|

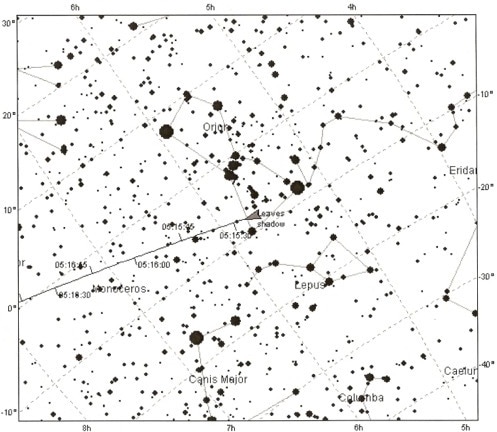

Autumn came early this year in Washington DC, yet the relative warmth of early autumn lingered well past its usual expiration date. The mosquitoes lingered with it, even if their population fell with the leaves, but overall it's been a gorgeous month in the city. Over the past week, we had three crisp, clear nights with tolerably good seeing and transparency. With the canopies above my yard increasingly bare, I was able to peak through and branches and observe without hauling heavy gear for twenty exhausting minutes. A few nights ago, I rolled out my TEC 140 to observe the Moon and Jupiter. Night comes early at this time of the year, of course, so I made it outside before my six-year-old daughter's bedtime. I asked her to join me, and when she did she was thrilled to make out craters on the Moon and, with some difficulty, cloud bands on Jupiter. To my surprise, those were unusually difficult to make out. The sky had a milky quality around bright objects, a kind of watercolor softness, that seemed to obscure detail on the likes of Jupiter. Still, a memorable experience for daughter and daddy alike. On November 8th, conditions promised to be marginally better, and temperatures were just about ideal. This time, I stepped out with a much lighter setup: my Takahashi FC-100DZ, clamped to the CT-20 mount that I'd screwed into my Berlebach Uni tripod. It's a more robust outfit than I take to the local park, but it's still easy to move all in one go. A quick aside: the exceptional weight of the DM-6 mount can make it really sturdy and capable of handling surprisingly hefty telescopes. Yet it also ruins the portability of my TEC 140. The mount feels at least as heavy as the telescope, and when yoked to a tripod it's a chore to move even without the telescope attached. Another problem is that attaching the telescope to the DM-6 mount is a heart-stopping experience in the dark. It's hard to be sure that the dovetail is actually in the clamp, and I've now been unpleasantly surprised several times when the telescope suddenly lurched down after I thought I'd got it in. I live in fear that on some sad night I'll misjudge it, step away, and watch in horror as the telescope crashes to the ground. I have no such problem with the Takahashi. Yet the lightness of the CT-20 mount does mean that the telescope tends to tilt - even when perfectly balanced - if objects are too close to zenith. The CT-20 has an answer, however: it's easy to adjust the tension in the altitude and azimuth axes. This can mean that there's too much tension to easily nudge the telescope along when observing objects that are high up in the sky, but I'll take the tradeoff: less weight and less hassle is worth some compromise. In any case, the Takahashi gave me some very satisfactory views of the waning but still nearly full Moon. The view along the emerging terminator in particular was quite striking, while the Moon's fully illuminated surface showed a mesmerizing swirl of subtle grey shadings. The rays streaking from Tycho, one of the youngest big craters on the lunar surface, are always impressive when the Moon is this close to full. Yet Mars is now wheeling towards its biannual opposition, so of course it stole the show. The planet is quite high in the sky by around 10 PM EST, and it's already brighter than any celestial body visible at that time save Jupiter and the Moon. I feel that its color even by naked eye is not quite as blood-red as it was two years ago; it's paler and a little closer to orange. The Takahashi revealed its waxing globe, but showed considerably less contrast than I could make out a couple years back. In moments of good seeing I could make out the south polar icecap, and then a dark albedo swirl around the ice, interrupted by lighter land before continuing towards the north. Yet the view was anything but sharp, and the planet seemed unsteady somehow in the mediocre seeing. Part of the problem is that much of Mars is currently obscured by bright dust storm: a common if frustrating occurrence when Mars makes a close approach to the Sun. It was to gain a clearer view of the Moon and Mars that I stepped out last night with the TEC 140. Conditions seemed about the same, except it was colder and the reappearance of a halo around the Moon suggested that transparency would be lower. The TEC takes meaningly longer to cool down than the Takahashi, although in both cases the Delos eyepieces take longer to acclimate than the telescopes. I'm not sure it's widely understood that compound eyepieces take longer to cool down than, say, Plossl eyepieces - but that's certainly been my experience, and it does stand to reason. There's just a lot of glass in those things.

In any case, both refractors and their eyepieces need only a few minutes to give acceptable views, even if they do take longer to fully acclimate. When everything was ready I was surprised to find that the TEC 140 actually provided slightly softer views than the Takahashi did the other night, even if contrast on Mars in particular seemed just a bit higher, and the Moon's terminator at times snapped into exquisite if fleeting focus. I was once again impressed by the Takahashi; despite its compact size, I rarely feel I'm missing out when I use that telescope, the way I did with many other small telescopes I've owned. It punches far above it weight. Yet to me the bigger takeaway was that the difference between telescopes is often completely swamped by atmospheric conditions. In mediocre seeing and transparency, there really isn't much of a divide between the $8000 (!) TEC 140 and the $3000 Takahashi (of course both telescopes have world-class optics; even in bad seeing, I would suspect a meaningful difference between them and a run-of-the-mill refractor). In my years of observing here in DC, I can probably count on one hand the nights on which the atmosphere was so stable and clear that I could use magnifications of 200x or more. The pricey difference between optics is often less apparent here than it would be elsewhere, and I think that's something observers should acknowledge more often. Where you live will dictate the gains you get by spending more on bigger and fancier telescopes. William Sheehan - who publishes some of the most engaging books on the history and practice of planetary and lunar observing - writes that as an observer views Mars near opposition, "over it, intermittently, uncertain details dart and then are gone like doubtful visions." None other than Percival Lowell - a key popularizer of the Mars canal theory, among other things - coined the term "revelation peeps" to describe these sudden glimpses of intricate detail. That is precisely what Mars had on offer tonight. It wobbled and wavered, like a coin seen through the burbling water of a fountain. Then, for fractions of a second, it snapped into sharp relief, looking really and truly like a planet seen from an approaching spaceship. Just before my brain could grapple with that new reality, the planet reverted so quickly to an indistinct blob that I could scarcely believe it had ever been otherwise. Mars! Always so difficult, but oh so compelling.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed