels to use. The size and weight seem just right to me. Stars meanwhile are absolute pinpoints, and the colors are just sublime. I'm convinced that a fine refractor will spoil every other telescope for the observer. There's just something about the sharpness and color that you can't get with another instrument - even if those other instruments lend themselves to much larger apertures. Anyway, tonight I wanted to observe some globular clusters. I started with M13, the Great Globular Cluster in Hercules. Every nebula, galaxy, and globular cluster aside from the Orion Nebula is a subtle find in DC's light polluted skies. Even the brightest require averted vision to see clearly, and the Hercules globular is no exception. Yet with averted vision, I could make out countless tiny stars: diamond fragments against black velvet. Next, I hunted down M80 and M92: two relatively bright globulars swimming in the most light-polluted part of the sky. They were not immediately spectacular, but then, of course, you think about it: the light coming through the eyepiece left its source during the onset of the Last Glacial Maximum (colloquially called the last "ice age"). There's something indescribably special about scouring the most distant reaches of the Milky Way. And these two globulars I had never observed before. The Ring Nebula (M 57) was last on my list. It was a remarkably easy find, and quite obvious despite its relatively low elevation above the horizon. I needed averted vision to clearly see the ring, and I just wonder what it would look like in a truly dark sky. Still, it's always surreal to see M57: a preview of the eventual fate of our Sun. I went to bed content on the seventh, then woke up on the 8th to realize that seeing and transparency early in the morning of the ninth would both be above average. I can't remember the last time that happened. With Jupiter, Saturn, Mars, and the Moon all slated to be in the night sky, I couldn't miss it. I set my alarm to 3:30 AM - then woke up at 2:30, exhausted but ready to go. I packed up my FC-100DC and walked out the door. This time I nearly blundered into a deer while entering the park. For some reason, that deer just wasn't interested in moving. I was again surrounded by rabbits and this time, a chorus of singing birds. It was beautiful. There were the planets and the Moon, all lined up - and there were high-altitude clouds, defying the weather forecast. For the next two hours, I switched from one world to the next, dodging the clouds as best I could. Here I find it hard to put in words the thrill I got when I turned the Takahashi to Mars. Mars is still many months removed from its biannual opposition - its closest approach to Earth in its long orbit - but the view through the Takahashi was so much better than anything I'd seen before that it truly was like I was seeing the planet for the first time. As you can read in this blog, in previous attempts to observe Mars I always wondered whether I could really make out its surface features. No such confusion this time. There was the south polar cap, bright and clear as day . . . and there were its dark albedo features, not only obvious but intricate in detail, despite the relatively small apparent size of the planet. I was flabbergasted. With focal extender screwed in - and even without - the Takahashi is a stunning planetary telescope. I realized just how stunning when I turned to Jupiter. At around 200x, I have simply never seen so much on the giant planet. You had the feeling that, if only you could get a little closer, you could see an almost Hubble-like level of detail. The seeing didn't quite let me do that, nor did those awful clouds. But still: it was stunning to see all those cloud features I'd previously seen only online or in books. Totally obvious - of course - was the great red spot, and over an hour I followed along as it moved toward the limb of the planet. The four Galilean moons were all lined up, and I could easily make them out as disks. Saturn was equally spectacular, of course. At around 250x, the view was a little dim with those clouds rolling in, but impressively detailed. It was not quite the best view of Saturn that I've had with the Takahashi - owing, I think, to those clouds - but it was close. Cloud features were plainly evident, as was the shadow of the planet on the rings - always a highlight for me. The Cassini Division clearly surrounded the entire planet. Not to be outdone, the Moon was just as impressive as the bigger, more distant worlds. The pictures didn't quite turn out as I'd hoped, but wow: the detail was perhaps even more spectacular than it was on May 31st, and this time without any false color at all. I observed at around 250x for a while, savoring the view especially with TeleVue Plössl eyepieces attached to a 2.5x PowerMate. Crater peaks and rilles in particular were breathtaking to resolve and follow.

I had one quick look at the Ring Nebula before the Sun came up. Although its constellation - Lyra - was now much higher in the sky than it had been on the 7th, the brilliant Moon made up for it by washing out fainter objects. The nebula was quite easy to make out, but dimmer - slightly - than it had been through the Vixen. Now the Sun was coming out, and I had to rush home for my young son's wakeup time. Having had just two hours of sleep, it would be a long day. But so worth it after such a memorable night. So I may have contracted a mild case of aperture fever. Not the first time, and likely not the last. I caught a glimpse of the Ring Nebula with my 100mm Takahashi recently, and part of me was impressed. With averted vision I could just make out a ghostly grey smoke ring - not bad, considering the bright urban sky. Yet the view made me wonder what it might look like through something bigger; viewing the moon made me wish for even higher magnifications and just a bit more light. I like my C8, but its optical quality isn't quite on par with that of my fine refractors. And while it cools down in 40 minutes or so if the weather is mild, that won't cut it in the winter. So, I bought a Takahashi Mewlon 180. It turned out that I had a lot more money squirreled away in my university accounts than I expected, and I can only spend it on research or research-related equipment. That meant telescopes, and the Mewlon, I felt, would fulfill all my needs. It squeezes a lot of aperture into a package that's almost as small as a Catadioptric, except it's a Dall-Kirkham reflector, which means it doesn't have a corrector at the front and therefore cools down quite quickly. It's also a Takahashi, and that all but guarantees excellent optical quality and superior craftsmanship. I was tempted to get the (even) pricier 210mm version, but after a lot of reading I decided on something just a bit smaller: something that would cool down even faster and be less sensitive to poor atmospheric seeing. When you take it out of the box(es), the Mewlon does not disappoint. It's the most beautiful telescope I've ever owned. It looks like a jet engine. It's a bit bigger than I expected - of course - but light and wonderfully well-balanced around its slender dovetail. I got a giant and excessively well-added carrying bag for it, which adds significantly to the hassle of lugging it to my observing sites but adds a little peace of mind, too. Within a week of the Mewlon's arrival, the sky was clear and the Moon a beautiful crescent. I carried both the Mewlon and my TV 85 to our observation deck. It was cold, and I used the TeleVue for about 35 minutes while the Mewlon cooled. Once again, the little telescope surprised me. It seems to defy the laws of physics by squeezing so much performance out of such a tiny package. Details on the Moon were simply stunning, and Saturn - despite being low on the horizon, and despite some very mediocre seeing - wasn't bad either. Two things were immediately obvious when I switched to the Mewlon: first, the view was brighter and I could use a lot more magnification, although the Moon was now lower on the horizon and the seeing was worse. Second, my little Berlebach Report tripod and VAMO Traveller mount just couldn't handle the Mewlon like they could the shorter - but slightly wider - C8. The view wobbled, badly. I've already ordered a sturdier tripod (another from Berlebach) and tripod (this time from Stellarvue). Still, I was delighted with the Mewlon. The Moon's terminator was just a bit more detailed, even at relatively low magnifications, than it had been through the TV 85. The view wasn't completely different at those magnifications - a testament to the much smaller TV 85 - but there was definitely more there, and it was crisper than it had been through the C8. At high magnifications - magnifications the TV 85 couldn't match - a new world started to emerge. I don't think the Mewlon had fully cooled down, however, despite the wait, and I wish I could have stayed out just a bit longer. Whenever the Moon is up, I try to take pictures using my iPhone 8. That's as close to astrophotography as I hope to get, at least for now. Although iPhone pictures inevitably have far less clarity, vibrance, and sharpness than views through the eyepiece, I am learning how to take better shots. I've given up on the gadgets that some telescope makers sell to mount the phone in front of the eyepiece; in my experience, the results are too often disappointing. Instead, I've learned to hold my hands more steadily - steadily enough to focus the phone on the object I'm observing. I've also learned to enhance the clarity and definition of the photos I take, and then slightly increase the settings for shadows, vibrance, and occasionally black point to better approximate what I'm seeing. My most important lesson, however, is to take videos of anything other than zoomed out views of the Moon. By taking videos, I can freeze on frames in which atmospheric seeing suddenly stabilizes. When I take a screenshot of those frames, the resulting picture is often much sharper than I get by just starting on picture mode. Some objects that are totally washed out otherwise - like Saturn - start to look like themselves when I take a video. I enjoy taking even the decidedly amateurish photos I can get with my iPhone. But at some point, I'd like to try my hand at sketching, like the nineteenth-century observers I've been reading and writing about lately. I doubt my results will equal theirs at first, but it will be fun to try.

|

Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed