|

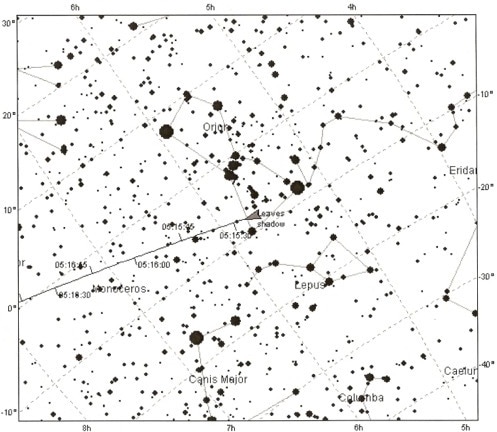

For amateur astronomers, two things happen to the atmosphere around this time of year in Washington, DC: in general, transparency improves, and seeing - meaning, of course, stability - deteriorates. Daytime brings deep blues, sunset a beautiful gradient from azure to scarlet, and nighttime brilliant winter stars in a velvet tapestry (when not facing towards the National Mall, at least). At the same time, the stars noticeably twinkle far more than they do in summer, and moments of steady seeing become ever rarer. The muggy, mosquito-plagued nights of summer, when the planets can very occasionally look like little Hubble photos viewed from afar, are now a distant memory. All the same, since keeping this blog I've found autumn to be my favorite time to observe. It's just so much more comfortable being outside, the planets are still high in the sky, and my refractors at least give me a puncher's chance of making out some detail on them, even in nights of mediocre seeing. With that in mind, I stepped out on the 14th, Takahashi in hand, and found a nook near my mostly tree-covered backyard that afforded me a good view of Mars. It was cold by DC standards - around freezing - but my telescope was well acclimated and the view was beautifully sharp. The Martian south pole in particular looked large and sort of smeared; not quite as brilliant as it can, but larger in dimensions. Later, a spectacular set of pictures posted by Peter Gorczynski over at CloudyNights.com revealed the cause: a swirl of clouds around the pole that were barely visible to me in the mediocre seeing. I didn't last long in the cold weather, and over the next week seeing here in DC grew worse - but transparency remained better than average. I decided to test out the Unistellar EVScope 2 on the comparatively few but spectacular deep space objects that are beginning to climb high above the horizon in our late autumn sky. On the 22nd, I marched about 20 minutes uphill from my house to my daughter's school. Its field is now the nearest I know that is not completely saturated with light, and I can only hope it stays that way. It's not hard to haul the EVScope that distance, thanks to the relatively ergonomic backpack it comes with, and I can only emphasize yet again how absurdly easy it is to set up the telescope once I'm in position. It takes no more than a minute to have the EVScope fully aligned and tracking my first target. It quickly and easily hooks into its tripod, immediately connects to my phone, and in just moments aligns with the night sky and slews to my first target. It takes me two or three times longer to set up my refractors on their sample manual mounts, which of course don't have any software at all. Other tracking amounts, even the simplest ones (such as the iOptron AZ Mount Pro I own), require far more steps to set up, and often don't quite align perfectly; it's why I inevitably favor manual mounts when stepping out with my refractors. I'm not sure how Unistellar leapfrogged all the established brands in amateur astronomy by offering a mount that truly is plug and play - but they have, and it's wonderful. After I let the telescope cool down, I turned to the Orion Nebula. In the past, I've tended to focus too much on my phone while the telescope slowly integrated its pictures and the view of my target gradually brightened. This time I favored the eyepiece, which as I've written elsewhere is much improved on the EvScope 2. I now noticed that the eyepiece view seemed much sharper and, to my surprise, three-dimensional than the image on my phone. The dark nebula jutting in front of the familiar crescent of the Orion Nebula, for example, truly looked as though it was in the foreground, and I followed a fascinating zigzag pattern of dark nebulosity weaving across the bright core that mostly washed out in the phone image. The EVScope permits easy if relatively low-resolution astrophotography, but the current iteration at least is really designed for observing. I've complained that using the EVScope is a very different experience from using a traditional telescope, because I've tended to wait around for the images to integrate on my phone. This time, I was glued to the eyepiece - and it really did feel like a proper observing experience. The EVScope 2 improves considerably over its predecessor, and the Unistellar software has continually added new capabilities. Just have a look at the image of the Orion Nebula that I took almost exactly two years ago, and compare it with this week's version. I suspect I could further improve the view through the EVScope 2, and I wonder what it would look like were I truly under a dark sky. Still, I find the progress to be really exciting. Just last night, I learned that Unistellar had released yet another software update: this time to enable planetary observation. I couldn't resist, and marched back to the same field. This time, however, I was a little disappointed. While the telescope for the first time automatically dimmed its images of Jupiter and Mars and showed real details on both worlds, overall the view was of course radically different from what I see through my refractors. While traditional telescopes may not as clearly reveal the cloud bands of Jupiter, for example, they show far finer and subtler detail; far more realistic and impressive coloration; and of course the moons and stars surrounding the planets.

I expected as much, but in the moment I couldn't help but be underwhelmed. Yet while walking home, I considered where the technology might be in another two years. Eventually, I suspect there will be few if any areas where traditional telescopes reign supreme. To me, their greatest value could then lie in the connection they provide to generations of observers stretching back to Galileo: to a history of often-eccentric women and men straining at odd hours to discern barely perceptible truths hidden across unimaginable distances in time and space. There are some things clever software can never replace - not many, perhaps, but some.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed