|

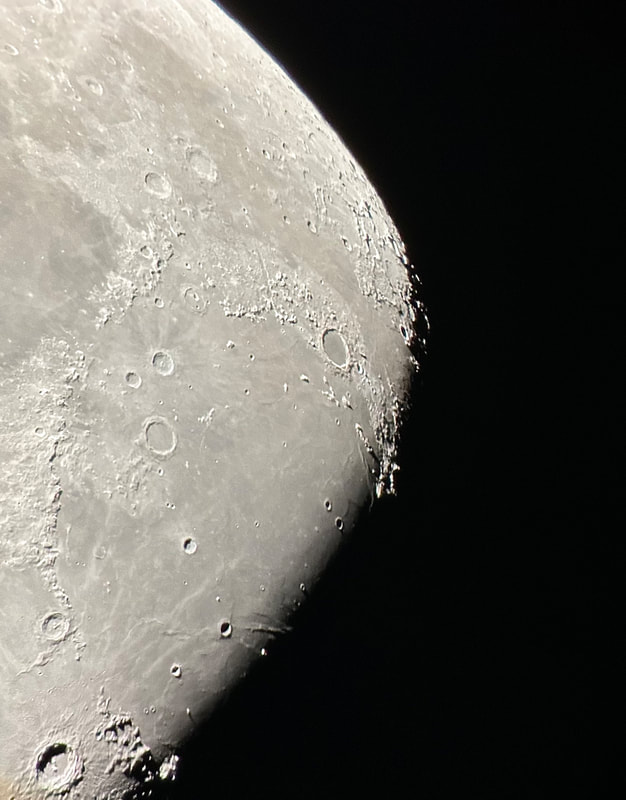

Usually, the atmosphere is turbulent during our DC winters, but this winter has been an exception. The reason might have to do with atmospheric circulation rerouted by a particularly intense El Niño, but I'm not sure. In any case, winter has been unusually accommodating for amateur astronomy in the District. Yet I haven't taken out my telescopes, and I haven't updated this blog, because, unfortunately, I've found myself too sick, too overworked, or - most often - both. This month has been much better, however, and on the 18th I finally decided to give my kids a view of the halfway-illuminated Moon. I stepped out with what is now my smallest refractor - the Takahashi FC-100DZ - and quickly found atmospheric turbulence to be a little worse than average. That's perfectly okay for a DC winter, and after the telescope cooled down - in about ten minutes - it delivered a very nice view of the Moon. Unfortunately, when uploaded to this blog the picture looks a bit blurrier than it does on my desktop. But look closely at the center. That's Rupes Recta, a linear fault about two kilometers wide that cuts across some 110 kilometers of the lunar surface. Here it is zoomed in: Just below the fault are the craters Birt A and B, named after William Radcliff Birt, a nineteenth-century selenographer. Birt coordinated a network of amateur lunar observers across Britain who all sought to record changes in lunar features, which they thought would reveal the Moon to be a world similar to Earth. It's a story that I'll describe in my next book, Ripples on the Cosmic Ocean. The book is one reason I've been so busy this winter: I've finished a complete draft, and am now revising (partly by shortening). In any case, the kids enjoyed the Moon. For them, it's a neat little thing that daddy likes to show off occasionally. Of course, I try to impress them by waxing poetic about the wonder of gazing, from a comfortable little backyard, at the alien peaks and hollows of a whole other world, one utterly different from our own. They're appreciative, but hardly awestruck. I've decided that it's nice that Moongazing is so normal for them. The following night was clear again, but a good deal colder. Still, I decided to try my Mewlon 210. After letting it acclimate for about 90 minutes, I walked over to a nearby tennis court and pointed it at the Moon. Once again, I was struck by just how easy the Mewlon is to handle. It's lightweight, and you hold it by the rock-solid finder scope. It's just a wonderfully-crafted hunk of metal and glass. It's hard not to want to use it, if that makes sense. When I pointed the Mewlon at the Moon - and yes it's so nice not to have to attach and then align the finder scope - I found it was cooled down and well-collimated. Atmospheric seeing was about average, but the view was quite breathtaking. The terminator had advanced a little beyond my favorite spot on the Moon - the expanse between and around Plato and Copernicus - yet both craters retained a hint of shadow around their rims. The Mewlon gave a three-dimensional quality to the extraordinary complexity of the terrain in this part of the Moon, in particular the mountains and crater rims. The iPhone pictures I took suggest some off-center coma distortion, but I noticed nothing while viewing the Moon. I don't know what to make of that. Still, I can report that I stepped inside - hands nearly frozen - thinking that I'd be crazy to ever sell my Mewlon. On the following night - that's the 20th - I sat down to write this blog entry. Then I noticed the Moon, shining through my window. I checked and, lo and behold, seeing was supposed to be better than average - way better than I normally expect in winter. I hesitated, but of course the temptation was too strong. I stepped out with the DZ, because I needed something that cooled down fast. This time the view was truly sublime. With the Moon near zenith and the atmosphere unusually stable, the fully-acclimated DZ showed off what it can do. The view wasn't as bright as the Mewlon offered on the previous night, but owing to the steady atmosphere they were a bit more detailed. I noticed craterlets on Plato's floor with the Mewlon - a classic test of good seeing and optics - but now, with the DZ, they were more continuously obvious.

I soaked in the view for a 30, maybe 45 minutes as my fingers slowly froze. I did notice that the view routinely slipped ever so slightly out of focus, owing perhaps to the focuser with the telescope pointed straight up. But wow, that in-focus view was wonderful: among the best I've had of the Moon. I especially enjoyed the lunar maria. The picture above gives a hint of the delicate tendrils I followed across those maria: subtly different shadings, some radiating from brilliant, intricately-detailed craters. It was a lot to take in, but my fingers soon convinced me to pack up and head inside. Lunar observing is perhaps overlooked in amateur astronomy, but it truly is an incomparable experience to explore another world while standing within sight of home.

2 Comments

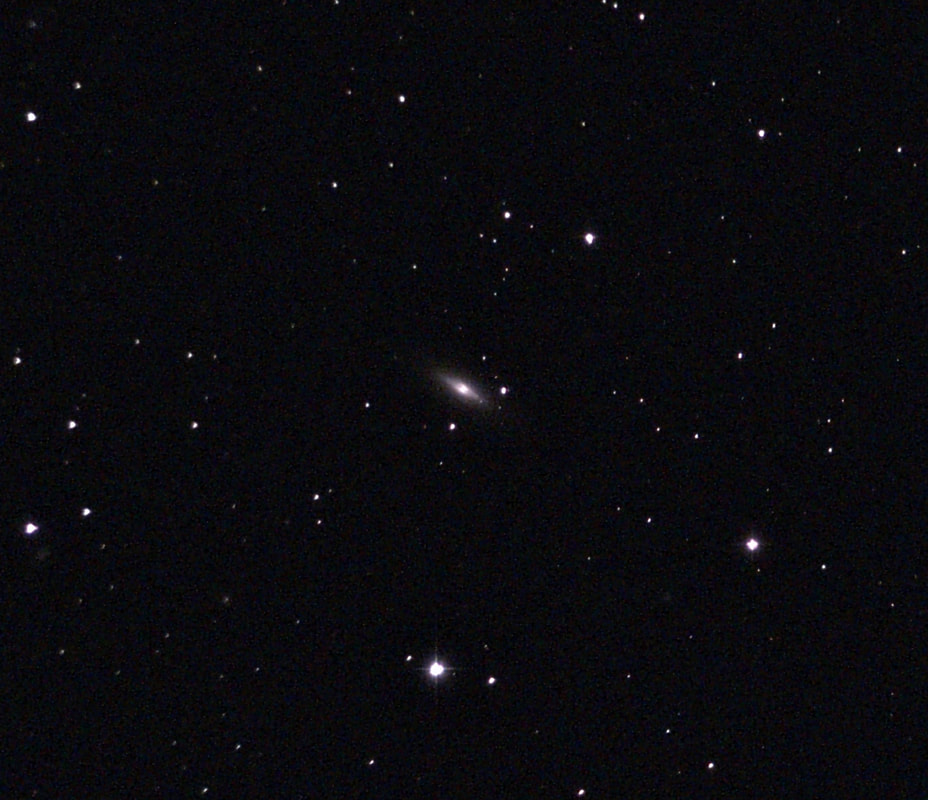

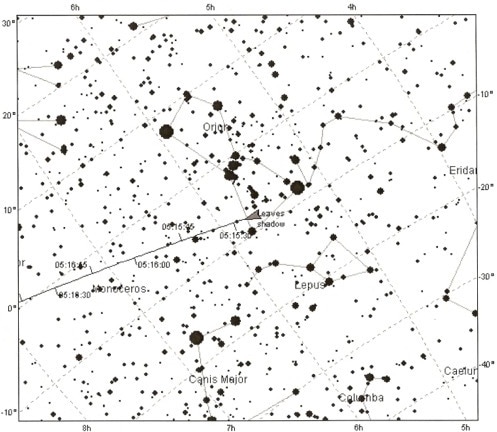

Recently, I've been on a mission to optimize my grab-and-go setup. Slowly but surely, parks that offered dark corners for a telescope have been saturated with bright lights: the kind that needlessly waste energy, confuse nocturnal animals, and pollute the night sky. I have to walk further than I have before, or settle for less than ideal observing conditions. To that end, setups that used to feel perfectly mobile now are discouragingly cumbersome to use. I admit I was tempted to swap my FC-100DZ for a lighter telescope, such as the FC-100DC I used to have and love. Then I had an epiphany - one I should have had long ago. With its diagonal removed and dew shield retracted, the DZ is just over two feet long. Couldn't I find a padded bag that long? If so, the DZ would be as easy to transport as my dearly departed TV 85, while offering considerably better performance. I found the bag - for just $23! - and wow: what a difference. It's strange but true: the DZ is as transportable as much smaller telescopes, but offers truly stunning views of everything that shines through light-polluted skies. The other night, I pointed it at Saturn, which is just now reaching opposition (its closest annual approach to Earth). The view was spellbinding, with glimpses of detail in the planet's clouds that were among the finest I've seen. On the other hand, DC's summer mosquitoes did not give me a moment's rest, and I was grateful that my little setup takes just a few minutes to disassemble. Then, last weekend, it was off for what has become an annual trip to the beach near Lewes, Delaware. I brought my EVScope 2, eagerly anticipating darker skies. Unfortunately, I soon found that atmospheric transparency was lower near the beach than it has been in years past - owing, once again, to that wildfire smoke. Worse, my recent experience with a truly pristine sky in Manitoba left me unimpressed with the view in Delaware. Sure, the Milky Way was barely, and I mean just barely, visible after fifteen minutes outside in the dark. But there was simply no comparison. I occasionally fantasize about selling my EVScope in exchange for a more capable astrophotography setup. The three (!) clear nights I experienced in Lewes reminded me why I have that fantasy - and why I haven't acted on it yet. First, the telescope needed collimation. If you've read any reviews of the EVScope, you'll know that some complain about the need to collimate such an expensive gizmo. Let me assure you that it's much easier than collimating an SCT, for example. Even when the telescope is badly misaligned - as it was for me in Lewes - the entire process takes a few minutes at most. The real problem is that Unistellar's instructions include a glaring error. To collimate the telescope, it should not be pointed at a particularly bright star - I tried Antares - because the star's brilliance will not allow you to see the secondary mirror when out of focus. I suppose it's a minor detail, but this little mistake can create a lot of frustration. Usually, it takes just moments to align the EVScope and get it ready to slew to any object you can imagine. Usually. On one night in Lewes, I had to turn off the telescope a couple times before it aligned itself. On two other nights, it did not precisely center objects after finding them - so that, at the telescope's highest magnifications, objects were simply offscreen. On a third night, everything worked seamlessly. I carefully leveled the telescope, collimated it, and waited over thirty minutes for it to acclimate. That may not sound arduous to veteran amateur astronomers - but it's hardly ideal for a grab-and-go setup. When the telescope is aligned, it tracks objects seamlessly. The trouble is that its altazimuth mount cannot perfectly track stars on long exposures. This isn't visible while peering into the eyepiece, but it does show up clearly in astrophotographs taken with the telescope. Since most people will use the telescope by staring at their phones or tablets - in fact, some Unistellar models don't even have eyepieces - this is a serious limitation. Even this six-minute exposure of the Eagle Nebula has distorted stars. Stars are also distorted - even through the eyepiece - because stars shimmer in all but the steadiest atmospheric conditions. When using a traditional telescope - especially a refractor - you may see a roving, flickering pinpoint. Yet the EVScope takes exposures to provide its bright views of deep space objects, and in these exposures the undulating pinpoints that are stars in mediocre seeing all congeal into blurry blobs. For a refractor aficionado like myself, the effect is deeply unsatisfying. To me, it really does not feel like you are actually peering into space when you use an EVScope. Occasionally I wonder: what am I getting here that I could not obtain by finding images on the internet? Have a look at this shot of the Wild Duck Cluster, for example. The problem is compounded by the reality that Unistellar's software cannot quite compensate for the effects of light pollution. Overall, it does a remarkable job - I'm still amazed that I can admire the Triangulum Galaxy from downtown DC, for example - but there's still a good deal of noise even under a Bortle 4 or 4.5 sky (as in Lewes). Have a look at this 24-minute exposure of the Pinwheel Galaxy, and notice the noise. Another inconvenient truth is that, even with the galactic core above the horizon in the summer, there just aren't that many objects that truly impress when viewed with the EVScope. You have to remember that although the EVScope allows you to view galaxies and nebulae that are far beyond the reach of a comparably-sized traditional telescope, it is also incapable of providing satisfactory views of many objects that such a telescope would reveal. Open clusters, double stars, the Moon, and the planets: everything that impresses when seen through a telescope like the Takahashi FC-100DZ is underwhelming at best when viewed with the EVScope. In practice, dozens of objects in the EVScope's catalogue look like this, and hundreds are far less impressive. The EVScope also seems to have a weak wifi signal. Walk twenty feet away, and you're likely to lose it. You can forget about sitting indoors while operating the telescope. That's too bad, because mosquitoes really can make it hard to stay outside in our muggy summers. In other places, winters are just too cold for comfortable observing. Wouldn't it be easy for Unistellar to include some way of amplifying the wifi signal on its $5,000 device? So yes, I was getting a little annoyed in Lewes. I kept imagining what my TEC 140 might reveal; not nebulae in a distant galaxy, sure, but pinpoint stars on a velvety black background, and spectacular planetary views. This is the best that the EVScope can do on Jupiter, even after a recent software update that dramatically improves planetary performance. I admit: I could go on. Suffice it to say that my nights in Lewes reminded me that, if you buy an EVScope, you really should go for the EVScope 2. This is because the eyepiece is really a lot better than some reviews suggest. Somehow, images of nebulae and galaxies are much brighter and sharper through the eyepiece than they appear to be when viewed on a phone or tablet. The distortions I complained about above - those blurred stars, in particular - are also minimized when viewed through the eyepiece, likely because the small scale of the image mitigates them. As a result, I am consistently impressed by the nebulae and galaxies I see through the eyepiece; so impressed that I take an image that then disappoints. Just before I took the image of the Pinwheel Galaxy that you've already seen, I invited my wife and our friend outside to have a look. Both are astronomy novices, to put it mildly. Both seemed skeptical that they'd see much. Yet when both craned over the EVScope eyepiece, they gasped. They could not believe that they had seen a whole galaxy across 20 million years in time and space. They kept saying how cool it was. "It's almost like one of those picture slide viewers," my friend eventually said. Indeed. You see so much more - and so much less - than you would with an ordinary telescope. That is why I think I'll keep the EVScope . . . for now. Here are some extra images, showing medium-length exposures of some of the best-known sights in the summer sky. Often, around this time of the year, the unstable atmosphere of winter yields to the more settled air of spring in Washington, DC. With the mosquitoes a month or two away, now is the time to observe as much as possible. The planets are all lined up at sunset, but unfortunately that part of the sky is obscured in all my nearby observing spots. Instead, for two nights over the past week, I've enjoyed a world much nearer our own. Today the sky was a beautiful, deep azure, and tonight's forecast called for good seeing with fair transparency. I decided conditions were good enough to exert a little more effort than usual. I hauled out my TEC 140 - now on a hulking Berlebach Planet tripod - and found a nook not far from my backyard. At this time of the year, budding leaves are just beginning to make my backyard unusable for astronomy. Turning to the Moon, I was disappointed - if not exactly surprised - to realize that the forecast had, again, gotten it wrong. Seeing seemed mediocre at best, and the atmosphere had that soft, milky quality that often frustrates planetary and lunar viewing. As my eyepieces and, to a lesser extent, my telescope cooled down, the atmosphere between me and the Moon started to stabilize - or, rather, it started dip into fleeting moments of clarity. Especially compelling in these "revelation peeps" - using Percival Lowell's terminology, as I've mentioned in an earlier entry - was Schickard crater, the massive walled plain clearly visible towards the center-right of this picture: Schickard's crater floor - that walled plain - was alive with irreducible detail, including countless tiny craterlets. As Eugene Shoemaker established at the dawn of the Space Age, the layering of lunar features provides a roadmap to their age. Signs of bombardment on the floor and walls of a big crater provide clear evidence that the big crater is very old. Of course, the little craters scattered around the big crater would have formed long after the big one. I love looking at the Moon as a geologist might, and I am always especially drawn to features on which observers have reported transient lunar phenomena (TLPs). Influential amateur Patrick Moore, for example, reported what seemed like a mist over Shickard just before Hitler's army invaded Poland in 1939. This time, however, all was crystal-clear. It was not my first lunar experience of the week. Several nights ago, I stepped out with my most portable setup - the Takahashi FC-100DZ on a photographic tripod - because atmospheric conditions were forecast to be mediocre at best. I'm glad I did! After I set up - with only my Baader variable zoom eyepiece in hand - I turned to the Moon and realized that, in fact, seeing was far better than average. Have a look at the picture above. Comparing it to the picture that begins this entry will reveal that, for amateur astronomers, the state of the atmosphere can be so much more important than the capabilities of a telescope. The first image was taken by a telescope that costs well over twice as much, and gathers more than twice as much light, as the one that provided that second image. Yet the second image is clearly far better. Here's a close-up of my favorite stretch of the Moon: the wonderfully diverse landscape winding from Plato (top) and Vallis Alpes down through Mare Imbrium to Archimedes, Erastosthenes, and finally spectacular Copernicus, here largely enveloped in shadow. Many of these features - or environments, as I prefer to think of them - have a rich and often bizarre history. Across some three hundred years, scientists compared them to features on Earth, speculated about their supposed inhabitants, tracked their alleged changes, and finally explored them through the voyages of crewed and robotic spacecraft.

Just look at the extraordinary detail the little Takahashi reveals - and remember that, as usual, this is an iPhone picture that blurs what is visible to the naked eye. Honestly, if you're into lunar exploring, you don't need more than a quality four-inch refractor. Seeing was forecast to be mediocre yesterday, and atmospheric transparency will below average. But the Moon rose exceptionally early - it was high in the sky by early afternoon - and therefore within range of my backyard. It had been a couple months since I was out with a telescope, owing to the turbulent winter atmosphere here in DC. I had to scratch the itch. As usual, I set up my Takahashi FC-100DZ in moments, this time with my CT-20 mount attached to the Berlebach Uni tripod. This was a lightweight but rock-solid setup, and as usual the refractor cooled down in just a few minutes. As the sky darkened to an indigo blue, I wheeled the telescope over to the Moon - and was stunned. Seeing, it turned out, was a good deal better than average - and the Moon was just beautifully sharp through my 24mm Panoptic eyepiece (which gives a magnification of just over 33x). Check it out, now at 80X with a 10mm Delos: Very striking last night was my favorite lunar crater, giant Plato, which as I've discussed in this blog was the focus of efforts to detect lunar environmental changes - and perhaps signs of life - in the nineteenth century. Many contemporary observers sought to measure shifts in the crater rim's shadows, which supposedly betrayed evidence for an atmosphere. Ever since reading their logbooks, these shadows had a special significance for me - and now I always try to see them change. No luck yet! The cluster of tiny (from our perspective) craterlets on Plato's floor are often a test of good seeing and great optics, and I think I could just make out a few of them last night. Then I wheeled over to the mass of giant, craggy craters along the Moon's southern terminator, which always provide a spectacular view. Copernicus, quite possibly the most striking lunar crater, is so impressive when the Moon is around halfway illuminated. Occasionally the atmosphere seemed entirely stable, and when it did the crater snapped into exquisite detail. Copernicus was the target of Eugene Shoemaker's pioneering, 1962 study on lunar stratigraphy, which helped unearth a kind of Rosetta stone for deciphering the history of the Moon's landscapes. Looking at the layers upon layers around the crater, now at 175x, it's easy to see why: Last night was a reminder to be wary of seeing forecasts. As I've experienced before, they can be really inaccurate - and in any case, seeing can vary from part of the sky to another. I'm going to try to avoid staying in on a clear night because bad seeing is forecast; next time that happens, I'm going to have a look for myself.

For amateur astronomers, two things happen to the atmosphere around this time of year in Washington, DC: in general, transparency improves, and seeing - meaning, of course, stability - deteriorates. Daytime brings deep blues, sunset a beautiful gradient from azure to scarlet, and nighttime brilliant winter stars in a velvet tapestry (when not facing towards the National Mall, at least). At the same time, the stars noticeably twinkle far more than they do in summer, and moments of steady seeing become ever rarer. The muggy, mosquito-plagued nights of summer, when the planets can very occasionally look like little Hubble photos viewed from afar, are now a distant memory. All the same, since keeping this blog I've found autumn to be my favorite time to observe. It's just so much more comfortable being outside, the planets are still high in the sky, and my refractors at least give me a puncher's chance of making out some detail on them, even in nights of mediocre seeing. With that in mind, I stepped out on the 14th, Takahashi in hand, and found a nook near my mostly tree-covered backyard that afforded me a good view of Mars. It was cold by DC standards - around freezing - but my telescope was well acclimated and the view was beautifully sharp. The Martian south pole in particular looked large and sort of smeared; not quite as brilliant as it can, but larger in dimensions. Later, a spectacular set of pictures posted by Peter Gorczynski over at CloudyNights.com revealed the cause: a swirl of clouds around the pole that were barely visible to me in the mediocre seeing. I didn't last long in the cold weather, and over the next week seeing here in DC grew worse - but transparency remained better than average. I decided to test out the Unistellar EVScope 2 on the comparatively few but spectacular deep space objects that are beginning to climb high above the horizon in our late autumn sky. On the 22nd, I marched about 20 minutes uphill from my house to my daughter's school. Its field is now the nearest I know that is not completely saturated with light, and I can only hope it stays that way. It's not hard to haul the EVScope that distance, thanks to the relatively ergonomic backpack it comes with, and I can only emphasize yet again how absurdly easy it is to set up the telescope once I'm in position. It takes no more than a minute to have the EVScope fully aligned and tracking my first target. It quickly and easily hooks into its tripod, immediately connects to my phone, and in just moments aligns with the night sky and slews to my first target. It takes me two or three times longer to set up my refractors on their sample manual mounts, which of course don't have any software at all. Other tracking amounts, even the simplest ones (such as the iOptron AZ Mount Pro I own), require far more steps to set up, and often don't quite align perfectly; it's why I inevitably favor manual mounts when stepping out with my refractors. I'm not sure how Unistellar leapfrogged all the established brands in amateur astronomy by offering a mount that truly is plug and play - but they have, and it's wonderful. After I let the telescope cool down, I turned to the Orion Nebula. In the past, I've tended to focus too much on my phone while the telescope slowly integrated its pictures and the view of my target gradually brightened. This time I favored the eyepiece, which as I've written elsewhere is much improved on the EvScope 2. I now noticed that the eyepiece view seemed much sharper and, to my surprise, three-dimensional than the image on my phone. The dark nebula jutting in front of the familiar crescent of the Orion Nebula, for example, truly looked as though it was in the foreground, and I followed a fascinating zigzag pattern of dark nebulosity weaving across the bright core that mostly washed out in the phone image. The EVScope permits easy if relatively low-resolution astrophotography, but the current iteration at least is really designed for observing. I've complained that using the EVScope is a very different experience from using a traditional telescope, because I've tended to wait around for the images to integrate on my phone. This time, I was glued to the eyepiece - and it really did feel like a proper observing experience. The EVScope 2 improves considerably over its predecessor, and the Unistellar software has continually added new capabilities. Just have a look at the image of the Orion Nebula that I took almost exactly two years ago, and compare it with this week's version. I suspect I could further improve the view through the EVScope 2, and I wonder what it would look like were I truly under a dark sky. Still, I find the progress to be really exciting. Just last night, I learned that Unistellar had released yet another software update: this time to enable planetary observation. I couldn't resist, and marched back to the same field. This time, however, I was a little disappointed. While the telescope for the first time automatically dimmed its images of Jupiter and Mars and showed real details on both worlds, overall the view was of course radically different from what I see through my refractors. While traditional telescopes may not as clearly reveal the cloud bands of Jupiter, for example, they show far finer and subtler detail; far more realistic and impressive coloration; and of course the moons and stars surrounding the planets.

I expected as much, but in the moment I couldn't help but be underwhelmed. Yet while walking home, I considered where the technology might be in another two years. Eventually, I suspect there will be few if any areas where traditional telescopes reign supreme. To me, their greatest value could then lie in the connection they provide to generations of observers stretching back to Galileo: to a history of often-eccentric women and men straining at odd hours to discern barely perceptible truths hidden across unimaginable distances in time and space. There are some things clever software can never replace - not many, perhaps, but some. Autumn came early this year in Washington DC, yet the relative warmth of early autumn lingered well past its usual expiration date. The mosquitoes lingered with it, even if their population fell with the leaves, but overall it's been a gorgeous month in the city. Over the past week, we had three crisp, clear nights with tolerably good seeing and transparency. With the canopies above my yard increasingly bare, I was able to peak through and branches and observe without hauling heavy gear for twenty exhausting minutes. A few nights ago, I rolled out my TEC 140 to observe the Moon and Jupiter. Night comes early at this time of the year, of course, so I made it outside before my six-year-old daughter's bedtime. I asked her to join me, and when she did she was thrilled to make out craters on the Moon and, with some difficulty, cloud bands on Jupiter. To my surprise, those were unusually difficult to make out. The sky had a milky quality around bright objects, a kind of watercolor softness, that seemed to obscure detail on the likes of Jupiter. Still, a memorable experience for daughter and daddy alike. On November 8th, conditions promised to be marginally better, and temperatures were just about ideal. This time, I stepped out with a much lighter setup: my Takahashi FC-100DZ, clamped to the CT-20 mount that I'd screwed into my Berlebach Uni tripod. It's a more robust outfit than I take to the local park, but it's still easy to move all in one go. A quick aside: the exceptional weight of the DM-6 mount can make it really sturdy and capable of handling surprisingly hefty telescopes. Yet it also ruins the portability of my TEC 140. The mount feels at least as heavy as the telescope, and when yoked to a tripod it's a chore to move even without the telescope attached. Another problem is that attaching the telescope to the DM-6 mount is a heart-stopping experience in the dark. It's hard to be sure that the dovetail is actually in the clamp, and I've now been unpleasantly surprised several times when the telescope suddenly lurched down after I thought I'd got it in. I live in fear that on some sad night I'll misjudge it, step away, and watch in horror as the telescope crashes to the ground. I have no such problem with the Takahashi. Yet the lightness of the CT-20 mount does mean that the telescope tends to tilt - even when perfectly balanced - if objects are too close to zenith. The CT-20 has an answer, however: it's easy to adjust the tension in the altitude and azimuth axes. This can mean that there's too much tension to easily nudge the telescope along when observing objects that are high up in the sky, but I'll take the tradeoff: less weight and less hassle is worth some compromise. In any case, the Takahashi gave me some very satisfactory views of the waning but still nearly full Moon. The view along the emerging terminator in particular was quite striking, while the Moon's fully illuminated surface showed a mesmerizing swirl of subtle grey shadings. The rays streaking from Tycho, one of the youngest big craters on the lunar surface, are always impressive when the Moon is this close to full. Yet Mars is now wheeling towards its biannual opposition, so of course it stole the show. The planet is quite high in the sky by around 10 PM EST, and it's already brighter than any celestial body visible at that time save Jupiter and the Moon. I feel that its color even by naked eye is not quite as blood-red as it was two years ago; it's paler and a little closer to orange. The Takahashi revealed its waxing globe, but showed considerably less contrast than I could make out a couple years back. In moments of good seeing I could make out the south polar icecap, and then a dark albedo swirl around the ice, interrupted by lighter land before continuing towards the north. Yet the view was anything but sharp, and the planet seemed unsteady somehow in the mediocre seeing. Part of the problem is that much of Mars is currently obscured by bright dust storm: a common if frustrating occurrence when Mars makes a close approach to the Sun. It was to gain a clearer view of the Moon and Mars that I stepped out last night with the TEC 140. Conditions seemed about the same, except it was colder and the reappearance of a halo around the Moon suggested that transparency would be lower. The TEC takes meaningly longer to cool down than the Takahashi, although in both cases the Delos eyepieces take longer to acclimate than the telescopes. I'm not sure it's widely understood that compound eyepieces take longer to cool down than, say, Plossl eyepieces - but that's certainly been my experience, and it does stand to reason. There's just a lot of glass in those things.

In any case, both refractors and their eyepieces need only a few minutes to give acceptable views, even if they do take longer to fully acclimate. When everything was ready I was surprised to find that the TEC 140 actually provided slightly softer views than the Takahashi did the other night, even if contrast on Mars in particular seemed just a bit higher, and the Moon's terminator at times snapped into exquisite if fleeting focus. I was once again impressed by the Takahashi; despite its compact size, I rarely feel I'm missing out when I use that telescope, the way I did with many other small telescopes I've owned. It punches far above it weight. Yet to me the bigger takeaway was that the difference between telescopes is often completely swamped by atmospheric conditions. In mediocre seeing and transparency, there really isn't much of a divide between the $8000 (!) TEC 140 and the $3000 Takahashi (of course both telescopes have world-class optics; even in bad seeing, I would suspect a meaningful difference between them and a run-of-the-mill refractor). In my years of observing here in DC, I can probably count on one hand the nights on which the atmosphere was so stable and clear that I could use magnifications of 200x or more. The pricey difference between optics is often less apparent here than it would be elsewhere, and I think that's something observers should acknowledge more often. Where you live will dictate the gains you get by spending more on bigger and fancier telescopes. William Sheehan - who publishes some of the most engaging books on the history and practice of planetary and lunar observing - writes that as an observer views Mars near opposition, "over it, intermittently, uncertain details dart and then are gone like doubtful visions." None other than Percival Lowell - a key popularizer of the Mars canal theory, among other things - coined the term "revelation peeps" to describe these sudden glimpses of intricate detail. That is precisely what Mars had on offer tonight. It wobbled and wavered, like a coin seen through the burbling water of a fountain. Then, for fractions of a second, it snapped into sharp relief, looking really and truly like a planet seen from an approaching spaceship. Just before my brain could grapple with that new reality, the planet reverted so quickly to an indistinct blob that I could scarcely believe it had ever been otherwise. Mars! Always so difficult, but oh so compelling. Earlier this month, I set forth on a night of above-average seeing to the field that has become my favorite observing spot, just an eight minutes' walk from our new home. I heaved up the hill bordering the field, hauling my Takahashi and an uncomfortably heavy backpack, full of expectations. As I rounded the top of the hill, I saw . . . this. It's one thing to install new lights, but these were about the brightest I've seen in Washington, DC. I could scarcely believe my now not-at-all dark adapted eyes. Another observing spot - my third, since this blog began - ruined by newly installed, fluorescent lighting. It's demoralizing to experience firsthand how every patch of dark sky in the city is steadily being surrounded and at last consumed by unnecessary light. I wandered home, too stunned, too sore, and too tired to find another location to set up. In the days that followed, I reviewed my options. I wandered around my home, and found another location, in a neighborhood garden, just a bit farther than the field - but a lot more overgrown with bushes and trees, and no doubt overrun by summer bugs. Then there was another field, perhaps a 20-minute walk away, and (for now) dark at night. Wherever I went, it would be farther: and I had trouble enough walking the eight minutes to the now unusable field. I decided I had to reduce the weight of my grab-and-go setup, and in particular ease the strain on my shoulders. But how? MY DM-4, I thought, was about the lightest mount I could use with my Takahashi FC-100DZ. I agonized over whether to exchange the telescope for something smaller and less capable. I bought it in the first place because it was the biggest and best telescope - that cooled down quickly and provided spectacular lunar and planetary views - I could easily walk with for 10 or 15 minutes. But 20 minutes? And with the mount I needed, and my eyepieces? Eventually I figured that the step down to something smaller - a Takahashi FC-76 DCU, for example - was just too big a fall to be worthwhile. Since my tripod is already wonderfully light, I was left with my eyepieces and mount. The eyepiece problem was easy to solve. Rather than carry four Delos eyepieces, I decided to take just one eyepiece with me: a Baader Mark IV Variable Zoo. When equipped with its barlow lens, it would give me all the magnification I could want. There was a cost: a marginal loss in sharpness, perhaps, and a meaningful loss in field of view (which means something with a manual mount). Still, I found it a small price to pay compared to the alternative (swapping telescopes). I also started researching mounts. Readers will know I settled on the DM-4 after using an AYO II mount. Both mounts are impressive. The AYO II is lighter than the DM-4 and more compact, even as it seemed less durable. Now I wondered whether to exchange the DM-4 for another AYO II; weight, it seemed to me, had to come first. However, I soon found some intriguing newcomers in the quality manual mount market. One in particular stood out: the CT-20 by NoH's Mount, a little company owned by an independent craftsman in South Korea. On paper, the CT-20 weighed less than half as much as the DM-4 (and a third less than the AYO II), while being more compact than both. It cost less and handled more weight. It seemed almost too good to be true - but I bought it, and sold the DM-4. To my surprise, on the night the CT-20 arrived from South Korea, the sky was clear and both seeing and transparency were well above average. I greedily unpacked the little mount, hoping I'd be able to use it immediately. I was immediately impressed - and, to be honest, a little surprised - to find that its build quality seemed exceptionally high, on par certainly with the AYO II and DM-4. I was also delighted to find that the mount is even more compact than I'd expected (this is a rarity in amateur astronomy, where things tend to be much bigger than you thought they'd be).

This time I packed my mount and eyepiece into a much smaller, more comfortable backpack; all in all, I think I shaved about ten pounds from the load I had to carry. I walked the 20 minutes to the more distant field, and was delighted to find that I still had some energy left - and that the field was mercifully dark. I unpacked, set up, and to my astonishment soon found the mount at least as stable with the Takahashi as the DM-4 - and that without the vibration suppression pads that I used with the bigger mount! It also allowed my telescope to easily clear my tripod; with the DM-4, I'd needed a ($250!) tripod extender for that. I quickly slewed to the Moon, and there encountered another surprise: a stunningly sharp view of the lunar terminator in the best seeing I've experienced all year. The mountains on the lunar terminator in particular took on a gloriously three-dimensional character, and I easily made out countless subtle rilles and scarps. Rupes Recta, the so-called "Straight Wall" of the Moon, was perfectly illuminated and a particularly striking sight. I got a genuine sense - maybe for the first time - of how eighteenth- and nineteenth-century astronomers could have mistaken rectilinear features on the Moon for signs of intelligent life. I'm not sure a Delos eyepiece would have afforded a better view; in fact, I couldn't imagine a better view. Next up was Jupiter, and wow: what a sight. I have never - not even with my TEC 140 - seen the planet's Galilean moons look so clearly like colorful discs: like perfect little worlds, clearly distinct from stars. The planet's cloud belts and zones were phenomenally complex, with countless delicate filaments intruding from the dark belts onto the milky-white zones. The planet's southern hemisphere in particular boiled with complexity, especially in moments of seeing so good that the terrestrial atmosphere seemed simply to disappear. I observed the planet for a long time, spellbound. It was thrilling not only to feel so close to that alien world, but also to know what the Takahashi (and my entire grab-and-go kit) is really capable of. Then a sprinkler went off in the distance. It was too far to worry me - until I realized that another sprinkler could well be waiting under my feet. I quickly packed up and made my way back home. I'll come back to that field, sprinklers and all - but now other locations seem in reach, thanks to an unheralded little mount that may just be the best I've ever used. The planets are all lined up in the early morning sky, and the summer atmosphere here in DC can really settle down at night. The Sun begins to rise at around 5 AM, however, so getting up early enough to see the planets means sacrificing sleep. Still, I couldn't resist setting out twice, over the past few weeks, to catch glimpse of Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. First, on June 25th, I marched over to a nearby soccer field with my Takahashi in hand. Seeing with supposed to be better than average, while transparency was a little worse. When I set up, however, I realized that the atmosphere was actually surprisingly turbulent around the eastern horizon. That kept me from getting a good view of either Jupiter or Mars, which was quite disappointing given how tired I was. When I swung the refractor over to Saturn, however, I realized that the atmosphere was better towards the south. I had a really nice, crisp view of the planet and its rings before wisps of high-altitude cloud convinced me to pack up. A few days later, I celebrated my daughter's sixth birthday. While hauling stuff to her party, I realized that a little wagon would really help. It also dawned on me that a big enough wagon could carry my TEC 140, together with its tripod, mount, and eyepieces. I pulled the trigger and bought a UIDYGGD Folding Wagon, hoping that I could use it to haul my biggest telescope to a nearby field. In summer the leaves are just too thick, and the streetlights are just too bright, to use the TEC 140 in or near my backyard.

On the early morning of July 11th, I loaded everything into the wagon and began to wheel it towards the field. After about thirty seconds of hauling, I nearly gave up. I was dragging everything uphill, and my back was on fire. I paused, then persisted - and after fifteen minutes, reached the field. It occurred to me that there was no way I could have made it there while holding my telescope case in one hand, and pulling my rolling suitcase - which stores my tripod, mount, and eyepieces - in the other. After I set up, I turned to Mars and was rewarded with easily my best view of the planet this year. Not only was the south polar cap clearly visible, but so was a latticework of dark albedo features spidering up towards the planet's equator. Turning, to Jupiter, I was delighted to see the shadow of a Galilean moon, just beginning to emerge onto the planet's western limb. This time seeing really was better then average. It seemed there were more cloud belts than I could easily count, and there was that sensation of infinitely intricate detail that the clouds can have when Earth's atmosphere is sufficiently stable. Saturn, however, again stole the show. I've never had a view of Saturn using the TEC 140 that was quite as good as those I've enjoyed of Mars or Jupiter. But this time, with Saturn fairly high in the sky, I was treated to perhaps the sharpest view I've ever had of the planet. Not only was the Cassini Division plainly visible for the entire length of the rings, but I could make out multiple rings - which is rare for me -and the shadow of the rings on the planet was a perfect, velvet black. I also made out a whole slew of moons, and beautifully detailed, turbulent clouds on the planet's creamy yellow-white disk. It was a view that fully justified my lack of sleep - in fact, one of the best views I've ever had of a planet. I usually prefer viewing Jupiter and Mars to Saturn, because the appearance of the closer planets changes much more than that of Saturn. But when the atmosphere cooperates, the night sky offers nothing more beautiful - or more hauntingly alien - than Saturn and its rings. The planets are rising high above the early morning horizon, and for once the forecast called for good seeing. I slept fitfully until 4:15 AM, nearly convinced myself to fall back asleep, and finally slipped out the back door at 4:45. I soon found that I couldn't see a planet from my backyard, but I did find a spot nearby where a gap in the trees revealed two brilliant planets. They were remarkably close together - not much more than Jupiter and Venus were about a month ago. With the Sun beginning to brighten the morning sky, I set up my Takahashi and targeted the brightest of those planets. At first, I thought it must be Venus - that's how bright it was - and I assumed the less brilliant, yellowish planet was Jupiter. For a minute or two I thought my finderscope must be misaligned. I kept targeting the brightest planet, and time and again Jupiter showed up in the eyepiece. Finally, it dawned on me - a little later than it might have, had I had more sleep - that in fact the brilliant planet was Jupiter. I was astonished to find that the dimmer - but still very bright - planet was Mars. It's so much brighter now than it was just a month ago - and that, of course, means that it's fast approaching Earth. I was a little disappointed upon observing Jupiter. Towards the eastern horizon, the seeing was a little worse than I'd expected, and although I could make out many salmon-colored belts, shimmering in the tremulous atmosphere, the planet seemed a little washed out. It lacked the vivid reds and ochres that sometimes create such striking contrast on Jupiter. At just over 200x the Galilean moons were tiny disks, but without obvious differences in color. Mars, by contrast, was a deeper red than I've normally seen it. For the first time in two years, I made out a polar icecap - this one the southern icecap - and a dark ring around it that was, in the late nineteenth century, widely assumed to be meltwater lake draining off the cap. I could also discern dark streaks shooting up towards the Martian equator. In the nineteenth century, many astronomers - not just Percival Lowell - figured that these were canals and oases channelling polar meltwater towards cultivated fields. That was how the Martians were thought to cling to life on a drying and cooling world.

Mars is my favorite planet to observe when it nears its biannual opposition (and it's free of planet-encircling dust storms). This morning reminded me of the morning of June 9th, 2020, when I observed Mars for the first time through my FC-100DC, as it began to approach Earth that year. That morning, I was stunned to discern the southern icecap for the first time, along with dark albedo features that had never been visible to me before. It excited me to no end to realize how much more could be visible as the planet wheeled closer and closer to Earth that fall. I have much the same feeling now. I truly can't wait to see what Mars will bring this year. I wonder what I'll be able to glimpse with telescopes that are a little better than those I had in 2020. We've had plenty of clear skies lately - after a generally rainy spring - but the atmosphere has been so turbulent that I've rarely thought it worthwhile to take out a telescope. This week brought more of the same, but also something unique: a rare, close conjunction of Venus and Jupiter in the early morning sky. With the sky mostly clear, transparency quite good, and seeing a good deal worse than average, I woke up at around 5 AM last night and walked out with my Takahashi. I wasn't sure where to go. Trees blocked the view of the planets from my backyard. Before our move, I might have walked to the park I like best, but that's 20 minutes away now. By the time I got there I figured the Sun would be too high in the sky - and I'd be painfully sore from carrying everything. I wandered in that general direction all the same, and then noticed a hill I usually pass while taking my kids to the playground. I decided to walk up the hill just in case - and, sure enough, by the time I got to the top I noticed two brilliant beacons just rising into view above the eastern horizon. Jupiter and Venus! What a difference the new carbon fiber tripod makes! Walking with it is so much easier, and the FC-100DZ is much more stable now. After setting up I plugged in a 24mm Panoptic eyepiece - for a magnification of 33x - and took in the view. I'm not a big conjunction guy - I care much more about seeing details on other worlds than I do about seeing those worlds appear close together - but it was pretty impressive to see both Jupiter and Venus in the same field of view. Although seeing was very poor and it was hard to make out much detail on either world, it was easy to get a sense of just how different they are from each other, and how diverse even our little Solar System really is. It certainly helped that three of Jupiter's moons were clearly visible, and that Venus was roughly halfway illuminated. I tried to take a customary blurry cellphone picture, and just by chance at that very moment a plane zipped in front of Jupiter. As night turned to day, I packed up and walked home. When I returned to my backyard, I noticed that Jupiter and Venus were both clearly visible from a little spot near my fence. Maybe I hadn't needed to walk, after all? Still, there's always something magical about that hour before sunrise, when the city is still asleep and the loudest noises are often birdsong.

|

Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed