|

Tonight was one of those relatively rare wintry nights in Washington, DC, where atmospheric transparency is high while seeing is better than average. With Mars just four days away from opposition - its biannual closest approach to Earth - I couldn't let the opportunity slip. The canopies above my backyard are now sufficiently denuded for me to use a telescope just a few steps from my door, so out I stepped with my TEC 140. The Moon was just about to slip behind my building, and I was hard pressed to get a quick picture. The view was in fact beautifully sharp, what you see above is the only shot I could get. I also managed to get a quick look at Jupiter, where to my surprise it seemed that one moon - near the limb of Jupiter - was far below the orbital plane set by the other moons. I don't think I've seen that before. Eventually, I found a comfortable nook from which to observe Mars. Seeing seemed a good deal better than average tonight, and the outline of the planet was about as sharp and steady as I've ever seen it. I was struck by how much smaller it seemed than it did during its last opposition, two years ago, when it looked only marginally smaller than it did during its perihelic opposition of 2018. Of course, my gear has improved since then, so the views of Mars I've had this year haven't been much worse than those I had in 2020. Still, the planet's apparent diameter is only about 17 arcseconds this year - down from 22.4 in 2020, and a whopping 24.2 in 2018. In fact, not since 2014 has Mars looked so unimposing at opposition.

More important for viewing Mars than the apparent size of the planet or my equipment, however, has been dust. In 2018, I couldn't make out any details on Mars while using my Skywatcher 100ED, and that owed more to a yellow, planet-wide dust storm than the lack of perfect color correction on the refractor. In 2020, Mars was relatively dust-free, and so a deeper shade of red. I was ready then with a pair of telescopes (my dearly departed APM 140 and Takahashi FC-100DC) that were only slightly less capable than those I own today. Now Mars seems dusty and a bit yellowish again, but not as much as it was in 2018. Surface detail has obvious through my TEC 140 and Takahashi FC-100DZ, though not as much as it was in 2020, and the planet's disk is comparatively small. I replaced my APM 140 with the TEC 140ED, and my FC-100DC with the FC100DZ, in large part to prepare for this year's opposition. I'm glad I did, but in making those replacements I've also come to realize that there really are rapidly diminishing returns for costly upgrades in this hobby. Yes, views through the DZ seem marginally better than the ones I enjoyed with my wonderful DC, but from night to night conditions in our atmosphere - and that of Mars - are much more important. Tonight I was again reminded of how trifling differences in performance between optics can be enormously exaggerated in online discussions. It's widely held that high-contrast eyepieces such as the TeleVue Delos will easily outperform zoom eyepieces, including the latest iteration of the Baader Hyperion Zoom. While switching between the zoom eyepiece and the Delos 4.5mm and 6mm eyepieces, however, I found that magnification affected the view far more than the eyepiece I was using. The view seemed just right at around 160x; any more than that, and it got a little blurry. Both the Baader and TeleVue eyepieces provided striking and at times rather complex views of Mare Cimmerium at that magnification, along with flashes of Trivium Charontis and perhaps some other dark regions in the northern hemisphere of Mars. I thought I might have caught some hints of white swaths far to the south, but they were hard to pin down; I fancied they might be clouds. I saw very little to separate the eyepieces, but I eventually found myself settling with the 6mm Delos because of its larger field of view. If pressed I might confess that dark albedo regions were more consistently obvious in the Delos than the Baader Zoom - but that may be only because I expected to see them more clearly in the Delos. One thing's for sure: I'll never again assume that I'm missing out by using the zoom eyepiece as opposed to a Delos, and I'll be a little more careful when reading claims that one premium eyepiece or telescope is clearly superior to another. I hope to have another chance to observe Mars this week, and certainly this month, but if not tonight was a wonderful way to mark the planet's opposition.

0 Comments

For amateur astronomers, two things happen to the atmosphere around this time of year in Washington, DC: in general, transparency improves, and seeing - meaning, of course, stability - deteriorates. Daytime brings deep blues, sunset a beautiful gradient from azure to scarlet, and nighttime brilliant winter stars in a velvet tapestry (when not facing towards the National Mall, at least). At the same time, the stars noticeably twinkle far more than they do in summer, and moments of steady seeing become ever rarer. The muggy, mosquito-plagued nights of summer, when the planets can very occasionally look like little Hubble photos viewed from afar, are now a distant memory. All the same, since keeping this blog I've found autumn to be my favorite time to observe. It's just so much more comfortable being outside, the planets are still high in the sky, and my refractors at least give me a puncher's chance of making out some detail on them, even in nights of mediocre seeing. With that in mind, I stepped out on the 14th, Takahashi in hand, and found a nook near my mostly tree-covered backyard that afforded me a good view of Mars. It was cold by DC standards - around freezing - but my telescope was well acclimated and the view was beautifully sharp. The Martian south pole in particular looked large and sort of smeared; not quite as brilliant as it can, but larger in dimensions. Later, a spectacular set of pictures posted by Peter Gorczynski over at CloudyNights.com revealed the cause: a swirl of clouds around the pole that were barely visible to me in the mediocre seeing. I didn't last long in the cold weather, and over the next week seeing here in DC grew worse - but transparency remained better than average. I decided to test out the Unistellar EVScope 2 on the comparatively few but spectacular deep space objects that are beginning to climb high above the horizon in our late autumn sky. On the 22nd, I marched about 20 minutes uphill from my house to my daughter's school. Its field is now the nearest I know that is not completely saturated with light, and I can only hope it stays that way. It's not hard to haul the EVScope that distance, thanks to the relatively ergonomic backpack it comes with, and I can only emphasize yet again how absurdly easy it is to set up the telescope once I'm in position. It takes no more than a minute to have the EVScope fully aligned and tracking my first target. It quickly and easily hooks into its tripod, immediately connects to my phone, and in just moments aligns with the night sky and slews to my first target. It takes me two or three times longer to set up my refractors on their sample manual mounts, which of course don't have any software at all. Other tracking amounts, even the simplest ones (such as the iOptron AZ Mount Pro I own), require far more steps to set up, and often don't quite align perfectly; it's why I inevitably favor manual mounts when stepping out with my refractors. I'm not sure how Unistellar leapfrogged all the established brands in amateur astronomy by offering a mount that truly is plug and play - but they have, and it's wonderful. After I let the telescope cool down, I turned to the Orion Nebula. In the past, I've tended to focus too much on my phone while the telescope slowly integrated its pictures and the view of my target gradually brightened. This time I favored the eyepiece, which as I've written elsewhere is much improved on the EvScope 2. I now noticed that the eyepiece view seemed much sharper and, to my surprise, three-dimensional than the image on my phone. The dark nebula jutting in front of the familiar crescent of the Orion Nebula, for example, truly looked as though it was in the foreground, and I followed a fascinating zigzag pattern of dark nebulosity weaving across the bright core that mostly washed out in the phone image. The EVScope permits easy if relatively low-resolution astrophotography, but the current iteration at least is really designed for observing. I've complained that using the EVScope is a very different experience from using a traditional telescope, because I've tended to wait around for the images to integrate on my phone. This time, I was glued to the eyepiece - and it really did feel like a proper observing experience. The EVScope 2 improves considerably over its predecessor, and the Unistellar software has continually added new capabilities. Just have a look at the image of the Orion Nebula that I took almost exactly two years ago, and compare it with this week's version. I suspect I could further improve the view through the EVScope 2, and I wonder what it would look like were I truly under a dark sky. Still, I find the progress to be really exciting. Just last night, I learned that Unistellar had released yet another software update: this time to enable planetary observation. I couldn't resist, and marched back to the same field. This time, however, I was a little disappointed. While the telescope for the first time automatically dimmed its images of Jupiter and Mars and showed real details on both worlds, overall the view was of course radically different from what I see through my refractors. While traditional telescopes may not as clearly reveal the cloud bands of Jupiter, for example, they show far finer and subtler detail; far more realistic and impressive coloration; and of course the moons and stars surrounding the planets.

I expected as much, but in the moment I couldn't help but be underwhelmed. Yet while walking home, I considered where the technology might be in another two years. Eventually, I suspect there will be few if any areas where traditional telescopes reign supreme. To me, their greatest value could then lie in the connection they provide to generations of observers stretching back to Galileo: to a history of often-eccentric women and men straining at odd hours to discern barely perceptible truths hidden across unimaginable distances in time and space. There are some things clever software can never replace - not many, perhaps, but some. Autumn came early this year in Washington DC, yet the relative warmth of early autumn lingered well past its usual expiration date. The mosquitoes lingered with it, even if their population fell with the leaves, but overall it's been a gorgeous month in the city. Over the past week, we had three crisp, clear nights with tolerably good seeing and transparency. With the canopies above my yard increasingly bare, I was able to peak through and branches and observe without hauling heavy gear for twenty exhausting minutes. A few nights ago, I rolled out my TEC 140 to observe the Moon and Jupiter. Night comes early at this time of the year, of course, so I made it outside before my six-year-old daughter's bedtime. I asked her to join me, and when she did she was thrilled to make out craters on the Moon and, with some difficulty, cloud bands on Jupiter. To my surprise, those were unusually difficult to make out. The sky had a milky quality around bright objects, a kind of watercolor softness, that seemed to obscure detail on the likes of Jupiter. Still, a memorable experience for daughter and daddy alike. On November 8th, conditions promised to be marginally better, and temperatures were just about ideal. This time, I stepped out with a much lighter setup: my Takahashi FC-100DZ, clamped to the CT-20 mount that I'd screwed into my Berlebach Uni tripod. It's a more robust outfit than I take to the local park, but it's still easy to move all in one go. A quick aside: the exceptional weight of the DM-6 mount can make it really sturdy and capable of handling surprisingly hefty telescopes. Yet it also ruins the portability of my TEC 140. The mount feels at least as heavy as the telescope, and when yoked to a tripod it's a chore to move even without the telescope attached. Another problem is that attaching the telescope to the DM-6 mount is a heart-stopping experience in the dark. It's hard to be sure that the dovetail is actually in the clamp, and I've now been unpleasantly surprised several times when the telescope suddenly lurched down after I thought I'd got it in. I live in fear that on some sad night I'll misjudge it, step away, and watch in horror as the telescope crashes to the ground. I have no such problem with the Takahashi. Yet the lightness of the CT-20 mount does mean that the telescope tends to tilt - even when perfectly balanced - if objects are too close to zenith. The CT-20 has an answer, however: it's easy to adjust the tension in the altitude and azimuth axes. This can mean that there's too much tension to easily nudge the telescope along when observing objects that are high up in the sky, but I'll take the tradeoff: less weight and less hassle is worth some compromise. In any case, the Takahashi gave me some very satisfactory views of the waning but still nearly full Moon. The view along the emerging terminator in particular was quite striking, while the Moon's fully illuminated surface showed a mesmerizing swirl of subtle grey shadings. The rays streaking from Tycho, one of the youngest big craters on the lunar surface, are always impressive when the Moon is this close to full. Yet Mars is now wheeling towards its biannual opposition, so of course it stole the show. The planet is quite high in the sky by around 10 PM EST, and it's already brighter than any celestial body visible at that time save Jupiter and the Moon. I feel that its color even by naked eye is not quite as blood-red as it was two years ago; it's paler and a little closer to orange. The Takahashi revealed its waxing globe, but showed considerably less contrast than I could make out a couple years back. In moments of good seeing I could make out the south polar icecap, and then a dark albedo swirl around the ice, interrupted by lighter land before continuing towards the north. Yet the view was anything but sharp, and the planet seemed unsteady somehow in the mediocre seeing. Part of the problem is that much of Mars is currently obscured by bright dust storm: a common if frustrating occurrence when Mars makes a close approach to the Sun. It was to gain a clearer view of the Moon and Mars that I stepped out last night with the TEC 140. Conditions seemed about the same, except it was colder and the reappearance of a halo around the Moon suggested that transparency would be lower. The TEC takes meaningly longer to cool down than the Takahashi, although in both cases the Delos eyepieces take longer to acclimate than the telescopes. I'm not sure it's widely understood that compound eyepieces take longer to cool down than, say, Plossl eyepieces - but that's certainly been my experience, and it does stand to reason. There's just a lot of glass in those things.

In any case, both refractors and their eyepieces need only a few minutes to give acceptable views, even if they do take longer to fully acclimate. When everything was ready I was surprised to find that the TEC 140 actually provided slightly softer views than the Takahashi did the other night, even if contrast on Mars in particular seemed just a bit higher, and the Moon's terminator at times snapped into exquisite if fleeting focus. I was once again impressed by the Takahashi; despite its compact size, I rarely feel I'm missing out when I use that telescope, the way I did with many other small telescopes I've owned. It punches far above it weight. Yet to me the bigger takeaway was that the difference between telescopes is often completely swamped by atmospheric conditions. In mediocre seeing and transparency, there really isn't much of a divide between the $8000 (!) TEC 140 and the $3000 Takahashi (of course both telescopes have world-class optics; even in bad seeing, I would suspect a meaningful difference between them and a run-of-the-mill refractor). In my years of observing here in DC, I can probably count on one hand the nights on which the atmosphere was so stable and clear that I could use magnifications of 200x or more. The pricey difference between optics is often less apparent here than it would be elsewhere, and I think that's something observers should acknowledge more often. Where you live will dictate the gains you get by spending more on bigger and fancier telescopes. William Sheehan - who publishes some of the most engaging books on the history and practice of planetary and lunar observing - writes that as an observer views Mars near opposition, "over it, intermittently, uncertain details dart and then are gone like doubtful visions." None other than Percival Lowell - a key popularizer of the Mars canal theory, among other things - coined the term "revelation peeps" to describe these sudden glimpses of intricate detail. That is precisely what Mars had on offer tonight. It wobbled and wavered, like a coin seen through the burbling water of a fountain. Then, for fractions of a second, it snapped into sharp relief, looking really and truly like a planet seen from an approaching spaceship. Just before my brain could grapple with that new reality, the planet reverted so quickly to an indistinct blob that I could scarcely believe it had ever been otherwise. Mars! Always so difficult, but oh so compelling. Earlier this month, I set forth on a night of above-average seeing to the field that has become my favorite observing spot, just an eight minutes' walk from our new home. I heaved up the hill bordering the field, hauling my Takahashi and an uncomfortably heavy backpack, full of expectations. As I rounded the top of the hill, I saw . . . this. It's one thing to install new lights, but these were about the brightest I've seen in Washington, DC. I could scarcely believe my now not-at-all dark adapted eyes. Another observing spot - my third, since this blog began - ruined by newly installed, fluorescent lighting. It's demoralizing to experience firsthand how every patch of dark sky in the city is steadily being surrounded and at last consumed by unnecessary light. I wandered home, too stunned, too sore, and too tired to find another location to set up. In the days that followed, I reviewed my options. I wandered around my home, and found another location, in a neighborhood garden, just a bit farther than the field - but a lot more overgrown with bushes and trees, and no doubt overrun by summer bugs. Then there was another field, perhaps a 20-minute walk away, and (for now) dark at night. Wherever I went, it would be farther: and I had trouble enough walking the eight minutes to the now unusable field. I decided I had to reduce the weight of my grab-and-go setup, and in particular ease the strain on my shoulders. But how? MY DM-4, I thought, was about the lightest mount I could use with my Takahashi FC-100DZ. I agonized over whether to exchange the telescope for something smaller and less capable. I bought it in the first place because it was the biggest and best telescope - that cooled down quickly and provided spectacular lunar and planetary views - I could easily walk with for 10 or 15 minutes. But 20 minutes? And with the mount I needed, and my eyepieces? Eventually I figured that the step down to something smaller - a Takahashi FC-76 DCU, for example - was just too big a fall to be worthwhile. Since my tripod is already wonderfully light, I was left with my eyepieces and mount. The eyepiece problem was easy to solve. Rather than carry four Delos eyepieces, I decided to take just one eyepiece with me: a Baader Mark IV Variable Zoo. When equipped with its barlow lens, it would give me all the magnification I could want. There was a cost: a marginal loss in sharpness, perhaps, and a meaningful loss in field of view (which means something with a manual mount). Still, I found it a small price to pay compared to the alternative (swapping telescopes). I also started researching mounts. Readers will know I settled on the DM-4 after using an AYO II mount. Both mounts are impressive. The AYO II is lighter than the DM-4 and more compact, even as it seemed less durable. Now I wondered whether to exchange the DM-4 for another AYO II; weight, it seemed to me, had to come first. However, I soon found some intriguing newcomers in the quality manual mount market. One in particular stood out: the CT-20 by NoH's Mount, a little company owned by an independent craftsman in South Korea. On paper, the CT-20 weighed less than half as much as the DM-4 (and a third less than the AYO II), while being more compact than both. It cost less and handled more weight. It seemed almost too good to be true - but I bought it, and sold the DM-4. To my surprise, on the night the CT-20 arrived from South Korea, the sky was clear and both seeing and transparency were well above average. I greedily unpacked the little mount, hoping I'd be able to use it immediately. I was immediately impressed - and, to be honest, a little surprised - to find that its build quality seemed exceptionally high, on par certainly with the AYO II and DM-4. I was also delighted to find that the mount is even more compact than I'd expected (this is a rarity in amateur astronomy, where things tend to be much bigger than you thought they'd be).

This time I packed my mount and eyepiece into a much smaller, more comfortable backpack; all in all, I think I shaved about ten pounds from the load I had to carry. I walked the 20 minutes to the more distant field, and was delighted to find that I still had some energy left - and that the field was mercifully dark. I unpacked, set up, and to my astonishment soon found the mount at least as stable with the Takahashi as the DM-4 - and that without the vibration suppression pads that I used with the bigger mount! It also allowed my telescope to easily clear my tripod; with the DM-4, I'd needed a ($250!) tripod extender for that. I quickly slewed to the Moon, and there encountered another surprise: a stunningly sharp view of the lunar terminator in the best seeing I've experienced all year. The mountains on the lunar terminator in particular took on a gloriously three-dimensional character, and I easily made out countless subtle rilles and scarps. Rupes Recta, the so-called "Straight Wall" of the Moon, was perfectly illuminated and a particularly striking sight. I got a genuine sense - maybe for the first time - of how eighteenth- and nineteenth-century astronomers could have mistaken rectilinear features on the Moon for signs of intelligent life. I'm not sure a Delos eyepiece would have afforded a better view; in fact, I couldn't imagine a better view. Next up was Jupiter, and wow: what a sight. I have never - not even with my TEC 140 - seen the planet's Galilean moons look so clearly like colorful discs: like perfect little worlds, clearly distinct from stars. The planet's cloud belts and zones were phenomenally complex, with countless delicate filaments intruding from the dark belts onto the milky-white zones. The planet's southern hemisphere in particular boiled with complexity, especially in moments of seeing so good that the terrestrial atmosphere seemed simply to disappear. I observed the planet for a long time, spellbound. It was thrilling not only to feel so close to that alien world, but also to know what the Takahashi (and my entire grab-and-go kit) is really capable of. Then a sprinkler went off in the distance. It was too far to worry me - until I realized that another sprinkler could well be waiting under my feet. I quickly packed up and made my way back home. I'll come back to that field, sprinklers and all - but now other locations seem in reach, thanks to an unheralded little mount that may just be the best I've ever used. Binoculars have long frustrated me. While I've thrilled at catching glimpses of rocket launches or lunar craters with big Celestron binoculars here in Washington, DC, I could never hold them steady enough to make out more than blurry glimpses. I opted for more manageable binoculars, but still: no matter what I did, the view was always disappointing. Eventually I gave up and decided that binoculars were just not for me. Then I learned about image stabilized binoculars: remarkable little devices that use gyroscopes and moveable lenses to cancel the inevitable vibrations caused by human hands. The high cost and relatively small size of these binoculars at first convinced me that it just wouldn't be worth it to buy one. Eventually, however, I found that I'd accumulated a heap of eyepieces I no longer used, and after selling them I took the plunge. I bought a pair of Canon 12x36 Image Stabilization III binoculars. When they arrived, I decided to try them out on the abundant birds in my backyard. I'm not a bird watcher - the one time I went on a bird watching tour at a conference, I was nearly abandoned in the middle of a desert - but I have to say, I was absolutely floored by the view. It really felt like the bird I was looking at - a female cardinal high up in the canopy - was right there in front of me on the table. The view was absolutely crisp, razor-sharp with no false color, and better yet: it was stable. It's hard to emphasize enough what a difference that makes. I was eager to see what I could make out on the planets, which had become very prominent in the mornings. When I tried, however, I was disappointed. This time I noticed some false color, and the image wasn't quite sharp enough for me. I figured, sadly, that even the best binoculars might not have much value for me in astronomy. Yet last night I couldn't resist the temptation to try out the binoculars one more time. The last "supermoon" of the year was rising, the Perseid meteor shower was peaking, and I really wanted to go to my favorite park. It's a long and painful hike with a telescope, but easy and fun while riding a scooter with one-pound binoculars in a backpack. I zipped out at around 11 PM, and made it to the park in no time.

The very first thing I saw as I reached my preferred observing spot was a bright meteor: an auspicious start if ever there was one. When I looked at the huge, golden Moon, however, I was again disappointed: it was just a bit blurry, with too much false color. This time I carefully adjusted the binocular's collimation and focus, waited a few minutes for it to acclimate, and tried again. What a difference! Now the Moon was wonderfully sharp - like those birds in my backyard - and to my astonishment the view really wasn't much less impressive than it is with my Takahashi refractor at low magnifications. The amount of detail I could make out was nothing short of miraculous. Then I turned to Saturn, and could hardly believe it when I easily made out its rings. Jupiter was rising above the horizon, and sure enough: there were its moons, perfectly clear in binoculars with an aperture of just 36mm. There was something exhilarating about how easy it all was. The binoculars are little bigger than my hand, and of course they required essentially no setup. But there I was, with bats fluttering overhead (I saw one through the binoculars), admiring the heavens. After about 15 minutes, I had that giddy feeling I sometimes get during my best nights under the stars - and since I wanted to leave on a high note, I hopped back on my scooter and sped home. Image-stabilized binoculars cost a lot more than a decent pair of regular binoculars (but a lot less than premium binoculars with high-quality optics). However, I'm now convinced that it's difficult to compare them to their lower-tech cousins. It's a completely different experience to use them. Because their views are stable, looking through them is more like using a telescope than regular binoculars - with the added benefit of the three-dimensional experience that binoculars (or binoviewers) uniquely provide. I have a real weakness for little instruments that provide outsized views (it's why I loved my TV 85 as much as I did). After last night, I have to conclude that the diminutive Canon 12x36 is, quite possibly, the most impressive optical instrument I've ever tried out. It doesn't often work out this way in amateur astronomy, but sometimes big things really do come in little packages. The planets are all lined up in the early morning sky, and the summer atmosphere here in DC can really settle down at night. The Sun begins to rise at around 5 AM, however, so getting up early enough to see the planets means sacrificing sleep. Still, I couldn't resist setting out twice, over the past few weeks, to catch glimpse of Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. First, on June 25th, I marched over to a nearby soccer field with my Takahashi in hand. Seeing with supposed to be better than average, while transparency was a little worse. When I set up, however, I realized that the atmosphere was actually surprisingly turbulent around the eastern horizon. That kept me from getting a good view of either Jupiter or Mars, which was quite disappointing given how tired I was. When I swung the refractor over to Saturn, however, I realized that the atmosphere was better towards the south. I had a really nice, crisp view of the planet and its rings before wisps of high-altitude cloud convinced me to pack up. A few days later, I celebrated my daughter's sixth birthday. While hauling stuff to her party, I realized that a little wagon would really help. It also dawned on me that a big enough wagon could carry my TEC 140, together with its tripod, mount, and eyepieces. I pulled the trigger and bought a UIDYGGD Folding Wagon, hoping that I could use it to haul my biggest telescope to a nearby field. In summer the leaves are just too thick, and the streetlights are just too bright, to use the TEC 140 in or near my backyard.

On the early morning of July 11th, I loaded everything into the wagon and began to wheel it towards the field. After about thirty seconds of hauling, I nearly gave up. I was dragging everything uphill, and my back was on fire. I paused, then persisted - and after fifteen minutes, reached the field. It occurred to me that there was no way I could have made it there while holding my telescope case in one hand, and pulling my rolling suitcase - which stores my tripod, mount, and eyepieces - in the other. After I set up, I turned to Mars and was rewarded with easily my best view of the planet this year. Not only was the south polar cap clearly visible, but so was a latticework of dark albedo features spidering up towards the planet's equator. Turning, to Jupiter, I was delighted to see the shadow of a Galilean moon, just beginning to emerge onto the planet's western limb. This time seeing really was better then average. It seemed there were more cloud belts than I could easily count, and there was that sensation of infinitely intricate detail that the clouds can have when Earth's atmosphere is sufficiently stable. Saturn, however, again stole the show. I've never had a view of Saturn using the TEC 140 that was quite as good as those I've enjoyed of Mars or Jupiter. But this time, with Saturn fairly high in the sky, I was treated to perhaps the sharpest view I've ever had of the planet. Not only was the Cassini Division plainly visible for the entire length of the rings, but I could make out multiple rings - which is rare for me -and the shadow of the rings on the planet was a perfect, velvet black. I also made out a whole slew of moons, and beautifully detailed, turbulent clouds on the planet's creamy yellow-white disk. It was a view that fully justified my lack of sleep - in fact, one of the best views I've ever had of a planet. I usually prefer viewing Jupiter and Mars to Saturn, because the appearance of the closer planets changes much more than that of Saturn. But when the atmosphere cooperates, the night sky offers nothing more beautiful - or more hauntingly alien - than Saturn and its rings. It was Father's Day yesterday, and I had sanction to wake up late. When I found out the night would be clear, I was full of anticipation - until I realized that seeing was forecast to be about as bad as I can remember. I stepped out after sundown, however, and found the stars unusually visible in the night sky. Sure enough, transparency was high above average - which made sense, as the night as unusually crisp for a DC summer. Out I stepped at around 1:30 AM, burdened like a Tolkien dwarf with the EVScope II on my back, and a tripod in hand. This time I walked to a nearby school's soccer pitch, which not only affords an impressive view of the whole sky but is also (strangely) bereft of street lights. I set up in a few seconds, then targeted the heart of the Milky Way as it rose well above the southeastern horizon. The light pollution is very bad in that direction - it's right above the National Mall - but still, I had high hopes. I've largely praised the EVScope in these pages, and rightfully so. In a matter of moments the Omega Nebula emerged from the background light pollution, and wow that is an impressive effect. After a five-minute exposure, I moved on to the Lagoon Nebula, with much the same results. I now slewed to the Owl Nebula, but this time the view underwhelmed - even after five minutes - and it's not surprising: at around tenth magnitude, it's a challenge for the EVScope in light-polluted skies. As the chill began to set in, I finished up with the Sunflower Galaxy: a faint spiral roughly the size of the Milky Way, 27 million light years distant. It was a subtle view after six minutes or so, but still recognizable. I had profoundly mixed feelings as I walked home. On the one hand, it continues to amaze me that the EVScope brings nebulae and galaxies within my reach, from downtown DC. On the other - and this can't be stressed enough - using the telescope is not comparable to traditional observing. With a regular telescope, the bulk of your time is spent straining at the eyepiece. You train yourself to see like observers have for centuries - using averted vision, for example - and there's an art to it that you can improve over time. When you're not observing the obviously spectacular - Saturn or the Moon, for example - then what's visible through the eyepiece can be absurdly subtle. The average person would never recognize, let alone appreciate, what you can just barely glimpse. What makes it special is the sensation of seeing with your own eyes what can otherwise be admired only in enhanced pictures. You are truly experiencing the universe, albeit only as well as imperfect optics and a turbulent atmosphere will permit on any given night. With the EVScope, by contrast, you navigate an app on your phone. You stare at a screen as the telescope effortlessly targets and then observes your chosen object for you. Slowly, a picture emerges of the object you've selected. It's a little like a picture you can Google - something taken by Hubble, for example - except way worse. As the picture slowly brightens, you wait. You scroll through other stuff on your phone, perhaps, or you sit there thinking. One thing is for sure: most of the time, you aren't actually looking at space at all. Eventually, you turn your attention back to the app and if you're satisfied enough with the picture, you target something else. You end up with pictures that look impressive when they're small, on your phone, but - owing to their resolution or the unavoidable influence of light pollution - underwhelm when you blow them up on your laptop.

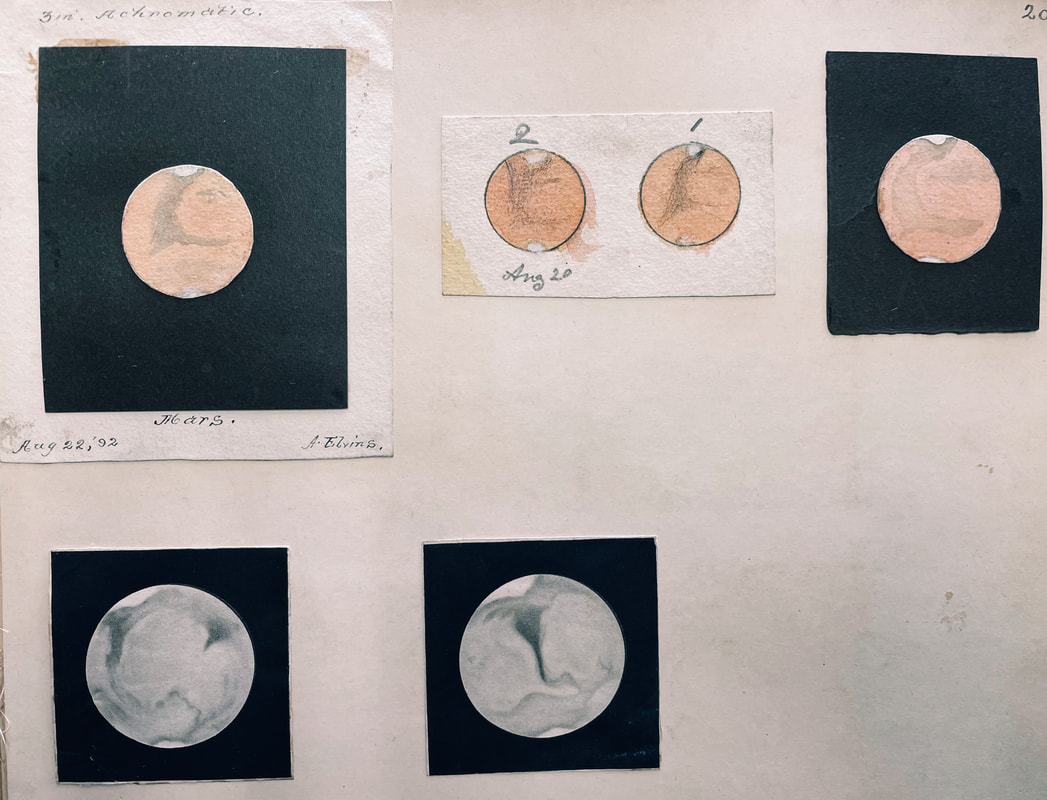

It's exciting to find what's out there, in the sky, that you could never see with traditional optics (barring a difficult-to-use astrophotography setup, of course). But sometimes, walking home, the experience leaves you cold. Sometimes, you feel like all you've done is played with screens. You haven't really experienced nature, and you certainly haven't learned an art. Everything was easy, so occasionally it feels like little was gained. You might as well played with a screen at home. On some nights, the EVScope can feel like a toy - whereas a more traditional telescope always feels like a tool. Maybe that's because of how and where I'm using the EVScope. Maybe the telescope could do more under a darker sky, and certainly the EVScope comes with citizen science features that I haven't begun to access yet. But with the similarly-priced FC 100DZ, for example, I feel like I'm engaging in an old art with a rich history. With the EVScope, I often feel more like I'm playing a game on my phone. Both have their virtues, but if I had to choose one telescope - it would be the refractor. Summer has truly begun in DC when the forecast calls for back-to-back nights with good seeing, and the planets begin to rise high above the horizon. After a very satisfying morning with my Takahashi FC-100DZ, gazing at the southern icecap of Mars, I hauled out my TEC 140 last night and found the same gap in the trees. Once again, there were Mars and Jupiter in the pellucid morning sky, in good (if not exactly great) seeing. I'd swapped my DM-4 mount for a DM-6, and my carbon fiber tripod for a Berlebach Uni. The heavier ensemble is much more pleasant to use. As I've written in these pages, there's just not beating the mechanical quality of TEC. Every aspect of the 140 is a joy to see and a pleasure to manipulate. The DM-6 and Uni hold the telescope exceptionally well, with virtually no vibrations even when I adjust the buttery-smooth Feathertouch focuser. If I could have just one setup: yes, it would be this. I've often found an easily noticeable difference at the eyepiece between quality 4- and 5.5-inch refractors. The TEC in particular has given me my finest-ever views of Jupiter and the Moon, with an ethereal, three-dimensional quality and the sensation of texture that I've never had with another telescope. This morning, however, I was mildly surprised to find that the view resembled what I'd seen the previous morning, using the FC-100DZ. Granted, I could see a star near Mars that I hadn't sighted with the smaller refractor, and the cloud belts of Jupiter definitely showed more detail in moments of steady seeing. At well over 200x, a dark albedo feature on Mars seemed to more clearly extend north from the southern icecap, which of course I could make out clearly. Yet the difference was, overall, insubstantial. I think amateur astronomers too often exaggerate the importance of equipment in what they can discern at the eyepiece, and too often understate the influence of the atmosphere. In my experience, even subtle atmospheric differences from night to night - and from one part of the sky to the other - can matter more than very substantial differences in equipment (that might make one setup cost many thousands of dollars more than another). It's humbling to know that a $150 telescope - such as the C90 - could outperform an $8000 refractor (such as the TEC 140) on any given night. I also wonder to what extent nearby streetlights were running interference, softening the view at the eyepiece. Something like that seems to have happened to me before, when my FC-100DC suddenly showed garish chromatic aberration as I observed the Moon under some bright lights. In any case, several dark markings - barges? - were fleetingly visible in what I took to be the north equatorial and north temperate cloud belts of Jupiter. I was again struck by the pale and almost washed-out view of the planet, where contrast has often seemed so stark with a 5.5-inch refractor. I thought I could make out a very faded Great Red Spot: not much more than a subtle blotch in the planet's southern hemisphere. After I packed up, I reflected on a recent trip to some astronomical archives, which I consulted to complete my next book, Ripples in the Cosmic Ocean. Among other stops, my travels took me to the archive of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, which is tucked away in a little office on the second-story of a nondescript building in Toronto. There's a heap of telescopes in the middle of the archive, and the Society's wonderful archivist explained to me that all of them, in various ways, tell the history of astronomy in Canada. He hopes to mount them in a museum - and indeed I drooled over some fascinating pieces. One I found particularly striking: a beautifully-preserved little telescope - is it 40, maybe 50mm across? - used by satellite-trackers in Operation Moonwatch, amid the paranoia that accompanied the early Space Age. The mechanical quality really impressed me - the tabletop tripod alone was a diminutive masterpiece - and I wondered what the optics could reveal. I'll bet today's amateurs would pay through the nose for a travel scope like this one. I visited the archive to look over some astronomical logbooks, and as usual those were a treat. It can be viscerally moving to read over another amateur's drawings and reflections from decades or centuries ago. Our world has changed - and sometimes other worlds have, too - but there's a common thread: the long-dead observer and I both gazed with wonder at something that's far bigger than our fleeting lives. We struggle to put in words what it means for us, as we obsess over equipment and traces of detail in planetary disks. We are the Universe, conscious of itself - but only briefly. The planets are rising high above the early morning horizon, and for once the forecast called for good seeing. I slept fitfully until 4:15 AM, nearly convinced myself to fall back asleep, and finally slipped out the back door at 4:45. I soon found that I couldn't see a planet from my backyard, but I did find a spot nearby where a gap in the trees revealed two brilliant planets. They were remarkably close together - not much more than Jupiter and Venus were about a month ago. With the Sun beginning to brighten the morning sky, I set up my Takahashi and targeted the brightest of those planets. At first, I thought it must be Venus - that's how bright it was - and I assumed the less brilliant, yellowish planet was Jupiter. For a minute or two I thought my finderscope must be misaligned. I kept targeting the brightest planet, and time and again Jupiter showed up in the eyepiece. Finally, it dawned on me - a little later than it might have, had I had more sleep - that in fact the brilliant planet was Jupiter. I was astonished to find that the dimmer - but still very bright - planet was Mars. It's so much brighter now than it was just a month ago - and that, of course, means that it's fast approaching Earth. I was a little disappointed upon observing Jupiter. Towards the eastern horizon, the seeing was a little worse than I'd expected, and although I could make out many salmon-colored belts, shimmering in the tremulous atmosphere, the planet seemed a little washed out. It lacked the vivid reds and ochres that sometimes create such striking contrast on Jupiter. At just over 200x the Galilean moons were tiny disks, but without obvious differences in color. Mars, by contrast, was a deeper red than I've normally seen it. For the first time in two years, I made out a polar icecap - this one the southern icecap - and a dark ring around it that was, in the late nineteenth century, widely assumed to be meltwater lake draining off the cap. I could also discern dark streaks shooting up towards the Martian equator. In the nineteenth century, many astronomers - not just Percival Lowell - figured that these were canals and oases channelling polar meltwater towards cultivated fields. That was how the Martians were thought to cling to life on a drying and cooling world.

Mars is my favorite planet to observe when it nears its biannual opposition (and it's free of planet-encircling dust storms). This morning reminded me of the morning of June 9th, 2020, when I observed Mars for the first time through my FC-100DC, as it began to approach Earth that year. That morning, I was stunned to discern the southern icecap for the first time, along with dark albedo features that had never been visible to me before. It excited me to no end to realize how much more could be visible as the planet wheeled closer and closer to Earth that fall. I have much the same feeling now. I truly can't wait to see what Mars will bring this year. I wonder what I'll be able to glimpse with telescopes that are a little better than those I had in 2020. We've had plenty of clear skies lately - after a generally rainy spring - but the atmosphere has been so turbulent that I've rarely thought it worthwhile to take out a telescope. This week brought more of the same, but also something unique: a rare, close conjunction of Venus and Jupiter in the early morning sky. With the sky mostly clear, transparency quite good, and seeing a good deal worse than average, I woke up at around 5 AM last night and walked out with my Takahashi. I wasn't sure where to go. Trees blocked the view of the planets from my backyard. Before our move, I might have walked to the park I like best, but that's 20 minutes away now. By the time I got there I figured the Sun would be too high in the sky - and I'd be painfully sore from carrying everything. I wandered in that general direction all the same, and then noticed a hill I usually pass while taking my kids to the playground. I decided to walk up the hill just in case - and, sure enough, by the time I got to the top I noticed two brilliant beacons just rising into view above the eastern horizon. Jupiter and Venus! What a difference the new carbon fiber tripod makes! Walking with it is so much easier, and the FC-100DZ is much more stable now. After setting up I plugged in a 24mm Panoptic eyepiece - for a magnification of 33x - and took in the view. I'm not a big conjunction guy - I care much more about seeing details on other worlds than I do about seeing those worlds appear close together - but it was pretty impressive to see both Jupiter and Venus in the same field of view. Although seeing was very poor and it was hard to make out much detail on either world, it was easy to get a sense of just how different they are from each other, and how diverse even our little Solar System really is. It certainly helped that three of Jupiter's moons were clearly visible, and that Venus was roughly halfway illuminated. I tried to take a customary blurry cellphone picture, and just by chance at that very moment a plane zipped in front of Jupiter. As night turned to day, I packed up and walked home. When I returned to my backyard, I noticed that Jupiter and Venus were both clearly visible from a little spot near my fence. Maybe I hadn't needed to walk, after all? Still, there's always something magical about that hour before sunrise, when the city is still asleep and the loudest noises are often birdsong.

|

Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed